I am working on a dissertation about self-documentation and social media and have decided to take on theorizing the rise of faux-vintage photography (e.g., Hipstamatic, Instagram). From May 10-12, 2011, I posted a three part essay. This post combines all three together.

Part I: Instagram and Hipstamatic

Part II: Grasping for Authenticity

Part III: Nostalgia for the Present

Part I: Instagram and Hipstamatic

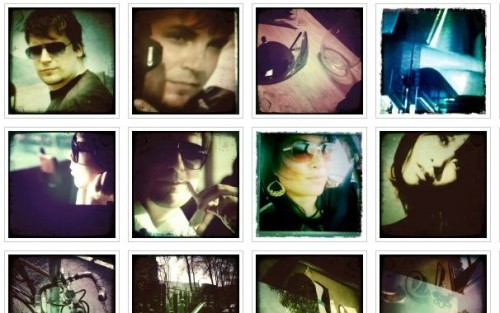

This past winter, during an especially large snowfall, my Facebook and Twitter streams became inundated with grainy photos that shared a similarity beyond depicting massive amounts of snow: many of them appeared to have been taken on cheap Polaroid or perhaps a film cameras 60 years prior. However, the photos were all taken recently using a popular set of new smartphone applications like Hipstamatic or Instagram. The photos (like the one above) immediately caused a feeling of nostalgia and a sense of authenticity that digital photos posted on social media often lack. Indeed, there has been a recent explosion of retro/vintage photos. Those smartphone apps have made it so one no longer needs the ravages of time or to learn Photoshop skills to post a nicely aged photograph.

In this essay, I hope to show how faux-vintage photography, while seemingly banal, helps illustrate larger trends about social media in general. The faux-vintage photo, while getting a lot of attention in this essay, is merely an illustrative example of a larger trend whereby social media increasingly force us to view our present as always a potential documented past. But we have a ways to go before I can elaborate on that point. Some technological background is in order.

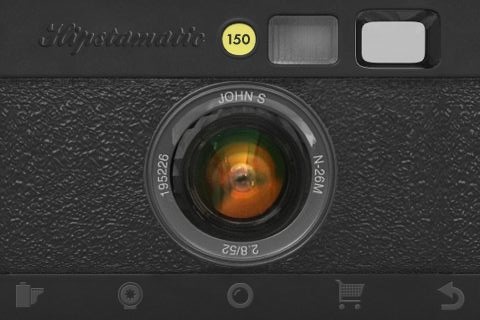

The first very popular app that made your photographs instantly retro was Hipstamatic app. Instagram is even more powerful with its selection of multiple “filters,” that is, different flavors of vintage (a few not-so-vintage filters are available, too). Instagram also features a popular social networking layer that allows users to contribute and view a stream of Instagram photos with “friends.” Other retro photography applications are available as well.

What do these apps do? Among other things, they fade the image (especially at the edges), adjust the contrast and tint, over- or under-saturate the colors, blur areas to exaggerate a very shallow depth of field, add simulated film grain, scratches and other imperfections and so on. And, importantly for the next post, the photos are often made to mimic being printed on real, physical photo paper. And many of our Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter, etc. streams have become the home to one of these vintage-looking photos after another.

Why Faux-Vintage Now?

This trend was made possible due to the rise of smartphones because smartphone photography has at least three important differences from the previous (and increasingly endangered) point-and-shoot digital cameras: (1) your smartphone is more likely to be on you all the time, even while sleeping, than was even the most portable point-and-shoot; (2) the smart phone camera exists as part of a powerful computer-software ecosystem comprised of a series of applications; and (3) the smartphone is typically connected to the Internet in more ways and more often than previous cameras were. Thus, the photos you take are more likely to be social (opposed to for personal consumption only) because the camera is now always with you in social situations, and, most importantly, the device is connected to the web and exists within a series of other apps on your smartphone that are often capable of delivering content to various social media. Beyond being social, the applications make it far easier to apply different filters to photos than did point-and-shoot cameras or using photo editing software on your computer.

But the question I am asking with this essay is not just about the rise of digitally manipulated social photography, but why these digitally manipulated photos showing up in our social media streams are manipulated specifically to look vintage. Why do so many of us prefer to take, share and view these faux-aged photos?

Is Picture-Quality the Reason?

Perhaps, as another blogger noted, it is the low quality of phone cameras that has lead to the rise of faux-vintage. Maybe the current quality of smartphone cameras tends to produce stale photographs which are then made more interesting when given a faux-vintage filter? Photographers have long known that, depending on the situation, a gritty photo can be as good as or better than a technically perfect shot, and now everyone with a smartphone can take an interesting picture with just one additional press of a button. But, this explanation does little to explain why we equate vintage with interesting in the first place. [Also, many current smartphone cameras are of high quality].

Poets and Scribes?

Another reason for the rise of faux-vintage photography might be that these apps allow us to be more creative with our photos. Susan Sontag in the wonderful On Photography discusses how photography is always both the capturing of truth as well as a subjective creation. In this sense, when taking a photograph we are at once both poets and scribes; a point that I have used to describe our self-documentation on social media: we are both telling the truth about our lives as scribes, but always doing so creatively like poets. So, if “photography is not only about remembering, it is [also] about creating,” then the rise of smartphones and photo apps have democratized the tools to create photos that emphasize art, not just truth. But, again, this explanation would only explain why we might want to manipulate photos in the first place. It does not explain why so many of us have so often chosen to manipulate them into looking specifically retro/vintage.

Part II: Grasping for Authenticity

So far I have described what faux-vintage photography is and noted that it is a new trend, comes primarily from smartphones and has proliferated on social media sites like Facebook, Tumblr and others. However, the important question remains: why this massive popularity of faux-vintage photographs?

What I want to argue is that the rise of the faux-vintage photo is an attempt to create a sort of “nostalgia for the present,” an attempt to make our photos seem more important, substantial and real. We want to endow the powerful feelings associated with nostalgia to our lives in the present. And, ultimately, all of this goes well beyond the faux-vintage photo; the momentary popularity of the Hipstamatic-style photo serves to highlight the larger trend of our viewing the present as increasingly a potentially documented past. In fact, the phrase “nostalgia for the present” is borrowed from the great philosopher of postmodernism, Fredric Jameson, who states that “we draw back from our immersion in the here and now […] and grasp it as a kind of thing.”*

The term “nostalgia” was coined more than 300 years ago to describe the medical condition of severe, sometimes lethal, homesickness. By the 19th century the word morphs from a physical to a psychological descriptor, not just about the longing of a place, but also a longing for a time past that, except through reminders, one can never return to. Indeed, this is Marcel Proust’s favorite topic: the ways in which sensory stimuli have great power to invoke overwhelmingly strong feelings and vivid memories of the past; precisely the nostalgic feelings that faux-vintage photos seek to invoke.

Faux-Physicality as Augmented Reality

One important way in which the digital photo does this is by looking like it is not a digital photo at all. For many, and especially those using faux-vintage apps, photography is primarily experienced in the digital form: snapped on a digital camera and stored and shared via digital albums on computers and websites like Facebook. But just as the rise and proliferation of the mp3 is coupled with the resurgence of vinyl, there is a similar reclaiming of the aesthetic of the physical photo. Physicality, with its weight, smell and tactile interaction, grants a significance that bits have not (yet) achieved. The quickest way to invoke nostalgia for a time past with a photograph is to invoke the properties of the physical, which is done by mimicking the ravages of time through fading, simulated film grain and scratches as well as the addition of what appears to be photo-paper or Polaroid borders around the image.

This follows the trend of what I have labeled “augmented reality”: the fact that physical and digital are increasingly imploding into each other. And by making our digital photos appear physical, we are attempting to purchase the cachet and importance that physicality imparts. I’ve noted in the past this trend to endow the physical with a special importance. I commented on the bias to view physical books as more “deep” than digital text. I also critiqued those who label digital activism “slacktivism” and those who view digital communication as inherently shallow. Why would we grant the physical photo special importance?

This follows the trend of what I have labeled “augmented reality”: the fact that physical and digital are increasingly imploding into each other. And by making our digital photos appear physical, we are attempting to purchase the cachet and importance that physicality imparts. I’ve noted in the past this trend to endow the physical with a special importance. I commented on the bias to view physical books as more “deep” than digital text. I also critiqued those who label digital activism “slacktivism” and those who view digital communication as inherently shallow. Why would we grant the physical photo special importance?

