Terms like “empowerment” have flooded popular culture for quite some time, often in relation to promoting consumerism as well as hypersexual self-presentation. Of late, though, a rather unlikely source employed the word “feminist” to describe herself. Last week, media sensation Miley Cyrus stated: “I’m one of the biggest feminists in the world because I tell women not to be scared of anything.”

Central to Miley’s values of “not being scared of anything” is her embrace of shock value, especially as related to seemingly self-assured hypersexual posturing. As consumers of popular culture are likely familiar, she exhibited her self-confidence at the August 2013 VMAS, in which she performed a raunchy rendition of “Blurred Lines” with Robin Thicke. She continued her domination of the headlines by appearing nude (save for some boots) in the music video for her song “Wrecking Ball.” This sort of “empowerment” has underscored Miley’s rebranding effort from Hannah Montana to…something else more…well, “adult.”

Given that Miley’s brand of feminism feels more like Girls Gone Wild than a feminist figurehead, it’s quite interesting that she uses “feminist” as a self-descriptor. It’s notable, too, since many female celebrities, especially her contemporaries, have distanced themselves from identifying as a feminist. For example:

Katy Perry: “I am not a feminist, but I do believe in the strength of women.”

Carrie Underwood: “I wouldn’t go so far as to say I am a feminist, that can come off as a negative connotation. But I am a strong female.”

Beyoncé: “That word [feminist] can be very extreme … I guess I am a modern-day feminist. I do believe in equality … Why do you have to choose what type of woman you are? Why do you have to label yourself anything? I’m just a woman, and I love being a woman.”

The qualifications in Katy, Carrie, and Beyoncé’s communication about employing the word “feminist” reflects a longstanding conversation in feminist scholarship about why feminist has become a label that is fraught with contention. Part of the reason seems to be the history of generational conflict associated with women’s efforts to fulfill feminist aims. Along these lines, women seem to want to assert that their view of feminism is not that of their mothers or grandmothers. They want to own their feminism.

In addition, female celebrities’ ambivalence towards the term “feminist” is perhaps based on the ways in which notions of feminism have been communicated through mass media outlets over almost fifty years. As many scholars of consumer culture have identified, feminist discourse has been employed in advertisements and other media products to create a positive association between goods and the values we associate with them. This, in turn, has led to a devaluing of the language of feminism in popular culture, particularly in relation to feeling good through self-beautification. So, for instance, even though most people are aware that it’s simplistic to equate an experience of empowerment with nail polish, the constant presence of manufactured visual/verbal associations reinforces the desired meaning of the message, as in this advertisement:

While it is unlikely that wearing a nail polish called “Empowerment” will actually lead a woman to feel empowered when she wears it, it is possible that her act of carving out a space in her busy day to take care of herself and exercise an aesthetic pleasure will constitute a meaningful assertion of her power. The trouble here is that it’s not just one nail polish advertisement that links meanings of empowerment with a beauty product. The messages in this advert connect to those in other types of media texts (films, tv shows, ads/branding campaigns, celebrity images) as well as to cultural values that equate women’s work on their beauty/bodies with self-improvement. This sort of messaging about “empowerment” reinforces the idea that beauty routines are a necessity for presenting ourselves as socially acceptable and transform the pursuit of beauty into an oppressive journey of conformity.

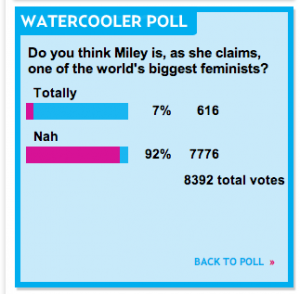

Although feminism and feminist may currently be nebulous terms, there exists nonetheless an understanding among the public about what feminism, in essence, means. A poll conducted on People Magazine‘s website found that 92% of those who responded did not think that “Miley is, as she claims, one of the world’s biggest feminists.”

In early twenty-first century Western culture, it’s not a leap to argue that meanings and practices of feminism have become distorted and distant from their origins or that they have come to be associated with beauty-related goods and issues in consumer culture. Feminism is not a catch all for anything that involves a woman feeling good about herself, nor is it an excuse for a woman’s bad behavior. There is much feminist work to be done (see, for instance, recent studies on gender pay gaps here and here). As a culture and as individuals, we need to start thinking more about what we want feminism to be and do for women and society. Miley’s brand of feminism opened up a conversation. Let’s continue it.