Move-in day at four-year residential colleges and universities around the U.S. marks a parenting milestone. But what happens next? Although most parents of college students do not have an embodied presence on their child’s dormitory floor, some provide so much financial, emotional, and logistical support that it seems they never left.

Move-in day at four-year residential colleges and universities around the U.S. marks a parenting milestone. But what happens next? Although most parents of college students do not have an embodied presence on their child’s dormitory floor, some provide so much financial, emotional, and logistical support that it seems they never left.

The media refers to these parents as “helicopters” and they are among the most reviled figures of 21st century parenting (see this recent Washington Post article for an example). They are derided as pesky interlopers in the postsecondary system, who unnecessarily intervene with university programming, test the patience of college officials, and create needy students. Because intensive parenting is a task that falls mostly on the shoulders of women, many critiques also have a mother-blaming bent.

Do involved parents burden the university? In Parenting to a Degree: How Family Matters for College Women’s Success, I followed 41 families as their children moved through a public flagship university between the years of 2004 and 2009. I conducted a year of ethnographic observation in a women’s residence hall, interviewed both mothers and fathers, and conducted five years of annual interviews with their daughters.

The university I studied, like many other public schools, lacked the deep pockets and rich resources of elite privates. Rather than evading helicopters, the school actively cultivated a partnership with involved parents. Out-of-state parents were considered a real asset, as they were typically both affluent and well-educated. In the face of steep state budget cuts and mounting accountability pressures, the institution relied on parents to fill numerous financial, advisory, and support functions. It is not unique in adopting such a strategy.

Net tuition now rivals state and local appropriations as the primary funder of public higher education. In this equation, parents become a crucial source of funds. Four-year schools also structure their classes, activities, and living options around traditional students and expect parents to do the work of maintaining them. Many parents in the middle to top stratum of the class structure readily accept these tasks. They have come to believe that a college experience is something that “good” parents offer, no matter the cost.

The sheer diversity of academic and social options on today’s college campuses means that there are many ways for students make costly mistakes. Yet, as advisor to student ratios steadily rise, tailored advice is typically not coming from public university staff. Students are expected to seek guidance from home. Affluent, well-educated parents—typically mothers—dive headlong into the roles of academic advisor, career counselor, therapist, and life coach. They have flexible careers that allow for emergency visits, a savvy understanding of higher education, the ability to interface with university staff, and money to smooth over every hurdle.

Parents even help translate college degrees into jobs. Elite companies look for markers of status that parents cultivate in their children—for example, skill in upper-class extracurricular activities, a narrative of self-actualization, and delicately honed interactional skills. Universities rely on families to embed these traits, as the degree alone is not enough to get a good job. Internship and job placement services are also outsourced to parents, who craft resumes, tap their networks for opportunities, and enable moves to urban locations.

This arrangement takes a toll on all families. Adults extend parenting responsibilities further into their own life course, undermining their own financial security and draining emotional and psychological reserves. There is also some truth to the notion that the helicoptered children are slow to adapt to adulthood; their academic success can come at the cost of self-development in other spheres.

But families of modest means stand to lose the most ground. University outsourcing to parents increases the salience of family background for academic and career success, exacerbating existing inequities. Well-resourced parents are advantaged when parental labor is built into the very form and function of the university. They can out-fund, out-strategize, and out-network the competition. In contrast, less privileged parents are reliant on what the university offers. They are often deeply disappointed.

The helicopter parent blame game distorts the real issue: Public universities are growing dependent on private family resources for their existence. As parents become more central to the operation of higher education, the social mobility mission of the mid-20th century public university gradually slips away.

Laura T. Hamilton is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Merced. Hamilton’s new book, Parenting to a Degree: How Family Matters for College and Beyond, was recently released by the University of Chicago Press. In this book, Hamilton vividly captures the parenting approaches of mothers and fathers as their daughters move through Midwest U and into the workforce.

For all of its craziness and scariness, the 2016 election campaign has hammered home for millions of Americans the degree to which

For all of its craziness and scariness, the 2016 election campaign has hammered home for millions of Americans the degree to which  The latest edition of Stephanie Coontz’s

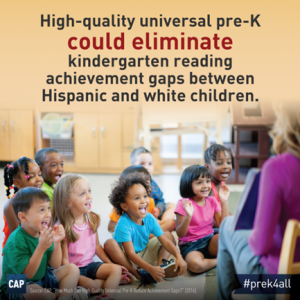

The latest edition of Stephanie Coontz’s  Katherine Gallagher Robbins (@kfgrobbins) is the Director of Family Policy for the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress (CAP). Before joining CAP, Robbins was the director of research and policy analysis at the National Women’s Law Center. Robbins holds a bachelor’s degree in government from the College of William and Mary and a doctorate in political science from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Katherine Gallagher Robbins (@kfgrobbins) is the Director of Family Policy for the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress (CAP). Before joining CAP, Robbins was the director of research and policy analysis at the National Women’s Law Center. Robbins holds a bachelor’s degree in government from the College of William and Mary and a doctorate in political science from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Families at all levels of income are struggling in our economy simply because it does not allow congenial coexistence of work and family life. Lives have become busier and busier and policies have not changed to reflect that. In her book,

Families at all levels of income are struggling in our economy simply because it does not allow congenial coexistence of work and family life. Lives have become busier and busier and policies have not changed to reflect that. In her book,