Perhaps the answer is because the physical photograph was scarce. Producing a photo took longer and cost more money prior to the advent of digital photography. This is one of the main differences between atoms and bits: the former is scarce and the later is abundant; something I have written about before. That an old photo was taken and has survived grants it an authority that the equivalent digital photo taken today cannot achieve. In any case, that the faux-vintage photograph aspires to physicality is only part of why they have become so massively popular.

Nostalgia and Authenticity

I submit that we have chosen to create and view faux-vintage photos because they seem more authentic and real. One does not need to be consciously aware of this when choosing the filter, hitting the “like” button on Facebook or reblogging on Tumblr. We have associated authenticity with the style of a vintage photo because, previously, vintage photos were actually vintage. They stood the test of time, they described a world past, and, as such, they earned a sense of importance.

People are quite aware of the power of vintage and retro as carriers of authenticity. Sharon Zukin’s book Naked City expertly describes the recent gentrification of inner cities as the quest for authenticity, often in the form of grit and decay. For those born in the plastic, inauthentic world of suburban Disneyfied and McDonaldized America, there has been a cultural obsession with decay (“decay porn”) and a search for authentic reality in our simulated world (as Jean Baudrillard might say).

The faux-vintage photos populating our social media streams share a similar quality with the inner-city Brooklyn neighborhood rich with authentic grit: they conjure authenticity and real-ness in the age of simulation and the vast proliferation of digital images. And, in this way, the Hipstamatic photo places yourself and your present into the context of the past, the authentic, the important and the real.

But, of course, unlike urban grit or the rarity of an expensive antique, the vintage-ness of a Hipstamatic or Instagram photo is simulated (the faux in faux-vintage). We all know quite well that these photos are not really aged with time but instead by an app. These are self-aware simulations (perhaps the self-awareness is the hipster in Hipstamatic). The faux-vintage photo is more similar to a fake 1950’s diner built many decades later. They are Main St. in Disney world or the fake checkered cab in the New York, New York hotel and casino complex in Las Vegas. These are all simulations attempting to make people nostalgic for a time past. Consistent with Baudrillard’s description of simulations, photos in their Hipstamatic form have become more vintage than vintage; they exaggerate the qualities of the idea of what it is to be vintage and are therefore hyper-vintage.

The very thing that a faux-vintage photo provides, authenticity, is thus negated by the fact that it is a simulation. However, this fact does preclude these photos conjuring feelings of nostalgia and authenticity because what is being referenced is not “the vintage” but “the idea of the vintage,” similar to the simulated diner, modern checkered-cab or Disney Main St.; all hyper-real versions of something else and all quite capable of causing and exploiting feelings of nostalgia. Therefore, simply being aware that the authenticity Hipstamatic purchases is simulated does disqualify the faux-vintage photo from entering into the economy of the real and authentic.

Part III: Nostalgia for the Present

The rise of faux-vintage photography demonstrates a point that can be extrapolated to documentation on social media writ large: social media users have become always aware of the present as a potential document to be consumed by others. Facebook fixates the present as always a future past. Be it through status updates on Twitter, geographical check-ins on Foursquare, reviews on Yelp, those Instagram photos or all of the other self-documentation possibilities afforded to us by Facebook, we view our world more than ever before through what I like to call “documentary vision.”

Documentary vision is kind of like the “camera eye” photographers develop when, after taking many photos, they begin to see the world as always a potential photo even when not holding the camera at all. The habit of the photographer involuntarily framing and composing the world has become a metaphor for those trained to document using social media. The explosion of ubiquitous self-documentation possibilities, and the audience for our documents that social media promises, has positioned us to live life in the present with the constant awareness of how it will be perceived as having already happened. We come to see what we do as always a potential document, imploding the present with the past, and ultimately making us nostalgic for the here and now. And there is no better paradigmatic example for this view of the present as always a potential documented past than the faux-vintage photo (why I have chosen this as a topic for essay). The faux-vintage photo asks the viewer to suspend disbelief about the authenticity of the simulated nostalgia and to see the photo–and who and whatever is in it–as being authentic and important by referencing at least the idea of the past. While, technically, all photographs, indeed all documentation, conjure the past, the faux-vintage photograph serves to vividly underscore and make even more clear our efforts to display our lives in the present as already a past to feel nostalgic for.

And there is no better paradigmatic example for this view of the present as always a potential documented past than the faux-vintage photo (why I have chosen this as a topic for essay). The faux-vintage photo asks the viewer to suspend disbelief about the authenticity of the simulated nostalgia and to see the photo–and who and whatever is in it–as being authentic and important by referencing at least the idea of the past. While, technically, all photographs, indeed all documentation, conjure the past, the faux-vintage photograph serves to vividly underscore and make even more clear our efforts to display our lives in the present as already a past to feel nostalgic for.

The faux-vintage photograph is self-aware of itself as document. If regular photos placed on Facebook walls document that we exist, the faux-vintage photo is this but also more than this: it is also a reference to documentation itself. This double document–a document of documentation–becomes further proof that we are here and we exist. The rise of faux-vintage photographs, snapped on smartphones and shared via social media, is centrally an existential move that is deployed because conjuring the past creates a sense of nostalgia and authenticity.

But the ultimate irony is that while these tools, just like all of social media, help us reinforce to ourselves and others that we are real and authentic, but they do this by simultaneously divorcing us to some degree from experiencing our present in the here and now. Think of a time when you took a trip holding a camera and then think of when you did the same without the camera; most of us have probably traveled both with and without a camera in our hands and we know the experience is at least slightly different; some might claim radically different. With so many documentation possibilities (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Yelp, Foursquare and so on), we are always, both literally and metaphorically, living with the camera in our hands. When discovering a new bar or a great slice of pizza we might think of posting a review on Yelp; when overhearing a funny conversation we might think to tweet it; when hanging out with friends we might create a status update for Facebook; and when at a concert we might find ourselves distracted by needing to take and post a photo of the event as it happens. When the breakfast I made the other week looked especially delicious, I posted a photo of it before even taking a bite.

My larger dissertation project will be to explore these points and demonstrate specifically how this newly expanded documentary vision potentially changes what we do. Does knowing that you will check in on Foursquare at least slightly influence what restaurant you’ll choose to eat at? In what other ways is our online documentation not just a reflection of what we do but also sometimes (or always?) a cause? To go straight to the extreme case, I once overheard a young inebriated woman on the subway around 2am state that “the real world is where you take pictures for Facebook.” She was, I thought, the smartest person on that train.

What Will Become of the Faux-Vintage Photo?

Let me conclude this all by coming back to faux-vintage photos specifically. I think they might be a passing fad.

Let me conclude this all by coming back to faux-vintage photos specifically. I think they might be a passing fad.

Faux-vintage photos devalue and exhaust their own sense of authenticity, which portends their disappearance because, as I described in part II, authenticity is the very currency by which they have become popular; there is an inflation as a result of printing too much currency of the real. For instance, the faux-vintage photo will no longer be able to conjure the importance associated with physicality (another point made in part II) if the vintage look begins to be more closely associated with smartphones than old photos. The novelty begins to wear off and the nostalgia fades away.

Most damning for Hipstamatic and Instagram is that these apps tend to make everyone’s photos look similar. In an attempt to make oneself look distinct and special through the application of vintage-producing filters, we are trending towards photos that look the same. The Hipstamatic photo was new and interesting, is currently a fad, and it will come to (or, already has?) look too posed, too obvious, and trying too hard (especially if the parents of the current users start to post faux-vintage photos themselves).

To be clear, photographic techniques like saturation, fading, vignetting and others are not essentially good or bad (for instance, I love these faux-vintage shots). But when so widely used they seem less like an artistic choice and more as if they are merely following a trend (what Baudrillard called the “logic of fashion”). The ironic fate that extinguishes so many trends built on suggesting and exploiting authenticity is that their very popularity extinguishes that which made them popular.

The inevitable decline (but not full disappearance) of the faux-vintage photo will be our collective decision that the style is beginning to appear increasingly posed, contrived and passé, and thus negating the feelings of authenticity that were the very reason we liked them in the first place. Another retro-looking photo of a sunny country road, a dandelion, or your feet?

