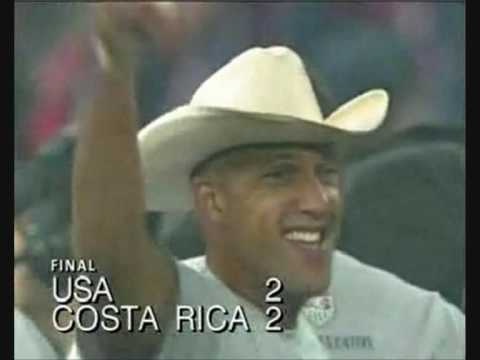

A quick explanation for the non-soccer fans: this is a recording of Honduran coverage of the U.S. v. Costa Rica game. When the U.S. scored a very late goal to tie the game, it assured Honduras’ first World Cup berth since 1982.

The recording is wonderful simply because this obviously means so much to them. It stands in contrast to the “professional” objectivity of many American commentators.

I’m currently reading through George Packer’s wonderful two volume edited collection of George Orwell essays (“Facing Unpleasant Facts: Narrative Essays” and “All Art is Propaganda: Critical Essays”). With all due respect to the erudite defaming of George Orwell in the pages of NYRB, I love the guy. I love his lucid writing. I love his courage in criticizing what he sees as wrong. I love his methodology of putting himself in the middle of things. I love his sentimentality about hearths and his homeland. Earlier this week, I read his well-known, WWII-era essay, “England Your England,” and regard it as among his very best. I believe so much of it speaks to our current state of affairs that I’d like bring some of its key points up to date. Rather than writing a full essay (which would inevitably pale in comparison), I’d like to do a little series pulling out some points of interest. This will be the first.

Orwell begins with the claim that culture differences between nations are big and meaningful: “Till recently it was thought proper to pretend that all human beings are very much alike, but in fact anyone able to use his eyes knows that the average of human behaviour differs enormously from country to country … Things that could happen in one country could not happen in another. Hitler’s June purge, for instance, could not have happened in England.”

This sort of claim remains controversial today. Browning’s Ordinary Men argued that the Holocaust wasn’t based on intrinsic characteristics of the German people, while Goldhagen’s Hitler’s Willing Executioners countered with just the opposite claim. Today, we often hear much about the immutable cultural differences between Americans and Europeans (“Americans live to work, European work to live”). Advocates of a single payer system of health care have repeatedly been told that such a system would never be accepted in the United States. Tom Friedman wrote just this Sunday about how a $1 gas tax should be, but is not up for debate in the U.S. (despite sky-high gas taxes in European countries). The mandatory religious rhetoric in any American political speech (e.g., “God Bless America”) would be the cause of scandal in Europe.

While such limitations on political speech and manner of living are profound burdens, Orwell also claims that being a member of a national culture is, ultimately, meaningful to each of us. “And above all, it is your civilization, it is you. However much you hate it or laugh at it, you will never be happy away from it for any length of time … Good or evil, it is yours, you belong to it, and this side the grave you will never get away from the marks that it has given you.”

Though we might threaten to leave (if Bush is elected in 2004) and though the vile racism and hatred and ugly nationalism at town halls and “tea party” events might disgust us, America will always feel like a home to those of us who were raised here. We breathe easier in the air we’re accustomed to. Talking loudly while eating a slice of pizza and walking down a city block, the choice of sixteen varieties of mustard in the grocery store, and the simple pleasure of a gas-guzzling muscle car and an open road are, for better or for worse, things that feel like home.

“Yes,” says Orwell, “there is something distinctive and recognizable in English civilization. It is a culture as individual as that of Spain. It is somehow bound up with solid breakfasts and gloomy Sundays, smoky towns and winding roads, green fields and red pillar-boxes. It has a flavour of its own.”

In Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell writes about the continuing legacy of the rice paddy for Asian cultures, the “culture of honor” in the American South, and the significance of hierarchy in Korean society. To be sure, our nations and our cultures constrain our behavior and even our ways of thinking. But perhaps perversely, the very culture that limits us also comforts us.

I just learned about the brilliant site Kickstarter today. On Kickstarter, artists, musicians, inventors, journalists, or whoever can post a project they want to fund. The web site encourages generous people (with disposable income) to make small contributions to the projects. A few examples:

-Two brothers need $10,000 to finish their documentary about Fred Rogers (of “Mr. Rogers Neighborhood”)

-A singer-songwriter needs $3500 to record his debut album.

-A writer needs $5000 to fund a road trip to see various examples of folk architecture for a book.

In exchange donors get rewards from the project planners. If it’s a band, maybe you’ll get a sticker for a $5 donation, a digital copy of their album for $10, and a live performance at your house for $1000. The rewards depend on the project.

