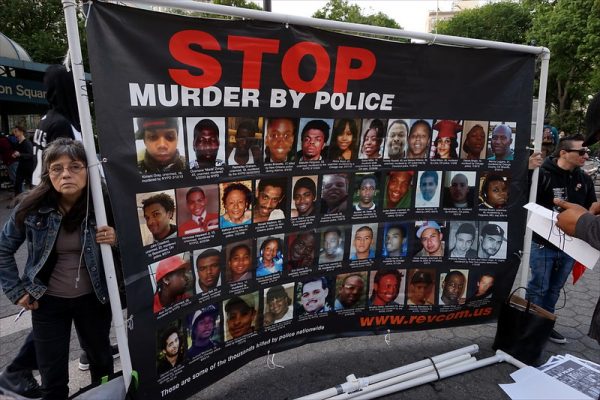

Earlier this month another Black American, Atatiana Jefferson, was fatally gunned down by a Fort Worth police officer in her own home. In the weeks since her death, community activists and residents have called for law enforcement accountability and reform of the police department’s use of force policies. As the Fort Worth community continues to grieve and fight for justice, Jefferson’s death reminds us Black women must be included in conversations around police violence, reform, and accountability. After a decades long struggle for visibility, Black women activists created the hashtag #SayHerName to bring awareness to the growing number of Black cis- and transgender women killed by law enforcement — a list Jefferson has now joined at just 28-years-old. A small but impressive group of sociological works have highlighted Black women’s experiences with police and the racialized and gendered challenges that lie ahead in developing police-community trust.

Similar to Black men and boys, Black women and girls also hold higher levels of legal cynicism (distrust) in law enforcement than whites. They report being stopped and facing verbal harassment for traffic incidents or, in the case of Black girls, breaking curfew — especially when in the presence of Black male peers. Black women and girls also distrust police due to their unresponsiveness to serious calls involving interpersonal, domestic, and sexual violence. For many Black women and girls living in low-income communities, police violence is simply one form of a larger “matrix of violence,” where they must also navigate interpersonal and neighborhood violence. At times, police are the perpetrators of these gender-specific forms of violence. These matrices remain interconnected, as cynicism towards law enforcement hinders reliance on police to address other forms of violence.

- Rod K. Brunson and Jody Miller. 2006. “Gender, Race, and Urban Policing: The Experience of African American Youths.” Gender & Society 20(4): 531-552.

- Brooklynn K. Hitchens, Patrick J. Carr, and Susan Clampet-Lundquist. 2018. “The Context for Legal Cynicism: Urban Young Women’s Experiences with Policing in Low-Income, High-Crime Neighborhoods.” Race & Justice 8(1): 27-50.

- Jennifer E. Cobbina, Michael Conteh and Collin Emrich. 2019. “Race, Gender, and Responses to the Police Among Ferguson Residents and Protesters.” Race and Justice 9(3): 276-303.

- Beth E. Richie. 2012. Arrested Justice: Black Women, Violence, and America’s Prison Nation. New York University Press.

Motherhood also brings distinct challenges that shape Black women’s attitudes towards police. Black women are targeted through “family criminalization,” where they fear law enforcement will target both their children and themselves for being “bad mothers.” Since motherhood places Black women responsible for the safety of their children, they attempt to protect Black youth from police suspicion by sharing cautionary tales, sheltering them, and teaching them to comply with police demands. Black women’s cautionary tales, however, often emphasize the police assaults against Black sons, while treating police violence against Black daughters as improbable and less violent. While Black mothers often view police as illegitimate and unresponsive, they may also use police services to help (mostly male) loved ones when other resources remain scarce.

- Sinikka Elliott and Megan Reid. 2019. “Low-Income Black Mothers Parenting Adolescents in the Mass Incarceration Era: The Long Reach of Criminalization.” American Sociological Review 84(2): 197-219.

- Shannon Malone Gonzalez. 2019. “Making It Home: An Intersectional Analysis of the Police Talk.” Gender & Society 33(3): 363-386.

- Monica Bell. 2016. “Situational Trust: How Disadvantaged Mothers Reconceive Legal Cynicism.” Law & Society Review 50(2): 314-347.