*quote is from page 284 of Jameson’s Postmodernism: Or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke University Press, 1991.

Follow Nathan on Twitter: @nathanjurgenson

This essay has been translated into French here.

Also: Faux-Vintage Afghanistan and the Nostalgia for War.

Credit for the snowstorm image: http://tballardbrown.tumblr.com/

Credit for the Disney castle image: http://www.flickr.com/photos/chel1974/4578467229/in/photostream/

Credit for the Hipstamatic photogrid: http://www.myglasseye.net/

Credit for the final image, from: http://www.etsy.com/listing/61906957/photographic-memory-print?ref=pr_shop

Comments 201

Elliott Payne — May 14, 2011

Or, maybe, just maybe, the quality of smartphone cameras are still of low enough quality that the inherent noise of using such a small sensor makes masking that poor quality photo with a faux-vintage filter ( where "real" vintage = noise & grainy) helps to pass off an otherwise crappy photo as something more interesting.

You make some interesting points about social interaction in general, but I think you're streching your thesis a bit much by making your point using photo filters as the example. If anything, this fad will pass when smartphone have more capable lowlight performance.

nathanjurgenson — May 15, 2011

i do take on this issue early in the essay, and what i would want to ask is why, with all the edits possible, it is vintage that passes as "interesting"? why the explosion of that? also, many smartphone cameras are indeed of high quality, and the faux-vintage trend proliferates on those, too.

but, i do agree that faux-vintage filters alone are too flimsy an example to hold the argument. i argue above that they are just one (passing) example of something larger about ALL self-documentation on social media.

James Rhem — May 15, 2011

The larger question as I see it is whether or not the longing for the past, which is often seen as a better time, is a healthy, helpful social habit, one that helps us rebalance the present by remembering and taking pleasure in aspects of the past or whether nostalgia and fashion are somehow the same thing and of similar importance.

teddave — May 15, 2011

interesting essay though i agree with the comment above: fone pics only work as filtered images; unfiltered pics dont cut it (yet). however you might want to consider further theorising the original polaroid and its role as artefact.

Atemporality, the iPhone Camera, and the Hipster | varnelis.net — May 15, 2011

[...] at Cyborgology, Nathan Johansen dissects the "Faux-Vintage Photo" to uncover how individuals today seek to occupy the near [...]

Elliott Payne — May 16, 2011

Yup, I skimmed the article & missed your point about picture quality.

Under optimal lighting conditions, the iPhone 4 has excellent photo quality. But often times, the moments you want to share don't provide good light (late night dinners, parties, etc.). So I think we both agree that post processing is a completely appropriate facet of sharing. So then the question boils down to why the vintage look is more "interesting" than any other post processing methods.

It comes down to 2 things in my opinion:

1) the assumption is that the starting point is a low quality (noisy, grainy) photo.

2) what is the "modern" processing technique that would contrast a vintage approach?

The answer here is that there isn't any modern processing technique (such as HDR) that can mask a poor quality photo. So rather than fight the tide, using a vintage filter embraces the quirkiness of the smartphones' weaknesses rather than try to enhance.

POSZU - — May 16, 2011

[...] A long article has been making the rounds, which at first catches the eye because of the copious (if mis-directed) use of a great many technospheric buzz words, popular smart phone app titles, and a splattering of post-modern philosophy, but then when unpacked devolves into all-too-typical post-Baudrillard simulacrap. BUT, just because it is misdirected, doesn’t mean that we can’t learn something from it, and take this opportunity to redirect. [...]

André — May 16, 2011

awesome essay. lots to say in response. I collected my thoughts here: http://learnoutlive.com/how-social-media-killed-the-moment/ - in any case - keep up the great work!

hapa — May 16, 2011

dunno. thought maybe people got sick of making wacky faces and delegated that job to the scenery.

Real world – Rameez Nooruddin — May 16, 2011

[...] Nathan Jurgenson in The Faux-Vintage Photo Related posts:A folder containing every movie in the [...]

nick — May 16, 2011

very interesting post. when reading it i jotted a note saying "how does the simulation negate 'authenticity'? what if 'authenticity' is merely an culturally dynamic aesthetic, and not some essential quality?". i'm very interested in the assumption that you appear to make that 'authenticity' is 'authentic', basically, the idea of authenticity itself. what existential function demands it? i can only hope to discover more of your writings & bibliographies!

Darren — May 16, 2011

How about the rise in popularity of Lomography, shooting with the many "Toy", film cameras that are becoming more and more popular. These cameras are authentically producing the "look" Instagram and Hipstamatic are imitating, yet are not mentioned at all in the article.

I would wager that the market segment populated by Holga and Lomo derivatives is the only segment of analog photography that has shown any growth at all in the past few years. Considering their relatively parallel upwards trends, I think you have missed some important information.

Niels — May 16, 2011

Absolutely brilliant. Thank you for the nice read.

Mike — May 16, 2011

Excellent piece. "Documentary vision" nicely names the phenomenon; I'd written about it without the benefit of such an apt phrase. I'm working on similar issues from the perspective of the history of memory practices. Tend to think the visual nature of social media remembering/documenting accents the presence of the absent thing rather than its "past-ness." I'm going off of Ricoeur's distinction between the Platonic and Aristotelian views of memory; the presence of the absent thing vs. the remembrance of a past in time. Perhaps the faux-vinatage look is a gesture toward the acknowledging the pastness of the present absence.

Michael D Dwyer — May 16, 2011

Lots to think about here, as I've been doing research on nostalgia culture for the last few years, but two things jump immediately two mind:

1) I'm not so sure that social media services as they exist now are really invested in in treating the present as a potentially documented past--it is nearly impossible to access old statuses, updates, notes and comments on the social media platforms that are dominant today, which is one way that social media in 2011 is considerably different from, say, LiveJournal in 2002. In fact, I think one of the ways these services encourage constant user updates is to de-emphasize the potential of your posts to last, and to continuously demand new content to keep you from slipping into the past.

2) Jameson's argument about nostalgia in Postmodernism regards the inability of postmodernist culture to represent its immediate material conditions. But as this essay itself shows, the movement towards nostalgia in contemporary culture, and its affective power, are *deeply historical*. In other words, I'm not so sure that nostalgia necessarily = the simulacrum, and lots of the best writing on nostalgia has worked to go beyond Jameson's characterization of it in 1983 (Richard Dyer's _Pastiche_, for example).

Michael D Dwyer — May 16, 2011

PS - I wish I could edit that comment to make it sound less snooty (that first paragraph...who says that?). M'bad. I think it's a really interesting essay that could productively go in a lot of important directions.

ANoobis.EIdo — May 17, 2011

oh this sounds like haven I is so intrigued with this load of infinitely cyclical regress

Faux vintage photography | SRPS Blog — May 17, 2011

[...] vintage photography Posted on May 17, 2011 by scott Tweet Here’s a thoughtful piece on faux vintage photography by Simon Sellars. I’ve been experimenting recently with a few of [...]

Corey — May 17, 2011

I think Hipstamatic speaks more to the polaroid experience. We all know that polaroids didn't have great quality, but they did offer the ability to capture a moment. Taking a picture with a polaroid camera was part of the experience. It required patience, it was exciting to watch it develop.

Instagram allows the user to add several different filters to the image after the fact. While Hipstamatic requires you to choose your lens, film, and flash BEFORE you shoot, and then requires that you wait for it to "develop".

I think that Instagram and Hipstamatic both produce a similar look, but I think that the experience is much different. For me, Hipstamatic brings back the nostalgic feeling of an old film camera and a darkroom.

Too many aspects of the "feel" and experience of these apps are being glossed over.

Alex — May 17, 2011

Too bad that often we can't see that whatever quality the 'unadulterated' versions of these images really WILL form the patina of the future. How is it that we view the present as so pristine?

