Concerned about an onslaught of enfeebled old people? Don’t worry, robots will take care of them! American techno-optimism knows no bounds, and so-called “age-independence” technologies are proliferating like crazy. But in a profoundly ageist culture, the implications can be disturbing. Here’s a critique of the latest article to catch my eye, “As Aging Population Grows, So Do Robotic Health Aides,” which appeared in the New York Times on December 4, 2015.

Let’s start with the hand-wringing opener [emphasis mine]: “The ranks of older and frail adults are growing rapidly in the developed world, raising alarms about how society is going to help them take care of themselves.” Frailty is indeed the biggest threat to an active old age, although only a subset of olders are at risk. It’s also easily detectable and the most remediable. Even very old people who are already frail see huge gains from modest interventions, like walking more or doing simple weight training exercises.

Next up, the inevitable alarm about global wrinkling: “An aging population will place enormous burdens on the world’s health care system by 2050.” In fact, older people are not inevitable money pits for health dollars. People aren’t just living longer; they’re healthier and are disabled for fewer years of their lives than older people of decades ago. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, the share of US health care spending going toward nursing and retirement homes has declined since 2000 and been flat since 2006. The ten-year MacArthur Foundation Study of Aging in America concluded that once people reach sixty-five, their added years don’t have a major impact on Medicare costs. People over eighty actually cost less to care for at the end of life than people in their sixties and seventies. It’s high-tech interventions, not older patients, that make modern medicine so expensive.

On to another bit of problematic language: “Despite a patchwork of research and some commercial products, the United States appears to be lagging Japan and Europe in developing solutions.” Solutions to what? Aging is a natural, lifelong process, not a problem to be solved. Longevity is a fundamental hallmark of human progress.

Population aging—the prospect of many more of us living into our 80s and 90s— does mean that people will require more assistance of various kinds. Technology can indeed help us address some of these legitimate challenges.

- Problem: limited mobility. Solution: small autonomous drones that will carry out household tasks, like reaching under a table to grab an object, fetching something from the other room, and cleaning. This sounds nifty. Please, though, do not call mine a “Bibbidi Bobbidi Bot,” as University of Illinois robotocist Naira Hovakimyan has dubbed the prototypes to make them less intimidating. I can handle “drone.” Even people with severe Alzheimer’s have been shown to react aggressively to infantilizing language.

- Problem: “wandering.” Solution: smart pendants that track location. That makes sense.

- Problem: tracking health status. Solution: “room and home sensors” that presumably verify that you’re up and around and have opened the fridge; devices with screens for video conferencing with health care providers. Those, too, make sense, and many more healthcare-related technologies are in the works.

- Problem: driving. Solution: “Driver assistance [that] will turn cars into elder-care robots.” This is a great freakin’ idea. Google’s driverless cars are safer than human-operated vehicles, and Americans who can’t drive are hostage to lousy alternatives or homebound.

These benefits are real, but they’re limited. Technology, as we should know by now, is no panacea for complex social problems. Looking for ways to profit from the fast-growing “silver market,” thousands of companies are pitching devices as a solution not only for mobility and wellness issues but to remediate loneliness and isolation. “In addition to smart-home sensors and mobile robots,” the article continues, “there are a variety of other efforts to add stationary robots to provide everything from coaching to communications to companionship.”

Communications, absolutely. Skype, Facetime and other web-based technologies are terrific ways to help people of all ages stay connected. Coaching, why not? Lots of learning involves the kinds of drills and repetition that machines are made for. I can envision some kind of gym droid making me stretch and sweat and work on my balance. I’d name it and curse it and grow attached to it, and probably do the same for the drone carrying my shopping bag and the bot beating me at Boggle.

But that’s not companionship. Facetime is not the same as being together. A robot is not the same as a friend. I’m willing to bet that even people with advanced dementia can tell the difference, and I’m not surprised by the response of a 91-year-old woman to “an Internet-connected tabletop robot with a round swiveling screen that portrays a friendly robotic face” called Jibo. “If Jibo were my last friend,” she said, “I would be very depressed.” Danger, Will Robinson, danger!

As advertised, all these assistive technologies will help people stay in their own homes longer. That’s a priority for many and a boon for the insurance industry, because “aging in place” is cheaper than institutionalization. But they are no remedy for the “epidemic levels” of loneliness that an executive at Brookdale Senior Living describes in the article. Just the opposite, in fact, because staying at home all too often means ending up alone.

Sure, machines could be trained to do a great job. The presence of a sophisticated, infinitely patient robot designed to show pictures of your kids or play Scrabble or drive you to the movies might arguably be better than that of a human trained only to keep you safe, whose thoughts are likely on the faraway children her minimum wage supports. Those marvelous robots will inevitably serve the wealthiest consumers, however, widening the inequality gap and distracting us from the kinds of communitarian solutions that will help us all.

The fact that many people end up lonely and isolated is not inherent to growing old. It reflects some regrettable—and very American—priorities:

- We don’t value caregiving, work largely performed by women who are unpaid or underpaid.

- We idealize self-reliance. This downplays life’s challenges, and shames us when, inevitably, we fall short.

- We value youth over age. Internalized ageism makes people reluctant to adopt technologies that might telegraph vulnerability. At the other end of the spectrum, technophiles embrace “anti-aging” biotechnologies in the hopes of transcending senescence and even mortality. The denial is collective as well. It’s why the US is so ill-prepared for a demographic transition that’s been on the horizon since the 1950s.

Neither the “problem” nor the “solution” is technological. It is social.

Humans are social animals, and we’re meant to live in community. Social connections give life meaning, and are key to a happy and healthy old age. Instead of focusing on devices that reduce the need for human contact, why not make the most of our human resources?We already have something really good at looking after humans: other humans. Millions of people are out of work and a caregiver crisis is growing more acute.

If we genuinely care about well-being in late life, we need to create opportunities for older people to come together with people of all ages, ways to get there, and meaningful activities to engage in, from the mundane to the metaphysical. Older members of society are uniquely qualified to be watchdogs, advocates, educators and futurists. Not to mention backwards-understanders; as Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard observed, “Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.”

Our drones can come along.

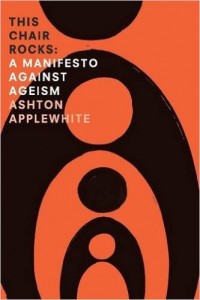

Ashton Applewhite began blogging about aging and ageism in 2007 and started speaking on the subject in July, 2012, which is also when she started the Yo, Is This Ageist? blog. Her book, This Chair Rocks: A Manifesto Against Ageism, was published in March, 2016. This column is reposted from Ashton’s blog.

Comments