Covid-19 may be bringing long-term changes to workplaces and leisure activities as people become more attuned to potential infectious disease. But our shock, surprise, and general inability to deal with the virus also tells us something about how much our relationship with disease has changed.

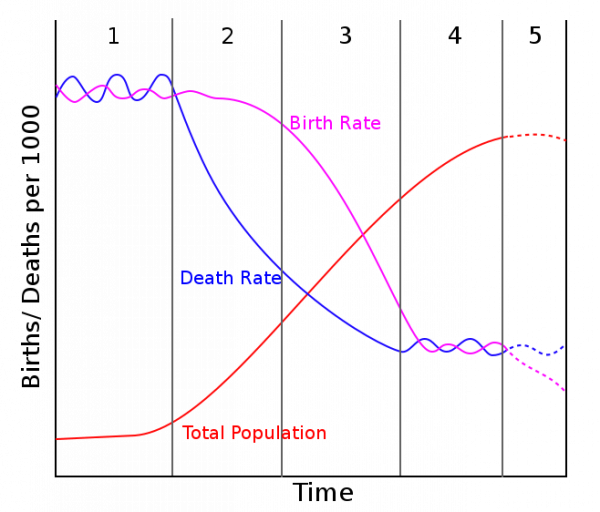

Graph showing the birth rates, death rate, and total population during each of the 5 stages of epidemiological transition. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

What scientists call the “epidemiological transition” has drastically increased the age of mortality. In other words, in the first two phases of the epidemiological transition lots of people died young, often of infection. Advancements in medicine and public health pushed the age of mortality back, and in later phases of the transition the biggest killers became degenerative diseases like heart disease and cancer. In phase four, our current phase, we have the technology to delay those degenerative diseases, and we occasionally fight emerging infections like AIDS or covid-19. Of course, local context matters, and although the general model above seems to fit the experience of many societies over a long period of time, it’s not deterministic.

- Abdel R. Omran. 1971. “The Epidemiologic Transition: A Theory of the Epidemiology of Population Change.” The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 49(4):509–38.

- David Cutler, Angus Deaton, and Adriana Lleras-Muney. 2006. “The Determinants of Mortality.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 20(3):97–120.

Inequality

Even before the epidemiological transition, not everyone had the same risk of contracting a deadly infection. Data from the urban U.S. shows that the level of mortality experienced by white Americans during the 1918 flu (a historic level considered to be a once-in-a-lifetime event by demographers), was the same level of mortality experienced by nonwhite Americans in every county in every year prior to 1918.

- James J. Feigenbaum, Christopher Muller, and Elizabeth Wrigley-Field. 2019. “Regional and Racial Inequality in Infectious Disease Mortality in US Cities, 1900-1948.” Demography 56(4):1371–88.

Rise of new infectious diseases

Clearly, as we are seeing today, the epidemiological transition isn’t a smooth line. There is also considerable year-to-year and place-to-place variability, and new diseases can cause a sharp uptick in infectious disease deaths. For instance, the emergence of AIDS in the 1980s was responsible for a rise in infectious mortality and demonstrated the need to be prepared for new diseases.

- Armstrong, G. L., L. A. Conn, and R. W. Pinner. 1999. “Trends in Infectious Disease Mortality in the United States during the 20th Century.” Journal of the American Medical Association 281(1):61–66.

In just a few short weeks, covid-19 became a leading cause of death in the United States. The pandemic is a reminder that despite all of our health advances we aren’t beyond the disruptions of infectious disease, despite the broader long-term shift from high rates of childhood mortality to high rates of degenerative disease among elders.