The Faux-Vintage Photo | brundlefly — May 17, 2011

[...] Cyborgology: This past winter, during an especially large snowfall, my Facebook and Twitter streams became inundated with grainy photos that shared a similarity beyond depicting massive amounts of snow: many of them appeared to have been taken on cheap Polaroid or perhaps a film cameras 60 years prior. However, the photos were all taken recently using a popular set of new smartphone applications like Hipstamatic or Instagram. The photos (like the one above) immediately caused a feeling of nostalgia and a sense of authenticity that digital photos posted on social media often lack. Indeed, there has been a recent explosion of retro/vintage photos. Those smartphone apps have made it so one no longer needs the ravages of time or to learn Photoshop skills to post a nicely aged photograph. [...]

James Campbell — May 17, 2011

Seriously both apps over filter the hell out of photos. I want to see your photographic vision, not hipstamatic. That being said, there are always exception and composition remains king. What I notice is with the bar lowered for entry, the ubiquitous posting and sharing to Flickr, etc, what the curator is left with is just more rubbish to sift through. Good photos still rise to the top. Even among millions of pictures of over processed shoes, feet, people walking, coffee cups, cats, and other cliches.

I think you missed the true heart of the matter with this social age. It feels really good to get near instant feedback and praise from your peers when you take and post a photo. That is what is driving this new creative market, people's feeling of accomplishment and worthiness based on peer and complete stranger feedback.

I feel like instagram is more a sharing platform and less a photo app, and hipstamatic is an app up you buy when you first get an iPhone and you quickly move on to better photo apps one you realize you photos all look hipstamatic and not your own style. For pro level alternatives, I suggest filterstorm and iris photo studio as well as photogene.

I am heading to NYC to moderate an apple talk on portraits with an iPhone this Thursday at the upper west side apple store and I will be discussing many of these points with the interviewee Jim Darling.

James Campbell — May 17, 2011

Haha, please excuse the typos / weird grammar. My iPad keyboard really hates me tonight, or I should just type slower and check what I am writing.

gaby — May 17, 2011

Nathan, I wonder about the extent to which you find 'nostalgia for the present' in social media to be (at least phenomenologically) different from the type experienced by and inherent to pack-rats, obsessive diarists and others I might call 'self-curators.' In other words, the type of 'documentary vision' you describe is not only cultivated by people who see the world as a potential past to be consumed by others, but is also cultivated by people who see the world as a potential past to be revisited for themselves later. What is the difference or significance of any difference between using that filter with the expectation of consumption by OTHERS (implicit in social media engagement), and simply the use of that filter for oneself?

Social Media and the Arts of Memory « The Frailest Thing — May 19, 2011

[...] of this point anchored on an analysis of faux-vintage photography see Nathan Jurgenson’s, “The Faux-Vintage Photo.”) Drawing in Manovich’s database/narrative opposition, suggests that the visual/spatial mode [...]

chris — May 22, 2011

I worked at an Amusement Park during college as many people in my family have. For a few years now I've been working on making a movie about the place and my experience/feelings about it. When I started the piece I picked up a copy of Simulation and Simulacra but wasn't able to really comprehend its significance with what I was doing. About 3 years have passed and I've really gotten nowhere on the project. At the present I have been using my Holga and Super 8mm for various projects. I have to be honest and say that in reading this post, things just sort of clicked for me and I think I've found a new direction for this project. Thank you!

Tanya Ballard Brown — May 23, 2011

Hey! I took that NPR pic at the top. How cool to see it being used in this way.

Michael Max — May 23, 2011

I don't know about nostalgia. But, I do know that with "regular" digital photography these days there are endless modifications you can make photo editing software. For me, the beauty of Hipstamatic is that it freezes a moment in time that DOES NOT lend itself to endless editing and adjustment.

In this age of easy to reproduce and easy to edit, there is something comforting about a moment frozen in time.

New Technology & Old World Style — May 23, 2011

[...] other smartphone) apps [Nathan Jurgenson offers an interesting, if long, analysis of the phenomenon here.] We just like old-looking things with modern convenience. No related posts found. [...]

Brandon — May 24, 2011

Great essay and nice writing. You've done an interesting job of articulating on a very intangible concept. It would be nice to see a bit more citation and research to balance out some of the longly worded ideas you've presented. However, I know this isn't your finished dissertation, so no big deal. Another small suggestion would be to replace cache with cachet. I think that was the word you intended to use, otherwise the use of cache in that sentence didn't seem quite apposite.

It feels like the use of these apps doesn't actually allow the user to be more creative, but actually promotes some lethargy towards actually making a well composed, exposed, and timed photograph. The apps actually seems to counterbalance/cover-up the user's inexperience and laziness with a catchy mask that allows him or her to say, "Look, I'm an artist too."

owen-b — May 27, 2011

Nice to see my grid of Hipstamatic film and lens combinations being used in a thoughtful essay, as opposed to one which just outright slams users of these apps as not being 'proper photographers' - a good balanced debate here!

But, I'd appreciate a link to my website in the article footer too, thanks :)

(www.myglasseye.net)

The Faux-Vintage Photo » OWNI.eu, News, Augmented — June 2, 2011

[...] about self-documentation and social media and wrote this essay for his Cyborgology blog.Find the original post here. It is replicated on OWNI with the author’s [...]

The SIP » The Faux-Vintage Photo Part 1: Hipstamatic and Instagram — June 3, 2011

[...] about self-documentation and social media and wrote this essay for his Cyborgology blog.Find the original post here. It is replicated on The SIP with the author’s [...]

Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité ou La Mort — June 3, 2011

[...] me va a dar algo, grave. Así que mejor que vaya pensando qué va a hacer al respecto. Lo mismo que tanto aparatito tecnológico que se está comprando, no solo que me está matando a mí, sino que también a todo un planeta, a [...]

Plain talking. Do you think they’d have me? | Sophie Barr's Blog — June 9, 2011

[...] taken on your mobile and circulated on Facebook. Check out this essay by Nathan Jurgenson about the Hipstamatic image where I nicked this idea from. It’s a bit like what I do in my work. It’s all a bit faux, [...]

Andrea McLaughlin — June 13, 2011

Your view of social media trends through a popular photography filter is fascinating to me, as a photographer. A good example of social media as self-documentation can be found on Instagram, usually thought of as an app for photographers, about photography, where there are a number of young women whose posts are all photos OF themselves, and about themselves (a la Facebook)- having nothing to do with the practice of photography. However there is a good deal more going on with social media photography than a nostalgic faux-vintage fad. Look more deeply at the rising popularity of both Lomography and iPhoneography (with filters). Ask more photographers (people whose primary means of expression or source of income is photography) what they think too.

Sam Krisch — June 14, 2011

I am a photographer who prints my Hipstamatic pictures and shows them in galleries. How does the thesis hold up when these images populate the physical world?

I find that when I use my full frame pro DSLR I often age my photography using Photoshop. I exhibit these photographs in physical prints as well.

Should I stop using those tools because somehow others use them to produce bad images?

In my case, I am attempting to reference to an older look that inspires and communicates mood and atmosphere. I have captured images using both iPhone and DSLR at the same event and often like the iPhone images better. The phone allows me to gain a sense of play and spontaneity that helps produce interesting results.

Artists and writers in every medium are influenced by and reference older art. As T.S. Eliot wrote: "Immature artists borrow, mature artists steal."

I think it depends on the artist's imagination, intention and practiced eye, not so much on what

equipment or post-process the photographer uses.

In the end, any tool can produce either gold or lead. We all know that technique alone is not enough. Why not use tools that are available, even (especially) if others cannot produce anything worth seeing?

Phoebe — June 14, 2011

Cheers for sharing your insight with us on the post-nostalgic culture! I'm currently working on my thesis on steampunk fiction so it's interesting to see how another medium interprets and represents this trend of playing, or rather, commodifying, nostalgia.

Sam Krisch — June 15, 2011

My website is www.samkrisch.com

Also, check out my post on this subject. http://samkrisch.wordpress.com/2010/07/19/hipsta-is-as-hipsta-does-adventures-in-iphone-art-photography/

AND my book which is called, ironically enough REMEMBERING THE PRESENT:Portraits of Burma.

Thanks Nathan and Andrea!

