Europe is facing a major refugee crisis. Some nations welcome refugees, some do not. Much of the media attention is focused on how these countries are dealing with large populations fleeing from Syria. There is ongoing debate as to whether the Syrians fleeing war are “migrants” or “refugees”. We usually think “migrants” move for economic reasons, while “refugees” move during temporary political crises. Social science on the motives and meaning of migration shows a clear difference in why these two groups travel, but also how the places where they move can blur the lines between them.

Syria has faced civil unrest since 2011, when civilians took to the streets to protest against Bashar Al Assad’s regime. The unrest escalated quickly to a civil war with a total of 220,000 deaths as of January 2015. Approximately 4,000,000 Syrians have been displaced. This has ignited international conversation on the future of Syria and its refugees.

- Philippe Droz-Vincent. 2014. “‘State of Barbary’ (Take Two): From the Arab Spring to the Return of Violence in Syria.” The Middle East Journal. 68(1): 33-58

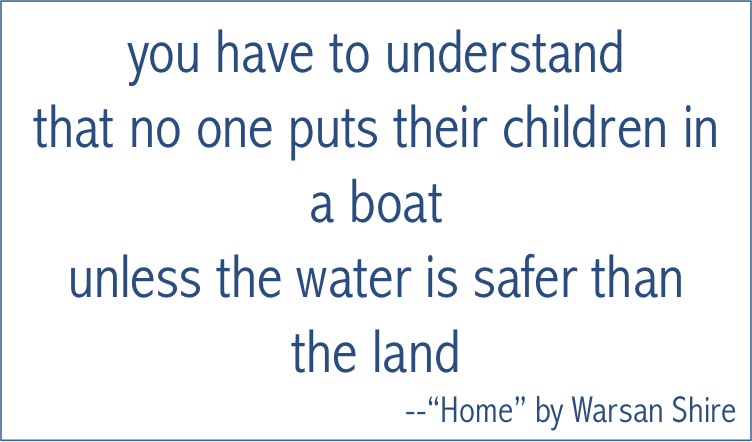

Refugees have a distinct set of reasons for leaving their home countries. In many cases, they are highly skilled workers forced out by extreme violence and social instability. They are more likely to request asylum from countries that have passed domestic refugee laws or ratified more human rights treaties than countries that are economically affluent.

- Susanne Schmeidl. 1997. “Exploring the causes of forced migration: A pooled time-series analysis, 1971-1990” Social Science Quarterly. 78(2): 284-308

- Hans Lucht. 2011. Darkness before Daybreak: African Migrants Living on the Margins in Southern Italy Today. Oakland, CA: University of California Press

- Eunhye Yoo and Jeong-Woo Koo. 2014. “Love thy neighbor: Explaining asylum seeking and hosting, 1982-2008” International Journal of Comparative Sociology. 55(1): 45-72

Refugees are looking for a society in which to build a new life, but public policy in destination nations shapes those cultural opportunities. Receiving countries often have their own foreign policy interests at heart when they decide to accept some people as refugees and deny others as migrants. These labels affect future outcomes. Studies of second-generation migrants show that they do better in countries that have many different ways to integrate new-comers, including cultural, economic, and social supports.

- Jeremy Hein. 1993. “Refugees, Immigrants, and the State.” Annual Review of Sociology 19:43-59

- Stephanie J. Nawyn. 2006. “Faith, ethnicity, and culture in refugee resettlement” American Behavioral Scientist 49(11):1509-1527

- Frank D. Bean, Susan K. Brown, James D. Bachmeier, Tineke Fokkema, and Laurence Lessard-Philips. 2012. “The dimensions and degree of second-generation incorporation in US and European cities: A comparative study of inclusion and exclusion.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology. 53(3):181-209

- Cawo M. Abdi. 2015. Elusive Jannah: The Somali Diaspora and a Borderless Muslim Identity. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press

Comments 1

Refugees and Social Instability - Treat Them Better — October 24, 2015

[…] Refugees and Social Instability […]