Talking with your children about sex is important in setting them up for healthy sexual development, but it’s also really hard work! It can be difficult to know what information your children need from you if you’re not sure where they are at with their own sexual feelings, behaviors, and concerns. You may wonder: “Is my child sexually active or just spending romantic time with her girlfriend?” or “Does my child have questions or insecurities about their body I’m not aware of?” or “Is the information I’ve provided my child enough for where he’s at in his development?”

This is where our research comes in! We wanted to know if how often parents talked with teens about sex, and how open they were during these conversations was related to how much the child would open up to parents about their sexual feelings, concerns, and behaviors. We wanted to know so we could provide tips for parents on how to potentially help their child feel like they can open up about these topics.

Our Study

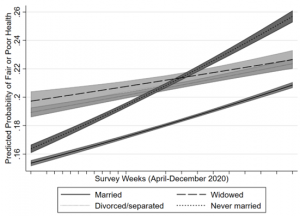

We surveyed 603 pairs of mothers and their teenage children ages 12-17. We asked each of them questions about how often they talk about sex-related topics together (frequency) and the level of communication openness of these conversations (openness). More open conversations were more comfortable, interactive, honest, and involved the mother actively listening to the teenage child. We also asked about how often the teenager deliberately told their mom about their sexual feelings, concerns, and behaviors (disclosure) and how often they kept secrets related to sex from their mom (secret keeping).

Our analysis showed that:

- Teens who talked with moms more often about sex-related topics were more likely to disclose to mothers about sex, BUT were also more likely to keep secrets from moms about sex.

- Teens who talked with moms more with a more open communication style were more likely to disclose to mothers about sex AND were also less likely to keep secrets from moms about sex.

- When communication about sex-related topics was BOTH frequent AND open, teens were more likely to disclose to mothers about sex AND were also less likely to keep secrets from moms about sex.

What Does It Mean?

Our findings show that how often you talk with teens about sex and how open you are during these talks are both important.

Talking frequently in a way that is not open (e.g., lecturing, not respecting the child’s point of view) may create more conversational opportunities for a child to answer questions, but it may also send negative messages to the child. If parents are constantly lecturing to their children or sending messages that children don’t agree with, children will likely feel unable to disclose certain information about their beliefs, identity, or experiences to parents. For example, a child who is constantly lectured that sex is only okay in marriage may be unlikely to tell their parents if they are sexually active or if they’ve experienced sexual violence, even when they need support.

This is why openness during parent-child talks about sex-related topics is so important! As shown in our analysis, if these conversations were frequent AND open, children shared more with their mothers. Even if parents are talking with their child about sexuality regularly, if these conversations are one-sided, parent-dominated, and discouraging or dismissive of child input or perspectives (typical of most parent-child conversations about sex), this may further cement the message that parents do not want to hear about the child’s true experiences and feelings. Children may not feel safe, comfortable, or able to share secrets related to sexuality.

Start Having Open Conversations with Your Child Today!

If you want to set up a foundation for your child to share with you about their sexual concerns, feelings, and behaviors, you can start today by having open conversations about sex-related topics with your child- no matter what age! Visit my favorite resource Sex Positive Families for tips on how to get started. Parents can be extremely influential in positively influencing their child’s sexual development, so I encourage you to start today!

Shelby Astle, MS, CFLE is a Ph.D candidate in Applied Family Science at Kansas State University. Her research interests include parent-child sexual communication and sexual self-concept. The ultimate goal of her work is to improve young people’s sexual well-being by improving how they are socialized around sex-related topics. You can follow her research on Twitter @astleshelby and LinkedIn

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/I4KRIKP4P5FRBD7FMHK4FEVSBU.jpg)