The One Laptop per Child (OLPC) project, announced at the World Economic Fourm in 2005, generated a great deal of excitement at the possibility of a “wired world” where students can use new technology to develop their creative potential and analytical skills. Access to the tools provided by the project would be a boon to social and economic development in the Global South, providing kids with unprecendented developmental resources. Here’s the OLPC project’s mission statement

OLPC is not, at heart, a technology program, nor is the XO a product in any conventional sense of the word. OLPC is a non-profit organization providing a means to an end—an end that sees children in even the most remote regions of the globe being given the opportunity to tap into their own potential, to be exposed to a whole world of ideas, and to contribute to a more productive and saner world community

But the best laid plans….

The initial aim of OLPC was to provide 150 million laptops to the world’s poorest children by the end of 2008. The program has fallen far short of its original goals, or even its more modest revised goals. As of September, 2008, there were about 660,000 confirmed orders.

What happenend? An interesting analysis of the One Laptop Per Child Project done by Kenneth L. Kraemer, Jason Dedrick and Prakul Sharma at the University of California, Irvine, points the finger at too much of an emphasis on technology and not enough emphasis on the business model:

the OLPC has been stymied by its own misunderstanding of the environment in which it is operating. First, it depended on financing and distribution by host country governments, particularly educational bureaucracies that had little experience with computers in education or resources to make such investments. Second, OLPC underestimated the competitiveness of the PC industry and its willingness to undermine or co-opt any innovation that it perceives as a threat to its business model.

The report finds that the OLPC project has fallen short of its distribution goals because other actors have stepped into the low-end laptop market to provide more attractive alternatives for developing nations. That’s all right with Nicholas Negroponte, the driving force behind the project:

From my point of view, if the world were to have 30 million laptops made by competitors in the hands of children at the end of next year, that to me would be a great success. My goal is not selling laptops. OLPC is not in the laptop business. It’s in the education business.

But that might be a post-hoc rationalization of a larger failure. Initially, the operating system packaged with the OLPC systems were customized, open source-Linux based systems. The idea wasn’t intended to encourage more market activity in this area, it seems that it challenge the market model. Indeed the decision to adapt to market realities and produce OLPC systems with a Windows operating system led to the defection of a number of project members:

Some of OLPC team members like Walter Bender reportedly resigned because they believed that the inclusion of Windows was a shift away from education goals, while Krstic argued that open source purity had become more important than the educational mission to some.

The success, or lack thereof, of the $100 laptop raises interesting questions about the role open source, non-profit forms of social production play in a market economy. Should we best understand them as vehicles that identify market opportunities and then give way to the “big boys” who are motivated by market incentives? Or is there a space for an OLPC project if the logistics are handled correctly (proper integration with local cultures, distribution through non-bureaucratic channels, etc.)?

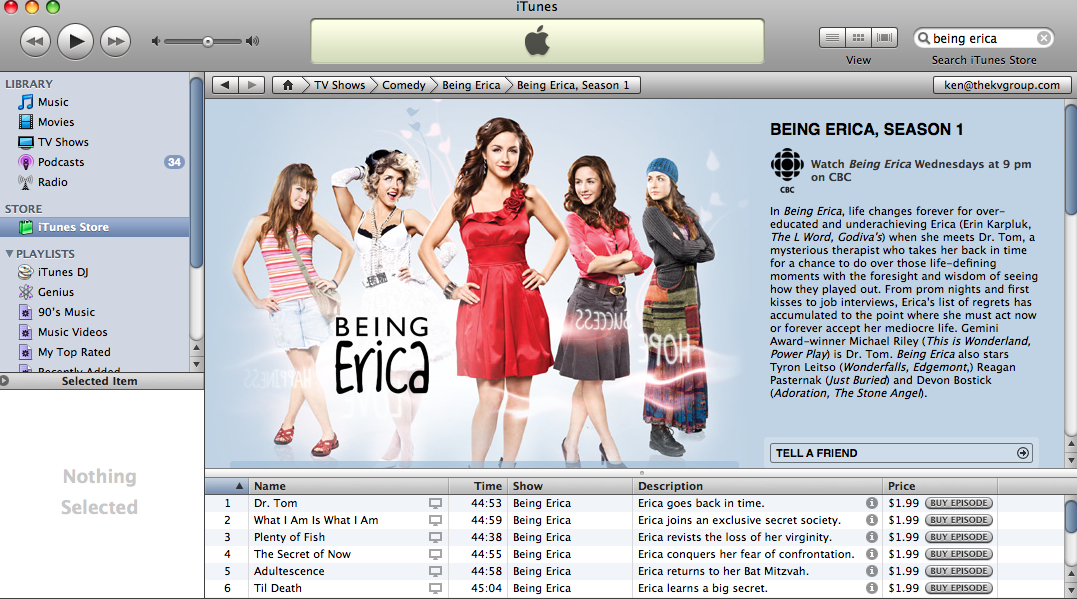

Over the holidays, I saw CBC really hyping

Over the holidays, I saw CBC really hyping