A briefing paper prepared for the Council on Contemporary Families Online Symposium on Gender and Millennials, originally released March 31, 2017.

In this study, I use the National Exit Poll and Tisch College/CIRCLE’s nationally representative tracking poll of Millennials to explore how young men and women differed in their vote choice in 2016, how they chose their candidates, and how they seem to be responding to the outcome of the election.

When it comes to voting, youths are politically more liberal than older age groups, and young women more liberal than young men. Yet although young adults aged 18 to 29 were more likely to support Clinton in 2016 than any other age group (55 percent overall), youth support overall for Democratic candidates has declined since 2008 and 2012. As I explain below, this was largely due to shifts in the allegiances of politically moderate young men and to the increased representation, and likely rising turnout, of the strongest Trump-supporter group among youth: White men without a college degree.

Reflecting the gender difference in vote choice, Millennial men and women have different views of the new Trump Administration and what risks and opportunities it presents. Women are overall much less optimistic, and more worried about people’s rights. Yet they do not report feeling motivated to become more involved in politics. Therefore, even though Millennial women perceive biases and injustice against women connected to the rise of this new administration, they may not choose to address these issues by becoming politically involved.

On the other hand, historical analysis suggests that young people’s commitment to equality rises during Republican administrations, something that was certainly the case during the George W. Bush Administration. If this pattern applies, we may see a significant rise in youth civic and political engagement in the near future.

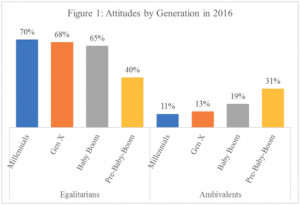

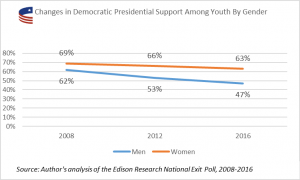

Youth Vote 2008-2016: Men and Women, Once United, Now Divided. In 2016, Hillary Clinton won 55 percent of voters under age 30, a higher percentage than any other age group. Despite the decisive youth support for Mrs. Clinton, her victory among this group was much lower than that of Barack Obama. In 2008, 66 percent of all youth voted for the Democratic candidate, and a solid 60 percent did so in 2012.

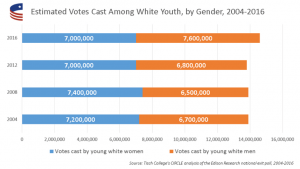

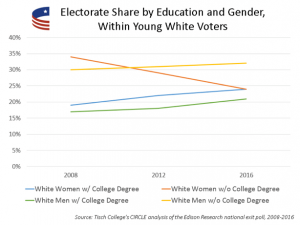

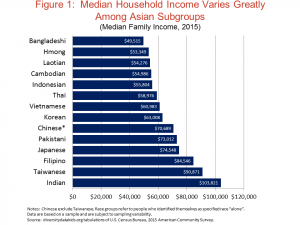

The gender differences in youth support for candidates were larger than in other recent elections. Almost two-thirds (63 percent) of young female voters supported Hillary Clinton, compared to slightly less than half (47 percent) of young men (see Figure 1). There was also a significant reversal in the turnout of young men and women. In 2004, 2008, and 2012, more young White women voted than did young White men. But in 2016 the opposite was true. While the turnout of young White women remained fairly stable through the last four Presidential elections, 2016 saw the greatest number of votes cast by young White men in the past 12 years — markedly higher than their female counterparts (see Figure 2).

Figure 1

Figure 2

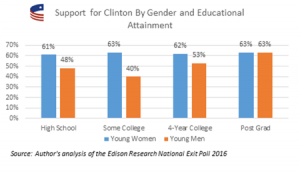

The gender difference in support for Hillary Clinton was largest among youth who had attended college at one point but did not have a degree (see Figure 3). This group includes many current college students along with those who have college experience but do not have a four-year degree.