It occurs to me that this would be a fantastic way to fund research. It would mean that research was conducted for which there was genuinely popular demand. Maybe the public wants an ethnography of transgendered cowboys in the rodeo circuit, but has little interest in funding a survey on TV viewing habits. It would mean research went forward that matters to people.

Heck, I’d put one of my own future projects up there for funding, but I’m not sure what rewards I can offer. What’s the limit on how many people you can thank in a journal article’s acknowledgement?

I’m ready to risk some potential embarrassment and admit my ignorance outright: I don’t understand the word “meme” — at all. I have seen the word used quite frequently (including by some TC contributors) and have read several definitions. But I just don’t get it. My hope is that some of our more erudite readers and contributors can explain it to me.

Here’s what I’ve been able to pick up so far:

-It is a widely repeated or imitated cultural idea, image, or practice.

-It supposedly acts in a manner similar to a gene, in the sense that through vast repetitions, more environmentally “fit” versions of the meme gain greater sticking power.

-With reference to the Internet, it often just means “fad.”

Some questions I have:

-Aren’t we just talking about the social reproduction of culture here — something that happens in everyday socialization?

-What is the unit of a “meme?” How does one delineate the parameters of a “meme” within a sea of culture?

-What on earth would make us think that culture is evolutionary, rather than just constantly changing without particular order?

-Isn’t the word “meme” just an attempt to make discussions of culture sound more sciencey?

As you may be aware, much of the Red River valley here along the North Dakota/Minnesota border is facing a 500 year flood set to peak on Friday. This is not a flood where lives are at risk like the one resulting from Hurricane Katrina. Nonetheless, it is a flood bigger than the 1997 flood that caused serious damage, led to displacement of hundreds of families, and drew national coverage. It is a flood that will require the placement of more than 2 million sandbags in the Fargo-Moorhead area, filled and transformed into dikes by over 10,000 volunteers yesterday alone. As a lifelong East Coaster, I am a stranger to floods. I also currently reside in a downtown apartment building and work on a campus that are both highly unlikely to be affected by flood waters. And, as a sociologist, I’m naturally inclined to view social activity with a particularly distant lens.

is facing a 500 year flood set to peak on Friday. This is not a flood where lives are at risk like the one resulting from Hurricane Katrina. Nonetheless, it is a flood bigger than the 1997 flood that caused serious damage, led to displacement of hundreds of families, and drew national coverage. It is a flood that will require the placement of more than 2 million sandbags in the Fargo-Moorhead area, filled and transformed into dikes by over 10,000 volunteers yesterday alone. As a lifelong East Coaster, I am a stranger to floods. I also currently reside in a downtown apartment building and work on a campus that are both highly unlikely to be affected by flood waters. And, as a sociologist, I’m naturally inclined to view social activity with a particularly distant lens.

So, here are a loose collection of my observations:

-My employer, Concordia College, canceled classes yesterday and today not because of any risk, but simply so that students and staff could help with the flood preparation. Moreover, the administration sent out a message on Saturday saying that all students were expected to show up at 9 am on Sunday to volunteer. Now, I’m very impressed with Concordia’s great expectations for their students, but, frankly, I’m stunned. I have great pride in my alma mater, but I know they would never, ever say that they expected (encouraged, maybe) students to do anything on a weekend –nevermind the intense manual labor of sandbagging and dike-building. I’ve been considering what might explain the difference between the two and find it difficult to say. Is it a Midwestern thing? Is it a social capital thing derived from Concordia’s status as a relatively homogeneous, Lutheran-affiliated school? Is it because Skidmore students tend to have a higher class status and approach college with a consumer model?

-The organization of sandbagging is remarkable. They have developed Sandbag Central (pictured here),

-The rhetoric of the flood and dike-building is fascinating. Though no human life is at risk, during the entire week leading up to the flood, residents have anticipated it with immense fear and growing panic. I would dare say that some of my fellow volunteers even got a pleasurable rush from the emergency scenario. On my first shuttle bus, I was seated next to a bunch of college guys (not Concordia students!) who had done shots of Jager before showing up to build dikes and had no shortage of homophobic puns about the activity. At the actual dike-building site, there was no expert or official clearly in charge, so there was hyper-masculine jostling for a leadership role. Volunteers got into minor squabbles about the proper method of laying sandbags, engaged in unnecessary demonstrations of manly strength, and attempted to out-veteran each other (“You may have been here for 1997, but let me tell you, I was here for the ’73 flood”). There was also an overwhelming sentiment that real success was achieved by common folks, not by the government. “This is how houses get saved, not by the government spending money — and that’s all they know how to do.” By contrast, I think in a similar situation in New York City, there would be much greater trust in the government, but also a sense of entitlement that it was the responsibility of the government to protect us.

