I was doing a post over on r h i z o m i c o n on innovation policy in Canada and also had a conversation with a future ThickCulture blogger on the future of biomedical innovation in the United States, which was the genesis of this post. I’ve been thinking about innovation policy, particularly in light of the Big Recession and the rise of global economies in places like China, India, and Brazil. Specifically, I’ve been thinking about the implications for biomedical innovation in the US, given how the pharmaceutical industry is likely to get squeezed on: {1} the demand-side {through universal healthcare being a monopsonist buyer} and {2} how public expenditures on basic science and technology are threatened, in that are deemed by some as unsustainable in the near term {due to the deficit} and the long term {due to concerns about efficiencies}.

Innovation in General

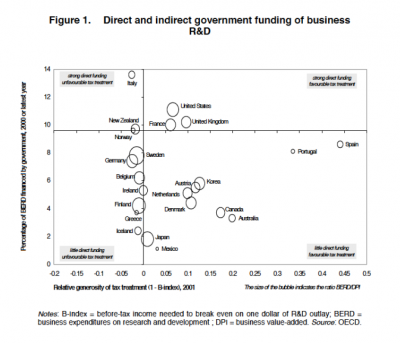

US policy has a somewhat favourable tax treatment for innovation, along with a high public expenditure contributing to business and enterprise research and development {BERD}::

While it’s fully understood the BERD is not the same as innovation, it nevertheless serves as a useful proxy measure. The sizes of the bubbles represent a measure for the productivity of BERD, with respect to value-added. The implication here is that the US government is spending a great deal on BERD and offering some tax incentives, while the outcomes aren’t that extraordinary.

As an aside, Canada’s government isn’t spending much, but offers a fairly generous tax treatment. Nevertheless, the R&D {and BERD levels} are disappointing and while some studies show some of this is due to industry effects [pdf], there are nevertheless structural issues that need to be addressed by policy, not the market alone.

Biomedical Research in the US

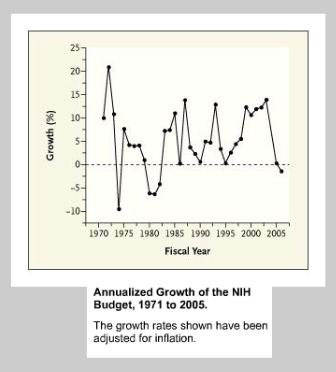

The US federal government is a big spender on health research, but these funds also go towards training and infrastructure. Historically, the funds for one of the big expenditures, the National institute for Health {NIH}, have been highly volatile::

and while the Obama administration wanted to boost funding, in order to avert a government shutdown, the great budget compromise of 2011 saw the NIH budget cut by $260M. The CDC was also cut to the tune of $730M from FY2010.

While the pharmaceutical industry invests more in R&D than the government, this represents a division of labour—the government spends on basic research, while the industry focuses on commercialization and expensive sets of clinical trials. The problem is that the governmental basic science subsidy is unlikely to be sustainable, particularly if the returns aren’t there. What I mean by returns are both in terms of value-added and health-beneffitting therapies. Under scrutiny, the lack of accountability of NIH funds and the grant practices are unlikely to show either. So, first off, reform of the NIH is in order. The current situation is leading to increased cynicism by stakeholders::

“Today, the primacy of biomedical research and technology development is being challenged. Patients, physicians, insurers, and policymakers are all questioning the slow pace of advance, escalating cost, dubious clinical value, inappropriate commercial exploitation, and lure of false hope for patients with serious diseases.”

On the pharmaceutical industry side, value-added is must likely to come from is…marketing, not biomedical science. The industry is dependent on this public subsidy, so the cutting of NIH funding isn’t in their best interests. In order to address the volatility of and cuts to NIH funding, some are advocating for more public-private partnerships and a greater reliance on non-profits and medical philanthropy. Given that the pharmaceutical industry is likely to get squeezed by universal healthcare and the possibility of less publicly-funded basic science, this sounds like a perfect solution to leverage scarce resources by both. While this sounds good, it’s a myth.