Sam Krisch — June 15, 2011

Book link: http://www.blurb.com/bookstore/detail/2187169

Phoebe — June 16, 2011

Have you read Elizabeth Outka's 'Consuming Traditions, Modernity, Modernism and the Commodified Authentic'? It touches on a lot of points that you make in your essay, such as the search for the commodified authentic in places dominated by hegemonic designs and aesthetics, the the friction between the elitist desire to escape the marketplace and the gravitational force it holds with its alluring advertisements...etc. But one thing that she mentions which I found particularly interesting is the idea of the commodified authentic as a performance, transgressive because it delivers what used to be exclusive to the mass, and normative because it establishes normative expressions of authenticity and permanence.

how soon is now that’s what i call music – lexrob.com — June 20, 2011

[...] and has become a societal disposition. Nathan Jurgenson, in an excellent essay, “The Faux-Vintage Photo”, observes a “trend of our viewing the present as increasingly a potentially documented [...]

Rafael — June 29, 2011

Good article. But couldn't it be just that people want to manipulate and enhance their images in creative ways that up until then were only available to professional photographers. In this sense, the faux-vintage is only a large repertoire of styles and ways in which images can be manipulated, not necessarily with any reference to the past. Let's not forget that effects such as tilt-shift, HDR, panoramics and even kyte aerial are also booming, some of them even included in mobile apps. I suspect most of users of Instagram and Hipstamatic are not thinking about the past or about the history of photography when they use the effects. Probably a good number of them don't even know there are old film cameras able to achieve this effects. They just think it looks cool, and would use futuristic effects if they looked as good. They are postmodern bricoleurs using anything available to express themselves, no matter the meanings or references.

The Faux-Vintage Photo Part 1: Hipstamatic and Instagram | SIP — July 2, 2011

[...] about self-documentation and social media and wrote this essay for his Cyborgology blog.Find the original post here. It is replicated on The SIP with the author’s [...]

Jaime — July 3, 2011

So how would this fit into the discussion: 102 year old lens on a 5DmkII

http://www.cinema5d.com/viewtopic.php?p=133996#p133942

Whenever I think of the past (1900s) I think in terms of black and white and silver gelatin looking prints. If I think of my great grandfather and his travels around the world I see them in terms of black and white because that is how I've "seen" it. Movies do it. The prints from that era show it.

And now when I look at the pictures from a hundred-year-old lens on this new camera -- my perceptions of what the past "is" has been skewed.

Marcus — July 3, 2011

Very interesting post.

Have you read Flusser’s Towards a Philosophy of Photography?

I think you’d appreciate his argument, that the camera encodes the photographer much more than the photographer.

Other Ten Percent » Other Ten Percent 7/4/11 — July 4, 2011

[...] The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II and III) Here is a an essay Bruce Sterling linked about why you’re terrible because of Hipstamatic. WARNING: It is a holiday so there will be no more warnings. It’s going to be a quick one. Sorry. [...]

Bill Latocki — July 4, 2011

Don't look back, I say. And I quote Kim Clement: "We are somewhere in the future and we look much better than we look right now."

pinboard July 5, 2011 — arghh.net — July 5, 2011

[...] The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II and III) » Cyborgology RT @bruces: #Atemporality [...]

The Faux-Vintage Photo: Cyborgology « CSU Photo — July 8, 2011

[...] Read the post here: The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II and III) » Cyborgology. [...]

Faux-Vintage Photography - Beer & Coffee - Curated by David Hilgier — July 13, 2011

[...] morning’s “while drinking my coffee” reading material was Nathan Jurgenson’s post The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II, and III), forwarded along to me by Genghis Kern. I found the author’s points about social interaction [...]

The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II and III) » Cyborgology « Becky's Blog — July 16, 2011

[...] The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II and III) » Cyborgology [...]

Rethinking Privacy and Publicity on Social Media: Part I « n a t h a n j u r g e n s o n — July 17, 2011

[...] essay, like the one I posted last month on faux-vintage photography, is me hashing out ideas as part of my larger dissertation project on self-documentation and social [...]

Life Becomes Picturesque: Facebook and the Claude Glass » Cyborgology — July 25, 2011

[...] on social media. I recently posted some thoughts on rethinking privacy and publicity and I posted an earlier long essay on the rise of faux-vintage Hipstamatic and Instagram photos. There, I discussed the “camera eye” as a metaphor for how we are being trained to view our [...]

Fausses photos vintages » OWNI, News, Augmented — July 30, 2011

[...] initialement publié sur CyborgOlogy et repéré par Owni.eu Nathan Jurgenson, l’auteur de cet article, travaille sur une thèse [...]

JC Polgár — August 3, 2011

This is a very interesting article. I think Instagram is as well a gold mine for many social interests.

But about the vintage effect success, I like very much the beginning of your part II. That is, fake vintage is a mean to relocate our boring images of boring places (not pejoratively speaking) into what seemed to be the fantastic times of 70's, 30's, etc, when people seemed to be free, living in excitement and revolution… In that way, as you say it, we're documenting ourselves our present, to make it more real, but most of all, more important, as facts. That is especially the vintage effect, referring to an image of inaccessible golden age for my generation, that makes possible its symbolic raising.

In a way, 'vintage' is a 'cliché' in a more general doxa, today. Barthes would say, this 'cliché' transforms our history and culture into essence and nature, to create a mythical image. I'm badly referring to wikipedia for quoting him, but I can see this 'cliché' - which is by nature, artificial - is masking the conventionality of our images, precisely claiming it's 'natural'.

This would be, kind of aesthetic 'bourgeoisie' of today, as bourgeoisie always looks for remaining the codes of the past. It's locking us in this golden age, preventing us to be in the move, and putting our minds at rest, because we probably don't manage to move forward and create our codes by ourselves. And this doxa is probably more and more cultivated through medias and the universal huge diffusion of images in advertisement, fashion, tv, etc.

Please excuse my english - we, in france, have really language issues… - and congrats for your writing, this subject is really interesting me as well, more from the photographic side (I think we don't totally digest and assume the fast development of digital photography, and don't manage to move forward creatively with it from now. You're probably right saying the vintage won't last, until we make moves in digital creation)

Best wishes

Snail Mail my Email: Complicating the Mediation Process » Cyborgology — August 8, 2011

[...] communication (such as that seen in the “Snail Mail my Email” campaign) as a form of romanticized nostalgia for a more “authentic” past, facilitated (ironically) through contemporary technologies. It is hyperreal, as the romance and [...]

David Zweig — August 8, 2011

Nathan,

This is an important essay you've written here. There may be other pieces that cover similar territory but I haven't seen them. Comprehensive, compelling, timely. Great stuff.

It also has a lot of nice overlaps with my own research on Fiction Depersonalization Syndrome, and personal experience. To that end I've written a lengthy post on my blog http://memyselfandhim.com/post/8653717259/nostalgia-for-the-present as part response and part new direction.

Autodérision & Mise en abyme : poncifs — August 15, 2011

[...] sociales sous-jacentes qui poussent la jeune génération à l’utiliser à tout va. Mais l’excellent article de Nathan Jurgenson, traduit par Owni, permet d’approfondir le [...]

Doug — August 15, 2011

Great article!

I don't know if 'nostalgia' is really the proper word. Maybe my internal definition of the word is incorrect, but I feel like nostalgia is associated with personal memories. A longing to return to a time you once experienced before. But a large portion of the people using faux-vintage photo software are too young to have ever produced the real versions of what faux-vintage simulates. It's not a "remember-the-good-old-days" type of phenomenon. In fact, I suspect the faux-vintage look is not nearly as popular with people who actually remember the old days. If you ask me it's about escaping our current boring situation.

Old photos are cool just because they're old. There's an other-worldliness to relics of past eras. It's exotic. It's like how a foreign accent makes someone more interesting and attractive. Or that mystical feeling you get looking at an old castle. It's not a part of your general experience and therefore it's interesting. There's this feeling of another culture or system outside your own.

I feel like you're on to something with the idea that authenticity plays a role in the appeal of faux-vintage. However, I don't think the vintage look is appealing because it seems more authentic than an unaltered cameraphone image. Rather, I think the key factor is that the faux-vintage filters offer a way to achieve that other-worldly exotic feeling that is more authentic *than other alterations*. People want to alter their images so that they appear apart from common experience, but without "showing their brush-strokes" as it were. A completely invented filter that doesn't mimic anything would be too artificial, too far removed from common experience. The viewer would be too aware of the photographers effort. The faux-vintage apps hit the sweet spot by mimicking real effects that actually existed and were originally produced un-intentionally. And they mimic them well enough that we're willing to accept them.