-Though I can’t say I enjoyed the presence of my fellow volunteers, the strength of the community and the willingness to help unseen strangers was very inspiring. And it hearkens back to a sort of society that Robert Putnam claims died off half a century ago.

This decision was inevitable. For an Obama administration that professes to favor transparency in governance, lifting the ban on media images of soldiers’ coffins returning to Dover Air Force Base from Iraq and Afghanistan was a no-brainer. But even for the Bush administration, the ban was the most apparent example of two deeply conflicted modes of media management: secrecy at home and guided exposure abroad.

But even for the Bush administration, the ban was the most apparent example of two deeply conflicted modes of media management: secrecy at home and guided exposure abroad.

Of course, like many of the media management tactics that administration employed, the policy itself pre-dates George W. Bush’s arrival in D.C. The ban was put into place during his father’s tenure in the White House, but was never fully enforced until the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. For journalists already accustomed to the notoriously secretive ways of the second Bush administration, it was no surprise that they would deny access to such politically powerful images. Many of Bush’s advisors, including Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld, felt strongly that images of soldiers’ coffins had turned public opinion against the Vietnam War and hoped to avoid a similar result in the current conflicts. Less than a year into Bush’s first term and already known for their ability to shape media storylines with a vice-like grip on information (starkly contrasting the leaky Clinton White House), the administration officials surprised no one by restricting access.

Nonetheless, from the Pentagon’s perspective, the increased enforcement of the ban on such images marked a reversal of a larger trend. I have written elsewhere about the history of media-military relations, but, in short, military officials felt that journalists had far too much free reign in the conflicts of Vietnam and, much more recently, Somalia. Such independence, they believed, had led to largely negative coverage. In an impulsive leap to the other extreme, the Pentagon stowed journalists in pressrooms in Kuwait during the first Gulf War – an arrangement reporters and media outlets bitterly decried. For the 2003 invasion of Iraq (and to a limited extent in Afghanistan), the Pentagon introduced its controversial media embedding program, allowing journalists to attach themselves to units.

Importantly, this strategy was the exact opposite of their domestic media strategy. Rather than block media access altogether, they gave the press in-depth access to soldiers and military units, while at the same time, successfully steering them away from covering the consequences of the invasion for the civilian population. Though the embedding program was as successful a media management tactic as the secrecy in D.C., it did not breed the same sort of resentment in journalists as it provided them with fascinating (albeit one-sided) coverage. For this reason, it was the better strategy: shape the coverage, but leave them happy.

In some ways, we should question why the Bush administration didn’t reform the soldier coffin ban themselves, employing the lessons of their international media strategy with the domestic press. Rather than blocking images (which only generated more interest from the press), why didn’t the administration encourage the Pentagon to arrange sessions with vetted pro-invasion military families who would speak of the importance of the sacrifice their son or daughter made? Perhaps, they feel the image of dead Americans on U.S. soil would simply unpalatable to the American public. Returning to the current administration, the question for the future will be whether they are ushering in a legitimate age of transparency and broader media access, or if they’ve simply learned a lesson about savvy media management from their predecessors.

Last semester, a student of mine wrote a paper which followed none of the requirements of the assignment, but was fascinating nonetheless. As the result of a group project requiring students to do a content analysis of a show, he was describing the dominant values portrayed on the long-running and mediocre at best sitcom, Friends. In his paper, he quoted a 2004 reconsideration of Friends in Time magazine:

Back in 1994–that Reality Bites, Kurt Cobain year–the show wanted to explain people in their 20s to themselves: the aimlessness, the cappuccino drinking, the feeling that you were, you know, “always stuck in second gear.” It soon wisely toned down its voice-of-a-generation aspirations and became a comedy about pals and lovers who suffered comic misunderstandings and got pet monkeys. But it stuck with one theme. Being part of Gen X may not mean you had a goatee or were in a grunge band; it did, however, mean there was a good chance that your family was screwed up and that you feared it had damaged you.

This quote particularly resonated with me, despite the fact that I was 13 in 1994 and not a late 20-something. Ever since, the concept of generations has been gnawing at me. According to Strauss and Howe’s Generations, Generation Xers were born between 1961 and 1981. Defined by being the first post-Baby Boom generation, Gen X has lived in the shadow of the 60s generation and, in general, has seen less success and prosperity than their parents despite coming of age in the generally prosperous 80s and 90s. For many children of divorce in Gen. X, like the characters on Friends, they were reluctant to marry at a young age. I was born in the final year of Gen X and the cultural stuff of coffee shops, goatees, and grunge rock were aspirational — not lived experiences — for me and my peers. If Generation X’s quintessential movie is Reality Bites, Lost in Translation spoke more to people my age.

