The expansion of contraception over the last several decades has made it possible for more people to avoid having a child, or another child, when they don’t want one.

But, contraceptive access is far from universal, and contraceptives—and the humans who use them—aren’t perfect, so unintended pregnancies still make up almost half of all pregnancies worldwide. Barriers to abortion—in many parts of the world, strict legal barriers—mean that pregnant people have no option but to keep the pregnancy.

So, what happens when someone becomes pregnant unintentionally and must carry it to term? Does it harm their health? It’s a surprisingly tricky question to answer in a scientifically sound way because it takes both a significant amount of time and specific types of data that are not typically collected. Given these constraints, a few studies have tried creative approaches; for example, one compared the health of women who were denied an abortion in the U.S. to that of women who were able to obtain one just under the gestational limit.

Rather than focus on the extreme case of carrying a pregnancy after having sought an abortion, we opted to study a general population of women to develop a broader sense of the implications of unintended pregnancies for those who give birth. This allowed us to study not only the diverse group of women who had an unintended birth, but also women who had an intended birth, as well as the many women who were able to avoid getting pregnant all together.

We focused our study on Malawi, a country in southeastern Africa where fertility is high and abortion is heavily restricted. We followed women ages 15 to 25 over six years, interviewing them frequently about their fertility desires, offering them pregnancy tests, and studying their health over time.

What did we find? Unintended pregnancies were common among women in our study. Importantly, and consistent with other research, not all women responded negatively to these pregnancies. When we asked women how they felt about their unintended pregnancy soon after they learned of it, we found that although many women were distressed, others were okay—and even happy—with the unexpected outcome.

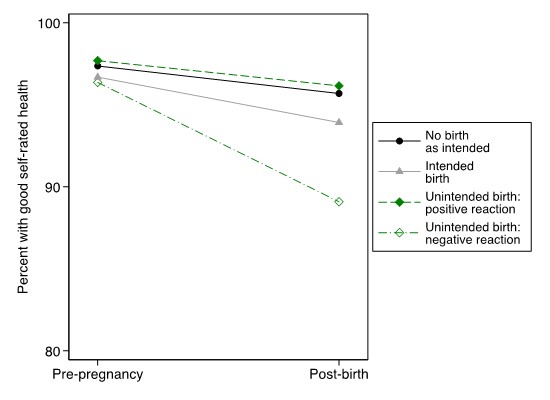

Women’s distinct responses to their unintended pregnancies proved to be more than just offhand reactions. Negative feelings helped distinguish the women whose health declined in the 3 to 5 years after they gave birth. But what about the women who had a positive reaction to the pregnancy? These women didn’t fare any worse than comparison groups (see Figure).

Encouragingly, our study suggests that—even in a part of the world with high maternal morbidity and widespread poverty—certain unintended births are not harmful for women’s health. Women who welcome an unintended pregnancy exhibit resiliency and the ability to cope with the unanticipated development.

Also good news is that asking people how they feel about their unintended pregnancy is a simple piece of information that clinicians can easily collect and use in their efforts to counsel pregnant women on their options going forward. For those who feel bad about an unintended pregnancy, ensuring they have the option to terminate their pregnancy would allow them to protect their own health, and by extension, their family’s health. Unfortunately, many people around the globe, as well as increasing numbers in the U.S., lack access to safe and accessible abortion care, meaning that they will have little choice but to continue the unintended pregnancies that are most likely to do them harm.

Finally, when women continue their pregnancies—whether through choice or necessity—healthcare professionals should also ask them their feelings about the pregnancy in pre- and post-natal care. These feelings are important harbingers of the pregnancy’s consequences and, when necessary, should trigger additional counseling and resources to support women and their children.

Acknowledgements: This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R03-HD097360, R01-HD058366, R01-HD077873) and by the NICHD-funded University of Colorado Population Center (P2C HD066613).

Sara Yeatman (sara.yeatman@ucdenver.edu) is Professor of Health and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Colorado Denver. She researches the causes and consequences of unintended fertility in the United States and Malawi. You can find them at Twitter @sarayeatman

Emily Smith-Greenaway (smithgre@usc.edu) is Associate Professor of Sociology and Spatial Sciences at the University of Southern California. Her research centers on understanding social and health inequality. You can find them on Twitter @smithgreenaway

Comments 4

Christen Waste — November 21, 2021

Thankfully, our research shows that even in areas of high maternal mortality and widespread poverty, some unwanted pregnancies are not hazardous to women's health. Women who accept an unwanted pregnancy show resilience and adaptability. The good news is that professionals can simply gather and utilize this information to guide pregnant women on their choices moving forward. Those who regret an unexpected pregnancy may preserve their own and, by extension, their family's health by having the choice to terminate the pregnancy.

Hemp Skin Care

Arron — April 11, 2022

I really appreciated for the best type of article, knowing about pregnant women experiences that they tried to have for the rest of their lives. affordablelectricians.com.au/electrician-noosa.html

Ronald — April 12, 2022

I am truly proud in any women that turns into pregnancies just because on how to care for their babies, thanks for sharing best info updates of the blog that looks very impressive. Electrician croydon

Mark — August 11, 2022

what a best information in the best type of article sharing beautiful post that makes me amazed all about pregnancies. thanks! Julian