Figure 3

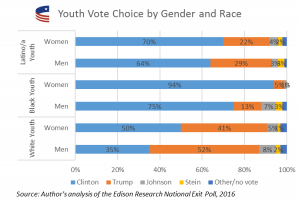

The National Exit Poll also reveals gender differences in support for Hillary Clinton across racial groups. Black and Latina women were more likely to support Hillary Clinton than their male counterparts, often by a substantial margin. But young White men comprised the only youth group that gave majority support to Donald Trump (52 percent for Trump, 35 percent for Clinton). White women were far less likely to vote for Clinton than women of other racial and ethnic backgrounds, but still gave Clinton a 9-point edge over Trump (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

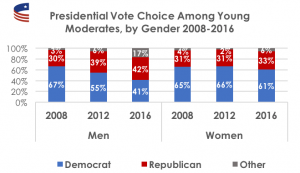

Rapidly declining support for the Democratic presidential candidate from young men who consider themselves political moderates contributed to the overall decline in the proportion of young voters who supported Clinton. In 2008, two-thirds of young moderates, both men and women, supported Barack Obama. But in 2016, just 41 percent of young male moderates voted for Hillary Clinton, even though support from young female moderates fell only modestly, from 65 percent in 2008 to 61 percent in 2016 (see Figure 5).

Figure 5

Shifts in the demographic composition of White youth voters also contributed to the overall decline in youth support for the democratic candidate. As noted above, for many past elections young women’s voter turnout surpassed those of young men’s, and among White youth, women without a college degree made up the largest share in 2008. Since then, the share of young White votes cast by women without college degree has declined steadily, and in 2016, the share of male voters without college degrees far surpassed that of their female counterparts (and of college-educated youth of either sex, see Figure 6). This shift is important because White men without a college degree overwhelmingly supported Donald Trump, by a staggering 31-point margin (see Figure 7).

Additional analyses, available on request, imply (though not conclusively) that among men, a majority of whom had voted for Obama in 2008 regardless of race, many had become increasingly disillusioned by 2012, and were driven toward Trump in 2016. Young men who had voted in a presidential election before 2016 were far more likely to vote for Trump than the first-time voting men, by a large margin. Vote choice among young women did not differ by previous voting experience.

Figure 6

Figure 7

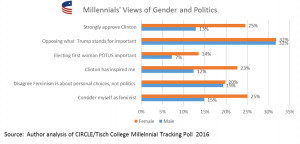

Many Millennials, But Not All, Thought Gender Played a Role This Election. Compared to past cohorts of women, Millennials face relatively few structural and explicit gender barriers. But during the 2016 campaign, 33 percent of Millennial women perceived clear gender biases against Hillary Clinton in the media, while 30 percent of young men thought that the media was biased in Clinton’s favor. About one month after the election, Millennial men and women were somewhat divided on how they saw the new Trump administration and whether women have the same access to opportunities as men do today. Only one-third of Millennial women considered Donald Trump their president, compared to 44 percent of Millennial men, and also only one-third (34 percent) of Millennial women believed that men and women now had the same opportunities, while half (48 percent) of their male counter-parts thought so (see Figure 8).

Figure 8

For Millennials, Feminism is Personal, but Not Political. Although women were more likely to think that Hillary Clinton’s gender influenced the election in some ways, data also show that Millennials, including women, tend not to connect gender and politics. Only a quarter of women (and 15 percent of men) in this age group consider themselves feminists. Furthermore, only 20 percent disagree with the statement “Feminism is about personal choice, not politics.” Indeed, just 14 percent of Millennial women said that electing the first female President of the United States was an important factor in their candidate choice (See Figure 9).

Figure 9

Will Millennial Men and Women Stay Equally Involved in Civic Life in the Future? In short, Millennial men and women are not engaged in the same way and at the same level. Millennial women, generally speaking, are more likely to volunteer and to vote, whereas Millennial men are more likely to aspire to elected office, consume political news, especially through late-night news comedy shows, and discuss political issues with their peers. Although patterns of individual civic engagement are complex and should not be oversimplified, Millennial women tend to contribute to civic life by supporting civil society (including at local and national elections), while men are more comfortable with political involvement.

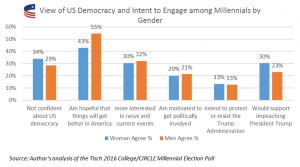

But will their engagement levels and patterns stay the same after the unusual election of the 2016? Young men and women differ in their view of the health of U.S. democracy, with men feeling more hopeful than women. However, this does not seem to lead them to report different levels of intent to engage in politics in the near future (see Figure 10). As found in the recent study from CIRCLE, Clinton voters reported being far more motivated to engage in politics, especially to resist the new Trump administration, than Trump voters. Yet the relative lack of difference between men and women in this analysis indicates that although Millennial women felt less hopeful about U.S. democracy under the Trump administration, they were not yet motivated to take political action shortly after the election. It is worth noting, however, that this polling occurred before the inauguration and the Women’s marches that occurred across the country the following day. According to several national polls taken in the second half of February, Trump’s disapproval ratings have increased since then. It is possible that Millennial women may become increasingly willing to engage in politics.