Hipstamatic War | haikuforphotography — August 16, 2011

[...] with the Hipstamatic app on an iPhone, I thought of Nathan Jurgensen’s thoughtful take on how faux-vintage photographs are made to create a nostalgia for the present. Sure enough, when I went back to look at his first essay on the issue (which treats this [...]

everydayUX morsels for July 4th – July 23rd — everydayUX Morsels — August 16, 2011

[...] The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II and III) » CyborgologyFantastic post on the rise of the faux vintage photo and the nostalgia for the present. [...]

Rethinking Privacy and Publicity in Social Media | SIP — August 17, 2011

[...] As I’ve argued elsewhere, social media documentation follows the same logic. When we (or someone else) create documents on social media -be they status updates, comments, photos, etc- we do so as both poet and scribe. We are creative in our self-documentation, even when we try to pass that creativity as pure fact (indeed, I think one of the troubles of social media is the same trouble of all self-presentation: we constantly need to pass our fictive and performative selves off as authentic fact). [...]

Life Becomes Picturesque: Facebook and the Claude Glass « n a t h a n j u r g e n s o n — August 29, 2011

[...] on social media. I recently posted some thoughts on rethinking privacy and publicity and I posted an earlier long essay on the rise of faux-vintage Hipstamatic and Instagram photos. There, I discussed the “camera eye” as a metaphor for how we are being trained to view our [...]

Whither the Future? « The Frailest Thing — October 11, 2011

[...] before. The nostalgic turn, however, did not just emerge with Mad Men (and now its imitations) and Instagram’s faux-vintage photo apps. It was noted by scholars in the 1990′s and is complicit with the postmodern repurposing [...]

“Petty” » Self-documentation and Nostalgia for the Present — October 11, 2011

[...] The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay Parts I, II and III » Cyborgology. [...]

Who needs Instagram? (I might) | Skinny laMinx — October 17, 2011

[...] Thanks to reader, Mi Ya, I found this essay on the Instagram phenomenon, which makes a pretty interesting read. This entry was posted in enthusiasm, myself and [...]

Cyborgology One Year Anniversary » Cyborgology — October 26, 2011

[...] in page views, high quality comments, and discussions on sites like Twitter and Facebook. The Faux-Vintage photo essay took on a life of its own and a recent post on Chomsky was rewritten for Salon.com (here). The blog [...]

Experiencing Life Through the Logic of Facebook » Cyborgology — October 27, 2011

[...] discuss in my Faux-Vintage photo essay how social media gives us “the camera eye”, forcing us to view our present as always a [...]

andee — October 27, 2011

Hi, Nathan,

Really interesting ideas you have here. I wondered too if maybe in looking at the historical part of all of this, you may want to go back to the point in earlier cell phone/iPhone use when people first started showing their snapshots they had transferred to their phones. They were so excited to show people a bunch of almost random shots of their families and friends and places they had gone.

Also, do you have any ideas about what may come after the faux-vintage trend? Does this technique make my "real" vintage photos more or less coveted or valuable, do you think?

Retro-Tech: #OWS’ Complicated Relationship with Technology » Cyborgology — November 2, 2011

[...] Surprising to some might be all of the vintage cameras. Be they early-model Polaroid’s or old Kodak brownies, ancient cameras are popular at Occupy Wall Street. A statement that alone justifies this further analysis. Perhaps this trend is the analogue version of the popular faux-vintage smartphone photo apps like Instagram and Hipstamatic that I have written about before. [...]

meng weng wong — November 5, 2011

Thanks for the essay! It reminded me of http://forgetomori.com/2010/fortean/time-traveler-caught-in-museum-photo/

Hipster Rivivalism: Authentic Technologies of Days Gone Past » Cyborgology — November 25, 2011

[...] discussion, you need to know about how hipsters look to the past as a source of authenticity. As Nathan Jurgenson has written about in his work on faux-vintage photography, the obsession with antiquated technologies can best be described as “grasping for [...]

Living Pictures? Lytro’s Photos Are Barely Alive » Cyborgology — November 28, 2011

[...] I have written about Susan Sontag’s description of photographers being always at once poets and scribes when taking photos to describe how we create our social media profiles in a similar way. I have used the concept of the “camera eye” photographers develop to discuss how social media has imbued us with a similar “documentary vision.” I also described how the explosion of faux-vintage photos taken with Hipstamatic and Instagram serve as a powerful example of how social media has trained us to be nostalgic for the present in a grasp at authenticity. [...]

Wat ik zoal zie, lees en deel — December 6, 2011

[...] The Faux Vintage Photo Essay – Een fraai dissertatie over de opkomst en populariteit van Instagram-achtige apps en de zelf-documentatie door social media [...]

2011 in review | À l'allure garçonnière — December 31, 2011

[...] The Faux Vintage Photograph by Nathan Jungerson at The Society Pages (May 11th, 2011) *** this may be my favourite piece of non-fiction writing of the year**** [...]

Michael Chrisman’s Long Now » Cyborgology — January 4, 2012

[...] of the most heavily trafficked posts on this blog in 2011 was Nathan Jurgenson’s excellent essay on “faux-vintage” photography and the construction of meaning in documentation; given [...]

The Real World is Where You Take Pictures for Facebook. « With Care. — January 9, 2012

[...] just finished reading this article about faux-vintage photos (the kind associated with Instagram or Hipstamatic applications) and [...]

The Atemporality of “Ruin Porn” – Part I: The Carcass » Cyborgology — January 12, 2012

[...] Atlantic Cities’ feature on the psychology of “ruin porn” is worth a look–in part because it’s interesting in itself, in part because it features some wonderful images, and in part because it has a great deal to do with both a piece I posted last week on Michael Chrisman’s photograph of a year and with the essay that piece referenced, Nathan Jurgenson’s take on the phenomenon of faux-vintage photography. [...]

It’s Gone, All Gone – Part 1: Instagram and the Faux-Vintage Photograph « New Americana — January 16, 2012

[...] Jurgenson (who provides what might be the most thorough theoretical investigation of Instagram, Hipstamatic, and the faux-vintage photograph) writes that using filters to alter an iPhone photograph is “an attempt to make our photos [...]

The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay Parts I, II and III » Cyborgology « Computational Photography at Georgia Tech — January 18, 2012

[...] The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay Parts I, II and III » Cyborgology. Advertisement GA_googleAddAttr("AdOpt", "1"); GA_googleAddAttr("Origin", "other"); [...]

Victoria in the Snow: An Instragram Gallery - The West of West Review — January 23, 2012

[...] Ah, the instagram photo. What an odd phenomenon. Instagram, the popular iPhone app, has become incredibly popular for its seamless social media capabilities and yet it has languished far from acceptance as an artistic medium. Film devotees, in particular those devoted to lo-fi photography, often disparage the app as a poseur, a phony, digital attempting to invade or appropriate one of the few remaining realms of analogue photography. Artistic digital photographers often malign the low quality of smart phone cameras (though with new phones moving into 8 mp or higher this is set to change). Certainly it is a novel movement. A large group of people socially linked by a state of the art app on a state of the art device that celebrates the long past state of a rather different art. For a fascinating exploration of this development, I recommend Nathan Jurgenson’s essay “The Faux-Vintage Photo” available by clicking on the lin.... [...]

The Data Self (A Dialectic) » Cyborgology — January 30, 2012

[...] differently when we know we can post a photo of an especially delicious-looking meal to Facebook. As I’ve posed before: think of traveling with and without a camera in your hand. The experience is different. Today, we [...]

back to the future | thestate — March 19, 2012

[...] POOF! special effects—these photos display a certain studied nostalgia. Nathan Jurgenson has brilliantly theorised these kinds of «faux vintage photos»—the hipstamaticised, the instagrammed, the lomographied, [...]

