One of the most robust findings in industrialized societies is that children no longer confer an advantage in life satisfaction or happiness to their parents relative to those who do not have children. While the extent of the gap varies by country, life stage, and other characteristics of parents, there does not seem to be a time or place where parenthood positively affects well-being after industrialization strips children of their direct economic value to parents (and creates long periods of dependency and educational spending instead).

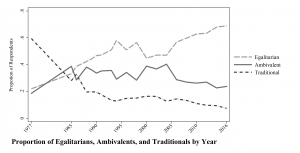

In a 2016 study, authors Chris Herbst and John Ifcher show a different trend, however. Using U.S. data over the past 30 years and comparing parents actively parenting children under 18 in their household to those without children in their household, they show this happiness gap slowly closing and disappearing completely after 1997. They discussed these findings in a 2017 blog post for the Institute for Family Studies, believing that the gap has closed because non-parents have become increasingly vulnerable to loneliness, social distrust, and economic insecurity.

Looking carefully at their analysis, however, it seems like a different story could also be told. First, Herbst and Ifcher exclude two important categories of parents whose prevalence and distress have presumably grown over time: non-custodial parents and parents of children over 17. These groups are instead considered “non-parents” in the Herbst and Ifcher trend analysis. Non-custodial parents as a percentage of all biological parents have increased since 1986, and research shows this group of parents to be particularly distressed (see Simon and Caputo), since separation or divorce decrease daily contact with their children and increase expenses for non-custodial parents. While single parents are more distressed than married parents, non-custodial parents are more distressed than both groups.

Parents of children over 18 have also both grown as a proportion of all parents since 1986 and seen both their financial and care obligations for their adult children increase over this period. Indeed, developmental scientists now speak about “emerging adulthood” to describe this post-18 to late twenties period of time in which young people are still partially dependent upon their parents for support and guidance. Paying for college has become a major burden for many parents of emerging adults, while the proportion still living with their parents or moving in and out of their parents’ household has grown to post-war highs. The number of young adults with developmental disorders (autism spectrum or ADHD diagnoses) has also increased over time. As the ACA has acknowledged this dependency by allowing young adults to stay on their parents’ health insurance until age 26, so too must data analysts wanting to understand contemporary parenting and its financial and social stressors. While most analyses find that so-called “empty-nest” parents are happier than parents actively parenting younger children, fewer and fewer parents of children over 18 actually have an empty nest!

When these two groups are combined with respondents who have never had children, they easily swamp the truly child-free in analyses of parental happiness. After all, about 80% of people in the U.S. still eventually have children, and those children will eventually turn 18. So comparing parents of children 17 and younger to everyone else really confounds parenthood with life stage and marital status. Rather than seeing the parental happiness gap converging and disappearing post 1997, what may really be going on is a shift in the responsibilities of parenting both spilling out across non-married households and extending into young adulthood, pulling down the happiness of those mistakenly categorized as “child-free.”

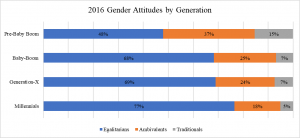

Second, the Herbst and Ifcher analysis does not explicitly consider the fall in fertility and increasing selectivity of parenting. While still high in comparative perspective, teen and unplanned pregnancies have been declining in the U.S. since 1997, and overall fertility rates have declined in all racial and ethnic groups. Some of that decline has been involuntary — some adults may feel “freer” to not become parents because they cannot find suitable partners, have inadequate or unstable incomes, or jobs that demand too many hours to consider adding children to their lives. These are not exogenous forces affecting fertility– they are in themselves endogenous to social forces that have made the stressors of parenting increase over time to the point that many young adults sadly forego parenthood.

Herbst and Ifcher’s trend analysis is consistent with this explanation. First, they do not find that parental happiness is actually increasing over time. Rather parental happiness has been constant over time while those they characterize as non-parents have become less happy over time. If parenthood is becoming more selective yet happiness is not increasing, this in itself demonstrates that contemporary parenting of minor children has become increasingly stressful over time. And if “non-parents” increasingly consist of non-custodial parents financially supporting minor children, older parents still supporting adult children, and involuntarily childless people unable to find the partners or jobs that would accommodate their desires for parenthood, it’s not surprising that non-parents’ unhappiness has grown over time.

However, none of their findings comport with the belief that children protect parents against loneliness, social isolation, or financial distress. If anything, the trend over time suggests that the forces that reduce happiness among parents of minor children now extend beyond that group to non-custodial parents, “empty-nest” parents, and involuntarily child-free adults. Herbst concludes, correctly, that his results are probably affected by these factors: “…we cannot discount the possibility that compositional shifts among parents and non-parents have driven the change in parental happiness.”

What seems clear across studies is that contemporary industrialized societies are struggling to avoid below replacement fertility, and understand how to integrate production and reproduction in a way that respects the sacrifices that parents are routinely expected to undertake to raise healthy educated citizens. When the costs of children are privatized but the benefits are socialized, we see a parental happiness penalty that persists across a wide variety of contexts and circumstances, as well as increasing selectivity in who becomes parents. The challenge is to create public support systems that encourage responsible parenthood among those who want to become parents without coercing those who do not. Ending the extraordinary financial and opportunity costs of parenthood is certainly a good place to start.

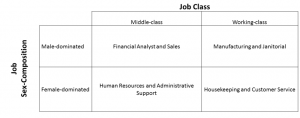

Jennifer Glass is Centennial Commission Professor in the Department of Sociology and Population Research Center of the University of Texas, Austin. Her most recent projects explore whether governmental work-family policies improve parents’ and children’s health and well-being, whether women’s jobs really have better work-family amenities than men’s, why women’s retention in STEM occupations remains so low, and how the economic costs of motherhood have changed over time.