-

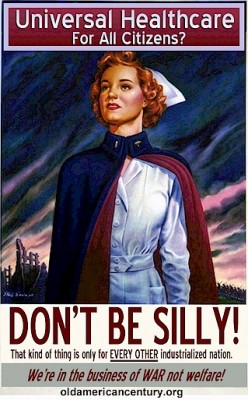

- Pointing out the obvious

Anyone curious on how how pro-single payer physicians think about the issues, I encourage you to check out the Physicians for a National Healthcare Program {PNHP} FAQ. Here’s a list of PNHP single-payer resources, as well. As stated in an earlier post, I view health care as infrastructure that can spur innovation, creativity, and entrepreneurship and like many in the biotech. industry, I see a single-payer model {public finance of healthcare, as opposed to provision} as important for implementation of genomic medicine.

I won’t go into the healthcare debate and media circus, but will link to an article on a recent NBC poll. Interestingly, 36% believe that Obama’s reform efforts are a good idea, but 53% support a paragraph describing his plans. It’s a communication problem. If you think all of the cacophony at the town halls is helping the GOP, you’re wrong. The NBC poll reports 62% disapprove of their handling of health care.

The PNHP is highly critical of the administrative costs of healthcare and are no fans of the insurance industry. Insurance also affects how healthcare providers do their jobs. I have access to hospital data that’s used to “manage care” to maximize insurance reimbursement. Moreover, there are powerful incentives in the insurance industry to maximize profits by denying claims. The PNHP recognizes that a single-payer system will adversely affect insurance::

“The new system will still need some people to administer claims. Administration will shrink, however, eliminating the need for many insurance workers, as well as administrative staff in hospitals, clinics and nursing homes. More health care providers, especially in the fields of long-term care, home health care, and public health, will be needed, and many insurance clerks can be retrained to enter these fields. Many people now working in the insurance industry are, in fact, already health professionals (e.g. nurses) who will be able to find work in the health care field again. But many insurance and health administrative workers will need a job retraining and placement program. We anticipate that such a program would cost about $20 billion, a small fraction of the administrative savings from the transition to national health insurance.”

So, shouldn’t we be concerned about insurance ? Are they getting a bad rap? Are they really evil? Isn’t it a part of financial intermediation, providing the critical function of polling resources and spreading risk?

Malcolm Gladwell in a 2005 New Yorker article did a good job of explaining two forms of insurance:: social and actuarial. Social insurance pools money from many for a public good, regardless of usage, in order to sustain an infrastructure. Actuarial insurance is quite different and has been the pathway that US healthcare has been going::

“How much you pay is in large part a function of your individual situation and history: someone who drives a sports car and has received twenty speeding tickets in the past two years pays a much higher annual premium than a soccer mom with a minivan.”

Think pre-existing conditions. The actuarial model is why biotech. wants a single-payer system. Genomics identify risks and will eventually match individuals, diseases, and therapies on the basis of genetic information. Doctors see this on the horizon and Robin Cook, MD offered this NY Times op. ed. on how he had revised his views on universal health care.

But, if you were to craft a business model, which would you choose to invest in, if you wanted to make the most profit?:: {1} social insurance that pools equal premiums from all and allocates care to all or {2} actuarial insurance that charges more for people who have a higher likelihood of becoming ill and can deny care for pre-existing conditions or treatment deemed unwarranted. The actuarial model can easily align with a set of values of individualism, as well as moral judgments about treating certain diseases {e.g., a smoker with lung cancer}. I’ve seen people on discussion boards claim that “I can take care of my own” and perplexed why everyone else cannot. How I see it, the current debates are really about using individualism to protect corporate interests. I see plenty of incentives for the actuarial insurance industry and politicians to fan the argumentative flames about wild-eyed hypotheticals, as opposed to substantive debates about implementation. The devil is in the details.

Gladwell concluded his article with the following::

“In the rest of the industrialized world, it is assumed that the more equally and widely the burdens of illness are shared, the better off the population as a whole is likely to be. The reason the United States has forty-five million people without coverage is that its health-care policy is in the hands of people who disagree, and who regard health insurance not as the solution but as the problem.”

Twitterversion:: Who will weep 4 actuarial US health insur. indstry? Are they/backers obfuscating real debates on implmntatn w/histrionics?http://url.ie/28qa @Prof_K

Song:: Pay For It – Lloyd Cole