With sagging voter turnout, plummeting trust in government, and multi-billion dollar elections, U.S. democracy is marred by chasms between government and citizens. Gaps may be greatest at state and local levels, where voter turnout is especially low and citizens only rarely attend public meetings or contact local elected officials about policy decisions. Against this backdrop, communities across the country are experimenting with “participatory budgeting” – a reform that lets residents of cities, towns, and districts decide how to allocate taxpayer dollars.

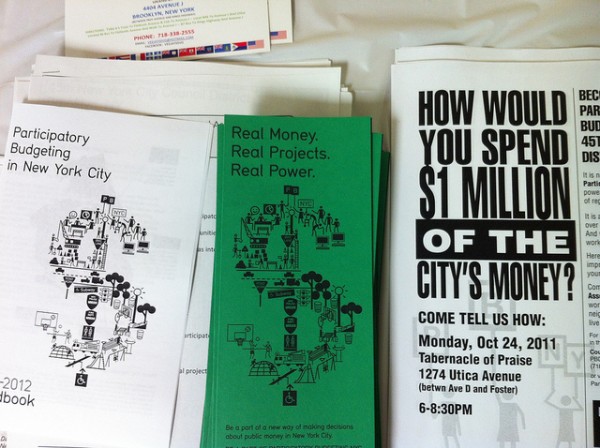

By giving communities real decision-making power in a collaborative process, participatory budgeting can strengthen ties between citizens and officials. First implemented in Brazil in 1989, it has been employed by more than 1,500 cities worldwide and made its U.S. debut in Chicago in 2009. This reform has won support from the White House and officials of all political stripes, as well as from social justice coalitions like the Right to the City Alliance.

How It Works

Months of planning are required to launch participatory budgeting. The process begins when a mayor, city council, or other authority sets aside funds for allocation – either independently or at the urging of community activists. This can happen without legal changes, but staff and financial resources must be devoted to coordination and outreach. Officials work with community groups to establish rules and set targets for public engagement. As planning proceeds, officials and community leaders often work with experts such as those involved in the Participatory Budgeting Project, a non-profit organization with which I am involved.Once established, participatory budgeting happens every year in four steps: (1) community members suggest spending ideas at public assemblies and online; (2) volunteers deliberate and work with technical experts to develop a shortlist of feasible proposals; (3) proposals are put to a public vote, often over the course of one week; and (4) the winning proposals are funded from the designated pot of public money.

As a few examples suggest, the process varies in the source of funds and types of participants:

- Vallejo, California uses city-level participatory budgeting to allocate $1 to $3 million per year from a new voter-approved sales tax to various programs, services, and public improvements. Residents 16 and older can vote, regardless of past convictions or citizenship status.

- With a focus on youth participation, Boston lets residents ages 12 to 25 decide how to allocate $1 million for city-wide public improvements.

- In 2015, New York City engaged over 51,000 residents (including young people, the undocumented, and the formerly incarcerated) in allocating $32 million in city districts – the largest participatory budgeting process in the United States.

- In Toronto, Canada public housing tenants have allocated between $5 million and $9 million annually since 2001.

The Benefits of Participatory Budgeting

No standalone reform can be a sure-fire fix for democratic woes, but international research and a growing number of U.S. studies have linked participatory budgeting to important improvements.

- Expanding participation. Tens of thousands get involved in U.S. participatory budgeting each year, including many newly engaged residents. The Community Development Project at the Urban Justice Center has data for New York showing that nearly half of participants proposing projects in 2012-2013 said they had rarely or never voted in local elections. In 2015, nearly a quarter of participatory budgeting voters reported a barrier to voting in regular elections. New York City districts also engage low-income, non-white and young participants at high rates, making participatory budgeting more representative of the entire community than local elections.

- Shifting budget priorities. Greater inclusion allows people in poor and marginalized communities to voice previously ignored needs. In Brazil, participatory budgeting has led to more funding for health services and sanitation, improving public health outcomes. A study of Chicago’s 49th Ward found that even though voters endorsed typical government projects like road repairs, they also supported funding for community gardens, murals, and playgrounds.

- Improving relations between officials and constituents. Political scientist Paolo Spada links participatory budgeting to higher reelection probabilities for local officials and their parties in Brazil. Interviews in the United States suggest similar results. For instance, Chicago Alderman Joe Moore faced a tight reelection contest in 2007, and credits his subsequent landslide victory in 2011 to participatory budgeting – arguing that collaboration with constituents increased their trust in his office. Volunteers in participatory budgeting efforts in New York, Vallejo, and Boston say they feel more connected to officials and appreciative of the complex work they do.

- Strengthening community connections. In New York’s 2013-14 cycle of participatory budgeting, 51% of voters were not members of civic or other community organizations, and two-thirds said they had never previously worked with others in their community to solve problems. According to the Great Cities Institute at the University of Illinois, Chicago has seen similar trends. In each ward, at least half of participatory budgeting voters in 2014 had not previously been involved in solving community problems. In short, previously disconnected residents come to the table, enhancing democratic capacities in communities that try participatory budgeting.

Of course, the impact of any single participatory budgeting process depends on effective design and implementation. Researchers and practitioners have learned many lessons about optimal sources and levels of funding, the organization of outreach, and the best ways to conduct meetings – as well as how to use other reforms to complement participatory budgeting. When done well, participatory budgeting shows great promise as a way to reconnect government and communities and enhance democracy in America and across the world.

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.