The supposed next generation, Generation Y, the Millennials, or the Net Generation, according to the wisdom of Wikipedia, were born “anywhere between the second half of the 1970s … to around the year 2000.” This huge window includes both me and my students (many of whom were born in 1990) and is not a generation to which I feel particular attachment. While I can remember life before the Internet, most of them cannot. While I was molded politically in the Clinton era (free from major foreign threat), they have come of age during Bush’s War on Terror. By most survey indicators, they are relatively more conservative and more eager to get married and reproduce than Gen. Xers.

My own relative confusion about which generation I fit into is, I think, more broadly revealing. Does anyone ever feel completely attached to the constructed identity of a generation? Is “generation” even an intellectually useful concept or should social scientists limit ourselves to the empirical measure of “age cohorts”? If, indeed, the notion of generations is useful, what might be some useful parameters for defining them?

In 1997, Malcolm Gladwell wrote a New Yorker article called “The Coolhunt” that has become something of a cult classic. In the article, he follows an employee of Converse whose sole (no pun intended) responsibility was to find “cool” people and note their style trends so that Converse could co-opt them. Gladwell argued that, in a reversal of the “trickle down” model of cultural diffusion (in which elite fashion designers ultimately decide what’s cool), we were now witnessing an era of bottom up culture.

Perhaps it’s a poor parallel, but I notice that the Blueray version of the new Dark Knight DVD allows people to “record and post user-generated commentaries over  the film using My WB Commentary.” That is to say, in addition to listening to Christopher Nolan and Christian Bale discuss the movie, listeners can create their own audio commentaries over the Internet. This new capacity seems like a natural development in the people-powered media era of YouTube, but is one with real possibilities for both art and politics (as it becomes more widely disseminated). How about a Ralph Nader commentary on Wall-E? Or Bob Woodward on Frost/Nixon? Or forget that … what about normal people having the ability to provide rich in-depth, long-form commentary on films? It seems to me to be an example of bottom-up culture that allows more meaningful discourse than most of what’s on YouTube.

the film using My WB Commentary.” That is to say, in addition to listening to Christopher Nolan and Christian Bale discuss the movie, listeners can create their own audio commentaries over the Internet. This new capacity seems like a natural development in the people-powered media era of YouTube, but is one with real possibilities for both art and politics (as it becomes more widely disseminated). How about a Ralph Nader commentary on Wall-E? Or Bob Woodward on Frost/Nixon? Or forget that … what about normal people having the ability to provide rich in-depth, long-form commentary on films? It seems to me to be an example of bottom-up culture that allows more meaningful discourse than most of what’s on YouTube.

Is anybody else excited about this technology? Am I over-estimating its potential? Is it inherently too closely controlled by corporate hands to allow for meaningful citizen commentary? Other thoughts?

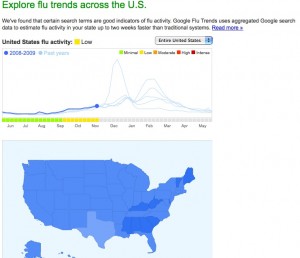

Those Google folks are just brilliant, aren’t they? In yet another moment of insight about human behavior, Google Trends has developed a map to track rises and falls in flu-related searches by location, working off the assumption that people suffering from the flu are more likely to search for information about it. One can track the total volume of flu search, study a national map of flu search trends, or enter your zip code and learn about local trends.

While it is unclear how accurately such a map can track the spread of flu, it potentially offers a powerful public health tool. I can’t get over what a clever use of search data this is.

While it is unclear how accurately such a map can track the spread of flu, it potentially offers a powerful public health tool. I can’t get over what a clever use of search data this is.

Let’s think of the next big thing! What are some other forms of internet data that (if made public) could be of great value to the public interest?

I couldn’t resist posting this as a follow-up to my previous note about the use of political culture in advertising. On my Gmail today, I saw a link that said, “Michelle Obama in J.Crew® – www.JCrew.com – Get the Look Michelle Obama Wore on The Tonight Show Only from J.Crew.” Clicking through it brought me to this page:

This is a very clever use of Michelle Obama’s mention of wearing J. Crew clothes. It seems to be capitalizing on her status as a new style icon (a la Jackie O). Also, it’s an interesting example of our gendered ideas about what products are associated with a male vs. female public figures. Somehow I don’t imagine that President-Elect Obama would be found discussing his clothes on Jay Leno or have his outfits available for purchase at popular retailers.