The Crisis of Authenticity: Symbolic Violence, Memes, Identity » Cyborgology — March 23, 2012

[...] We are currently facing a cultural crisis of authenticity. Since the early 2000s, we have seen the concept “authenticity” slowly move from margins to mainstream (Reynolds, 2011), encapsulated by feverish celebrity gossip surrounding breakout stars like Lana Del Rey, personified through the rise of the urban hipster as folk devil (those self-professed taste arbiters of cool who ride “fixies” through the urban landscape, collect obscure records, and wear vintage clothes), and exemplified in Web 2.0 and the rise of social media (especially curatorial media like LastFM and more recently, Pintrest), where we are all now encouraged to share, like, and make public pronouncements of our personal tastes. In the contemporary zeitgeist, it seems that we are all “grasping for authenticity” in an attempt to make our lives seem more important, substantial, and relevant (Jurgenson, 2011). [...]

Instant Classic: The Rise of Nostalgia Branding | Sparksheet — April 3, 2012

[...] “The ironic fate that extinguishes so many trends built on suggesting and exploiting authenticity is that their very popularity extinguishes that which made them popular,” argues Nathan Jurgenson in the online sociology journal The Society Pages. [...]

#TtW12 Panel Spotlight: Self Documentation » Cyborgology — April 6, 2012

[...] media increasingly force us to view our present as always a potential documented past” (Jurgenson, 2011). In this vein, Sam Ladner addresses the proliferation of digital calendaring (MS Outlook, Google [...]

What I Read This Week – 8th April - A Literal Girl — April 8, 2012

[...] The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Nathan Jurgenson at Cyborgology) the momentary popularity of the Hipstamatic-style photo serves to [...]

Lo sguardo vintage « HO DIMENTICATO L'OMBRELLO — April 9, 2012

[...] sia profana di fotografia, trovo interessante l’ articolo che ho scovato in rete The faux-vintage photo sul fenomeno della diffusione [...]

Roger — April 10, 2012

It's possible that the faux-vintage photo is a fad that will pass. Once the signifiers in play, in this case nostalgia, are brought into the light of day, they fade away. That's the point you make, and I agree. However, there may be something more enduring in the "look" of nostalgia. The imperfection of vintage photos serves to reveal and obfuscate the image. Indexically, the digital image may be too much a part of the world for viewing without discomfort, and the filter a necessary and lasting device inserted both to reveal it more slowly and remove it one step from the "real." Digital photos seen on a digital screen may not be able to exist without some form of this kind of intervention. You'll note that once printed, the digital image is able to return to its existence as a straight image.

Erwan — April 11, 2012

Long before Instagram and other smartphone apps, and even before facebook and twitter, you could already find faux-vintage photos on "art" sharing communities like deviantart and many other. With the expansion of digital photography some people were attracted to "alternative" photography with old and/or cheap cameras producing crappy happy photos (polaroïd, lomo, holgas and other lensbabies things). The photos were crappy but you could never know how they would look like and it made them so different from digital photography, always so predictable. From that point, people who did not even own a lomo camera or a polaroïd camera started to process their photos in order to make them look like photos out of old cameras.

It was when these faux-vintage photos were born and they show very well what you demonstrate, people wanted them at first to be different and they they were imitated by people seeking authenticity.

Thank you for your very interesting article and sorry for my poor english.

Erwan

The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II and III) » Cyborgology | média et société | Scoop.it — April 12, 2012

[...] background-position: 50% 0px; background-color:#222222; background-repeat : no-repeat; } thesocietypages.org - Today, 8:20 [...]

>Conseils divers< Choisir un photographe : l’importance et l’esprit du post-traitement | Amaury VIAN - Se souvenir... — April 16, 2012

[...] {j’en profite pour vous renvoyer à l’excellente réflexion de Nathan Jurgenson sur cette mode du vintage : The Faux-Vintage Photo} [...]

On time, photography, technology, and proof - A Literal Girl — April 24, 2012

[...] Manipulating time, prolonging the present, connecting with the past or the future or both, “viewing the present as increasingly a potentially documented past“, as Nathan Jurgenson writes in his essay on “The Faux-Vintage Photo”: The [...]

Past as Present | Popular Culture — April 24, 2012

[...] Vintage and retro objects and aesthetics evoke a sense of integrity and trustworthiness. This is informed by nostalgia and the vague concept of history as a simpler/better/more magical time rather than any understanding of history. This manifestation of this form of vintage appropriation can be seen in packaging that references or imitates older versions of a product or otherwise designed in a way that references past design movements, as well as in Instragram filters than transform digital photographs into something that evokes the warmth and history of vintage snapshots. (If you want to read a well-written piece on Instagram and the meaning behind pseudo-vintage photography, check out this) [...]

Black Box Tactics: The Liberatory Potential of Obscuring The Inner Workings of Technology » Cyborgology — May 7, 2012

[...] 4′s camera. You miss the detail, but the whole photo looks pretty good. And, as we all know, we are doing much more than creating an accurate visual record of events when we use our cameras. The sociologist in me is [...]

Chronique des temps modernes : argent et photographie (partie 2) | Amaury VIAN - Se souvenir... — May 26, 2012

[...] lire l’excellent essai de l’universitaire Nathan Jurgenson, en anglais, intitulé The Faux-Vintage Photo pour découvrir les raisons sous-jacentes du succès de la mode [...]

reimagining nostalgia: instacrt | THE STATE — May 26, 2012

[...] to anyone who has ever tried to take a picture of a TV screen. Nathan Jurgensen’s take on faux-vintage photo phenomenon remains ever relevant here, and is well worth a read. He suggests that this visual social mediation [...]

flybidoo — May 28, 2012

I don't know much about any of this, but have you considered these questions of authenticity/the real in light of the frankfurt school? I wonder how/if benjamin's theory of the "aura"/whatever else is in his "art in the age of mechanical reproduction" might speak to this and what you analyzed in the afghanistan piece. like i said, i have no in depth knowledge of those particular ideas (I withdrew from that particular aesthetics class ^_^), but I would love to hear your thoughts.

Picture Pluperfect « n a t h a n j u r g e n s o n — June 19, 2012

[...] may have already noticed that picturesque paintings of the past look hauntingly like the faux-vintage Instagram and Hipstamatic photos propagating social media streams today. Less a matter of capturing an accurate representation, the [...]

A New Privacy, Part 3: Documentary Consciousness » Cyborgology — July 19, 2012

[...] I term documentary consciousness, or the abstracted and internalized reproduction of others’ documentary vision. Documentary consciousness demands impossible disciplinary projects, and as such brings with it a [...]

Hipstamatic angst, Instagram anxiety: time to move the conversation forward | David Campbell — July 21, 2012

[...] that replicate earlier analogue forms have become so popular. A good place to start is with Nathan Jurgenson’s analysis of “faux-vintage” photography and the way it manifests a “nostalgia for the present.” Heightened by social media’s power to [...]

» The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II and III) » Cyborgology Maximum Vectors — July 28, 2012

[...] via The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II and III) » Cyborgology. [...]

A New Privacy: Full Essay (Parts I, II, and III) » Cyborgology — August 6, 2012

[...] I term documentary consciousness, or the abstracted and internalized reproduction of others’ documentary vision. Documentary consciousness demands impossible disciplinary projects, and as such brings with it a [...]

Cory — August 6, 2012

Damning, not damming.

-WordNerd

virtualnights Blog → Blog Archive » Das Vintage-Foto im Zeitalter seiner digitalen Reproduzierbarkeit — August 9, 2012

[...] hat bereits 2011 einen lesenswerten Aufsatz über das “gefakte Vintage-Foto” verfasst: The Faux-Vintage Photo nähert sich dem bekannten Phänomen, digitale Fotos mit Patina zu überziehen. Besonders via [...]

The Rise of Faux Vintage Photography (with the Help of Instagram) — August 14, 2012

[...] taken off? Nathan Jurgenson took that question on in a brilliant and much commented upon essay, The Faux-Vintage Photo. In it, he argues that social media plays a large part in the popularity of faux-vintage [...]

The Rise of Faux Vintage Photography (with the Help of Instagram) | Uber Patrol - The Definitive Cool Guide — August 14, 2012

[...] taken off? Nathan Jurgenson took that question on in a brilliant and much commented upon essay, The Faux-Vintage Photo. In it, he argues that social media plays a large part in the popularity of faux-vintage [...]

Stories in Focus: Visual media, style, and documentation » Cyborgology — August 25, 2012

[...] is for how we consume visual media. Nathan Jurgenson has already covered this extremely well in his essay on digital photography and the faux-vintage photo – how apps that allow one to artificially age one’s digital photos lend a sense of [...]

