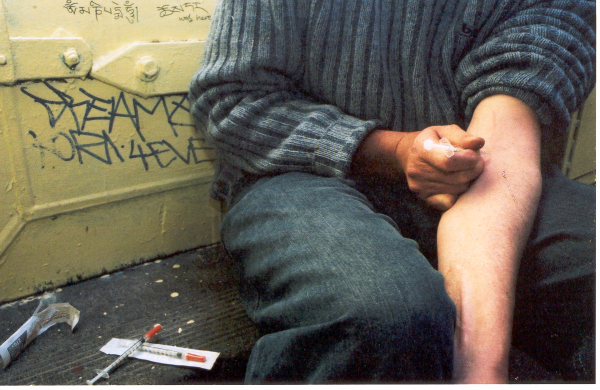

The mayor of Ithaca, New York recently proposed a facility for people to use heroin and other injected drugs safely. It’s part of a larger plan to focus on prevention and treatment of drug use, and the facility’s trained medical staff would provide clean needles, referrals to treatment programs, and naloxone, an opioid overdose antidote. Today’s opioid epidemic—which kills an estimated 78 Americans every day—has shocked many, given that other forms of illicit drug use have generally declined in prevalence and mortality during recent decades. Ithaca’s plan falls under the umbrella of “harm reduction” approaches, which attempt to mitigate personal and societal harm from drug and alcohol use. Social science shows us how and why these programs work.

Supervised injection facilities are relatively recent, originating in the Dutch and Swiss harm reduction movements of the 1970s and ‘80s. The first site in North America opened in Vancouver in 2003 and is linked to drastic declines in public injection and overdose deaths. Today a number of supervised drug consumption rooms operate throughout northern Europe, Canada, and Australia. Ithaca’s would be the first in the U.S.

- Kate Dolan et al. 2000. “Drug Consumption Facilities in Europe and the Establishment of Supervised Injecting Centres In Australia,” Drug & Alcohol Review, 19, 337-346.

Substance use was once a popular element of social events, like election day, but by the 20th century, “drug scares” stigmatized drug use, associating it with racial stereotypes, immigration, and crime. Smoking opium was first outlawed in the U.S. in the 1870s, for instance, as a result of anti-Chinese sentiments in California. Non-smoking opioid use remained popular among the white middle class—for supposed medical reasons, but by the turn of the century though, users who preferred injection became the stigmatized face of opiate addiction.

- Craig Reinarman. 1989. “Crack in Context: Politics and Media in the Making of a Drug Scare,” Contemporary Drug Problems 16(4):535-577.

-

Caroline Jean Acker. 2002. Creating the American Junkie: Addiction Research in the Classic Era of Narcotic Control. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

Stigma remains a critical issue in drug treatment, preventing users from accessing clean injection tools, uncontaminated opiates, information about safe injection practices, and life-saving overdose antidotes. Harm reduction efforts, like needle exchanges, have the potential to restore self-respect and autonomy to populations generally believed to lack these characteristics. Programs that provide work to formerly incarcerated individuals who have undergone drug treatment has been shown to reduce certain crimes, like robberies. Harm reduction communities also offer a space for drug users to empathize with and support each other, creating networks that bolster success.

- Teresa Gowan, Sarah Whetstone, and Tanja Andic. 2012. “Addiction, Agency, and the Politics of Self-Control: Doing Harm-Reduction in a Heroin Users’ Group.” Social Science and Medicine 74(8):1251-1260.

- Christopher Uggen and Sarah Shannon. 2014. “Productive Addicts and Harm Reduction: How Work Reduces Crime—But Not Drug Use.” Social Problems 61(1): 105-130.

Comments 1

neeraj — May 27, 2016

as we drug addiction will finish the human life...but Drug addiction can be cured.Although many events and cultural factors affect drug abuse trends, when youths perceive drug abuse as harmful, they reduce their drug taking. It is necessary, therefore, to help youth and the general public to understand the risks of drug abuse and for teach