Public-Private Collaborations in the Current Biomedical Paradigm

A recent NEJM “sounding board” doesn’t show much promise for such collaborations::

“We reviewed the lessons from 70 such alliances from the mid-1960s through 2000. Although it is too soon to judge the success of the most recent models, in the main, earlier ones have not accelerated the pace of either discovery or clinical application. The sources of difficulty are idiosyncratic, but recurrent problems are a failure at inception to agree on intellectual-property provisions, excessive secrecy, and disagreements over research aims.”

This isn’t surprising at all from an organizational sociology point of view. It’s a problem of governance and intellectual property rights. The source of the failure? Good old organizational inertia, stemming from the characteristics of large, bureaucratic behemoths::

“In our view, the most salient reason for failure is the centralization of authority within large, inherently cautious bureaucracies in government, universities, foundations, and companies.”

While advances in areas such as biotechnology done by smaller innovative firms may seem like a possible avenue for collaborations and value-creation, there remains the thorny issue of financial capitalization. The pharmaceutical industry {Pharma} with its deep pockets has been buying up startup biotech firms, although it remains to be seen if there’s a pattern of imposing its innovation-killing bureaucratic baggage on them. The idea of the old paradigm {Pharma} seamlessly integrating the new {biotech} is a stretch, particularly for an industry that has had pricing carte blanche in the US, in a world of pharmaceutical price controls. Looming is the possibility of revenue declines, given that the government will be one huge buyer and will have the ability to dictate price. I’m not stating that public-private ventures are categorically bad, although I am wary of private enterprise tied to public purpose, and I can see a role for these arrangements within a rival model of innovation—one that’s open.

A More Open Innovation System

I would argue that early stage biomedical research has to be open and patents should be deferred to later in the discovery chain [See Moses III & Martin]. Locking down intellectual property rights creates knowledge silos that inhibit scientific creativity and a federal court has resisted allowing the patenting of genes for this reason [See Myriad case, on appeal with a decision pending this summer]. In the “discovery” of DNA, Watson and Crick had the theory, but Rosalind Franklin had the x-ray crystallography data that supported the idea of a double helix shape. If these knowledge silos were kept apart, discovery would have needlessly waited. Other examples abound. Within 3M, an innovation officer position was created to prevent managers from “hoarding” discoveries, allowing ideas to cross divisions, giving credit where credit was due. Open innovation embraces the Schumpeterian economics idea of “creative destruction” in innovation, where the old paradigms are destroyed to make way for the new. For example, if there was open scientific knowledge about oncology or neurology, the low barriers to information would allow for more rapid modes of discovery. The development of fruitful areas and elimination of dead ends could be facilitated.

The current mode has an unholy alignment of interests of government, industry, philanthropic nonprofits, and academe, where discovery has nothing to do with patient benefit, but with ancillary objectives of organizations and the individuals within them. More public-private ventures would merely formalize the alliances and the results will be along the lines of “innovations” that have the most profitable potential markets, “junk science” in journal articles promoting certain biomedical paradigms and building careers, and a philanthropic sector throwing money at both.

What also needs to happen with open information for innovation is a function of connecting the dots, be it public, private, or public-private. The open information needs to be scrutinized, not only to winnow the wheat from the chaff, but to make inferences about how knowledge in one area can be applied to another.

Comments 2

john — April 29, 2011

I can answer the question posed in the title very simply: no.

The avalanche of cash a few institutions have seen via tech transfer in recent years (plus Bayh-Dole) mean little-to-no open innovation.

Kenneth M. Kambara — May 6, 2011

Perkman & Walsh have an interesting paper, University–industry relationships and open innovation: Towards a research agenda offers insights into the intersection of govt. policy, organizational/institutional logics, and the management of relationships. It brings up more questions than answers, but echoes the idea that the US government is funding basic research while others, such as Germany's, support "finalization."