Figure 10

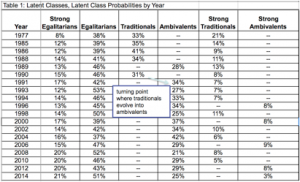

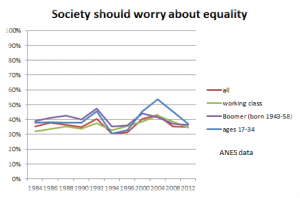

There is, moreover, some indication that young people, regardless of gender, may become more engaged throughout the current administration. My colleague Peter Levine analyzed the American National Election Survey data from 1984 to the present and found that overall, people’s concerns about equality rises during Republican administration and subsides during Democratic administrations (see Figure 11). This was most pronounced in the George W. Bush and Barack Obama administrations. It is then reasonable to expect that more young people will become politically engaged in the coming years.

Figure 11

© Peter Levine, 2017: http://peterlevine.ws/?p=18064

Conclusion. This gender-centered view into the 2016 presidential election data highlights the complexity and diversity of the Millennial generation, which simply cannot be described as a monolith who hold the same values, believe in the same things, and — especially when it comes to voting — lean Democratic. The data tells a story of a generation once united by the rhetoric of “hope and change” in President Obama’s campaign, and solidified by the belief in equality, but now deeply divided and consequently conflicted over who to blame for their disappointment.

The Pepin and Cotter brief may seem at odds with this paper because it points to an important decline in gender egalitarianism, which is alarming because, if true and enduring, our country could be pedaling back from decades of progress toward gender equity. On the other hand, our data suggest that the large shifts in attitudes and behaviors occurred among a specific demographic group, namely men, and most especially White men without a college degree, a conclusion supported by Fate-Dickson’s analysis of the GSS findings. As Pepin and Cotter point out, it is possible that “a significant minority of youths have reverted to an endorsement of male supremacy, at least within the family realm” but certainly not all.

That said, the data from Tisch College’s CIRCLE Millennial poll also indicates that relatively few Millennial women explicitly identify as feminists (25 percent) and even fewer men (15 percent) see themselves as such, despite the rise in the number of “stay-at-home dads” noted by Van Bavel. This may seem like a conundrum to seasoned feminists who have long argued that “the personal is political.” But, only one-fifth of Millennials regard feminism as a political rather than just a personal stance. In fact, even among women, just 14 percent named electing the first female President of the United States as an important factor in their vote choice.

Many if not most Millennials believe that men and women should have equal access to opportunities and power in general, a trend that’s likely to increase according to their historic patterns. But, as Pepin and Cotter point out, some now believe that in their families, it is okay for men to have more power, and that personal choices about gender relationships at home have no bearing on what will happen to the egalitarian political and work opportunities they seem to support. One strategy may be to strengthen civic and community education to help young people understand how their personal choices and decisions are influenced by, and have impact on, our public policies.

Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg is the director of CIRCLE Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life at Tufts University.

This fact sheet was compiled for the Council on Contemporary Families by scholars at

This fact sheet was compiled for the Council on Contemporary Families by scholars at

The Council on Contemporary Families Gender and Millennials Online Symposium presents research on how Millennial men and women are changing—and how they are not changing. Countering the recent trend of ignoring inconvenient facts, this symposium makes it clear that attitudes about gender equality are more complex than either supporters or opponents of feminism often admit. Here’s a quick review of the brief reports.

The Council on Contemporary Families Gender and Millennials Online Symposium presents research on how Millennial men and women are changing—and how they are not changing. Countering the recent trend of ignoring inconvenient facts, this symposium makes it clear that attitudes about gender equality are more complex than either supporters or opponents of feminism often admit. Here’s a quick review of the brief reports. Look on Pinterest, on the front page of the newspaper, and even in our own hands as we scroll through social media feeds on our smartphones: the importance of our home objects is everywhere. I see bestselling books about how to make getting rid of our things (category by category, that is – preferably starting with those seven extra crates of shoes)

Look on Pinterest, on the front page of the newspaper, and even in our own hands as we scroll through social media feeds on our smartphones: the importance of our home objects is everywhere. I see bestselling books about how to make getting rid of our things (category by category, that is – preferably starting with those seven extra crates of shoes)