Apertures Matter (a brief response to ‘Stories In Focus’) » Cyborgology — August 27, 2012

[...] some of these issues surrounding the ethics of war-photographers using Hipstamatic and Instagram faux-vintage filters [...]

thef8blog: Life, cameras, passion » friday links — August 31, 2012

[...] nice essay on the whole Instagram retro look [...]

The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II and III) » Cyborgology | Hauntology | Scoop.it — September 4, 2012

[...] 'In this essay, I hope to show how faux-vintage photography, while seemingly banal, helps illustrate larger trends about social media in general. The faux-vintage photo, while getting a lot of attention in this essay, is merely an illustrative example of a larger trend whereby social media increasingly force us to view our present as always a potential documented past. But we have a ways to go before I can elaborate on that point. Some technological background is in order.' Nathan Jurgenson [...]

Laura Casarsa — September 14, 2012

very interesting essay. It is strange because today i've been to a Vintage Festval (http://wearetalkingaboutart.wordpress.com/2012/09/14/lets-vintage/) and the slogan was: don't loose THE time. I think that this use of photography through social media is a way to remember the past and look at the future in a new way.

Instagram and the Faux Vintage trend — September 19, 2012

[...] Jurgenson took that question on in a brilliant and much commented upon essay, The Faux-Vintage Photo. He argues that social media plays a large part in the popularity of faux-vintage photography, but [...]

Filtered Presents | messymethods — September 21, 2012

[...] Instagram smartphone applications. Originally posted in May 2011, Nathan Jurgenson’s essay, The Faux-Vintage Photo, describes both how these apps work visually and how they function in digital and social spaces. [...]

Hipsters and Low-Tech » Cyborgology — September 27, 2012

[...] authors have also talked about the fetishization of low-tech/analog media and devices (see: here and here). As David Paul Strohecker pointed out, these two issue interrelated: “hipsters are [...]

Hipstertechnoauthenticity » Cyborgology — September 27, 2012

[...] great interest to me: I’ve written about low-tech “striving for authenticity” in my essay on The Faux-Vintage Photo, reflected on Instagrammed war photos, the presence of old-timey cameras at Occupy Wall Street and [...]

The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II and III) » Cyborgology | Photography and society | Scoop.it — October 22, 2012

[...] [...]

The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II and III) » Cyborgology | Visual Culture and Communication | Scoop.it — October 23, 2012

[...] Look how old it looks! [...]

Initial Thoughts on Nostalgia | all these birds with teeth: this is not about science. — October 25, 2012

[...] of nostalgia by each and every person using social media, where every picture, post and link is “a potential document to be consumed by others,” which turns the present into the past, fast. Birdhead, The Song of Early Spring, [...]

Gender in League of Legends, Pt. II : ludist — October 28, 2012

[...] Nathan Jurgenson, I love talking about Instagram, so this was a pretty exciting idea for me. Plus it’s got [...]

Photopanic: Instagram and Nostalgia | messymethods — October 30, 2012

[...] exist, to create a context tied to a sense of authenticity. But, as Nathan Jurgenson argues, the nostalgia of Instagram’s faux-vintage photography is tied to a greater trend of [...]

A (Semi-)Augmented Festival: Twitter, Instagram, and Cybersociality at Iceland Airwaves 2012 » Cyborgology — November 9, 2012

[...] recent past than is the temporality of Twitter. (Instagram’s faux vintage photos encourage us to see our present as always a future past, after all, whereas Twitter invites you to “find out what’s happening, right now, with the [...]

Cabinet | Notes from 21 South Street — November 11, 2012

[...] The “indie” life is usually appropriately accompanied by photos of the fuzzy-grained, blurry-colored variety: faux-vintage photos made possible by Instagram or Hipstamatic. The phenomenon (and its implications for authenticity and nostalgia) is given analytical treatment in this three-part essay. [...]

Mel — November 28, 2012

What about the idea that we are all becoming our own curators?

Clement Greenberg would just hate this.

Let Sleeping Memories Lie: High School and the Facebookless Past » Cyborgology — November 29, 2012

[...] other words, while the documentary drive of social media may encourage us to see our present always as a future past, it also fixes our past always as a part of our present. I argue that while there is nothing new [...]

Social Media and the Arts of Memory « The Frailest Thing — December 2, 2012

[...] of this point anchored on an analysis of faux-vintage photography see Nathan Jurgenson’s, “The Faux-Vintage Photo.”) Drawing in Manovich’s database/narrative opposition further suggests that the visual/spatial [...]

new grammar | Technology as Nature — December 9, 2012

[...] matter how hard I try, I cannot understand Instagram or why anyone would use it. Why do you want to make your photos look worse? Just, why? This past winter, during an especially [...]

The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II and III) » Cyborgology | Photograph(ies) | Scoop.it — December 18, 2012

[...] Look how old it looks! [...]

Notable readings of the day 01/01/2013 « "What Are You Sinking About?" — January 1, 2013

[...] migrate across platforms and contexts in ways we don’t always see or acknowledge. Social media affects how we see the world—and how we feel about being seen in the world—even when we’re not engaged directly with [...]

Origins of the Augmented Subject » Cyborgology — January 15, 2013

[...] for social media in particular, it may constitute a subject who has both what Jurgenson calls “documentary vision” (or a “Facebook eye”) and what Whitney Erin Boesel calls “documentary [...]

Documentary Oversaturation » Cyborgology — January 28, 2013

[...] with you. I’m concerned about how social media documentation changes experience [see here, here, here, here]. I think there is good reason for why these types of documentation proliferate: [...]

Artisinal sharing and the “Like Economy” | Marginal Utility Annex — February 8, 2013

[...] idea of premediation can usefully combined with Nathan Jurgenson’s notion of “documentary vision” in social media: We are not merely interpreting our present [...]

Una nuova democrazia visiva ? « fotografia e parole — February 11, 2013

[...] oppure la mancanza della possibilità di acquisire le informazioni in formato RAW). In un bel saggio Nathan Jurgesson, tra l’altro, sottolinea come questo trend sia stato reso possibile dalla [...]

» Documentary Vision Course MCM 0230: Digital Media — February 26, 2013

[...] useful when thinking about social media. Nathan Jurgenson notes the increasing phenomenon of “documentary vision,” where “we come to see what we do as always a potential document, imploding the [...]

Pics and It Didn’t Happen | SIP — February 28, 2013

[...] colors, faded glow, and false paper scratches and borders. Instagram’s faux-vintage filters, as I argued previously, reassure that present lives are just as authentic and worthy of nostalgia as the life captured in [...]

Looking at photos | n j w v — March 4, 2013

[...] —Nathan Jurgenson, The Faux-Vintage Photo [...]

Adventures through the Google Glass « BBH Labs — March 5, 2013

[...] reasonable, inquisitive voices are raising questions about whether Google’s version of ‘documentary vision‘ is as desirable as it first appeared to be. Steve Mann, a pioneer of wearable computing, [...]

Documenting Tragedy: Vine and the Boston Marathon » Cyborgology — April 16, 2013

[...] then more people will use Vine to record tragedies and disasters when they happen. Our collective documentary vision will shift to include “shoot a vine” as a possible response to tragedies when we see [...]

The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II and III) » Cyborgology — April 23, 2013

[...] http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2011/05/14/the-faux-vintage-photo-full-essay-parts-i-ii-and-i... [...]

A Bomber’s Page One Selfie » Cyborgology — May 6, 2013

[...] to use photos that go out of their way to obscure reality with dramatic editing such as a faux-vintage filter, something I discussed when the paper ran award-winning faux-vintage war photos from [...]

The Philosophy of Instagram | Anthony Palmer — July 21, 2013

[...] Jurgenson, writing in Cyborgology, argues that our love of the “faux-vintage photo” is part of a “larger trend [...]

The Spotification Diaries » Cyborgology — September 21, 2013

[...] to come back to, because believe me: I am as floored as anyone by what some combination of Spotify, documentary vision, and I myself have done to my brain. I sometimes get cranky now when I can’t scrobble, and though [...]

The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II... — September 25, 2013

[...] Incredible 3-part post on FAUX and VINTAGE photograhy http://t.co/qjwM7sMHYU Must read! [...]