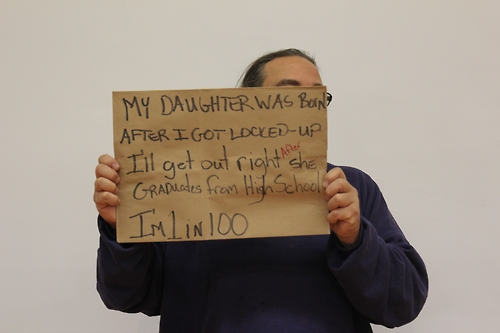

The United States is sending more and more people to prison—at an extraordinary rate compared to other western countries and our own past. U.S. incarceration rates have risen dramatically, from the imprisonment of about one hundred of every 100,000 Americans in 1970, to the imprisonment of more than 500 out of every 100,000 people in 2010.

So what? Haven’t most prisoners committed destructive crimes? Many have, of course, yet increases in imprisonment are no longer simply tracking crime rates. During the late 1970s and 1980s, incarceration rates did rise roughly in parallel to increases in crime. But crime rates have declined since 1990, while rates of incarceration have continued their upward march.

When observers express concern about “mass incarceration” or the contemporary U.S. “prison boom,” they are thinking not only of the fast-rising rates of imprisonment disconnected from crime rates. They are also worried about the disproportionate impact on racial minorities and the most economically disadvantaged Americans. Remarkably, for black men with low levels of education, going to prison is a more typical life event than attending college or entering the military.

Individual Costs and Collateral Damages

Serving time in prison hurts life chances long after a person returns to society. People with prison records find it hard to obtain jobs with good pay and prospects. Some are barred from public housing, welfare, and other social services; and in many states former inmates lose the right to vote permanently or for a long period. Throwing up so many obstacles for ex-prisoners can contribute to people committing additional offenses that take them back to prison. Recent studies suggest that as many as two-thirds of those released from prison will be re-arrested within three years. A portion of them might not have backslid if they had better prospects for normal lives.

Shrugging their shoulders, some will say that such bad consequences are merely the price of doing crime—and a proper warning to others who might go astray. But this perspective overlooks the collateral impacts on children, families, and communities. Parents make up nearly half of all those serving sentences in jails or prisons, and side-effects of their removal from families and communities must be included in our equations about costs and benefits.

Pinning Down the Costs for Families

In a series of studies, my colleagues and I have used nationally representative data to trace the family consequences of fathers’ incarceration. Using data from the Fragile Families and Child Well-Being Study, we found incarceration to be a common reason why mothers and children end up on their own without fathers in the home.

- More than 40 percent of the non-resident fathers in our data had been incarcerated at some time in their lives. Of course, there were various reasons for fathers’ absences, including misuse of alcohol and drugs and acts of physical abuse against mothers. We are not saying that fathers in prison are the only issue, but we did find that, with other factors statistically controlled, past incarcerations were significantly associated with lower levels of paternal involvement with their children.

- Not surprisingly, when men go to prison, that reduces the likelihood that parents will marry one another or live together as they raise children. In a follow-up study, we also found that current incarcerations interfered with the establishment of informal financial support agreements with mothers.

Further probing data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, my colleagues and I also found that children with incarcerated fathers are prone to negative health and behavioral outcomes.

- Youth with fathers in prison are more likely to be depressed, use marijuana and other illicit drugs, or engage in serious delinquency.

- Incarceration is passed from generation to generation, as we discovered, because children of incarcerated parents are significantly more likely to commit crimes and be sent to prison as adults.

- Do black and Hispanic children suffer more than others from having parents in prison? Our analyses find that having an incarcerated father is detrimental to all youth from every racial background. But of course more minority children are affected because their fathers are more likely to serve time.

Can America Find a New Balance?

Incarceration is far from the only challenge facing poor and minority families. They often struggle to get by in disorderly, crime-ridden neighborhoods, where many families are fragile and local institutions fall short in meeting everyday needs. What is more, arrests sometimes improve things for families and neighborhoods. Men can be dangerously abusive to their partners, and criminals put children at risk and serve as very poor role models. In our “Fragile Families” research, we found that mothers sometimes felt the need to play the role of “gatekeepers,” limiting the access of problematic fathers to their children.Yet our research also reveals unfortunate consequences for the families of many of those sent to prison. Federal, state, and local policies have contributed to rapid escalations of incarceration that are outrunning actual crime rates in many instances. Now that we understand the costly unintended consequences of mass imprisonment for many mothers and children, especially in poor minority communities, it is time to take a hard look at alternative solutions. Can we find ways consistent with public safety to punish nonviolent offenders without sending them off to prison? Are there ways to ease ex-prisoners back into full participation in family life, employment, and community affairs? Even as we look for broader solutions to the underlying economic and social conditions that foster poverty and crime, we should think of ways to mitigate the immediate and long-term costs that imprisonment can impose on innocents, including children, who are vital to America’s future.

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.