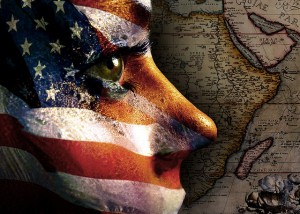

Opinions vary about whether multiculturalism and ethnic and racial diversity are divisive or beneficial to contemporary American society – but most of those discussing the issue presume that these are relatively recent trends, especially characteristic of the late-twentieth and early twenty-first century United States. The Immigration Act of 1965 is often cited as a watershed moment, a major policy change that opened the door to unusually diverse streams of immigrants, giving rise both to new ethnic, religious, and linguistic groups – and also sparking nativist reactions based on worries about a fraying national community. But a look back across U.S. history reveals that ethnic diversity and multiculturalism are hardly modern innovations.

Indeed, multicultural realities and ideals were present from the U.S. founding. Subsequent eras have brought new waves of arrivals, adding more cultures, religions, and languages into the mix, but not changing America’s core identity so much as adding to it. Only one major time period – the era between the 1920s Quota Acts and the 1965 Immigration Act – brought a temporary partial delay in the U.S. march toward greater cultural diversity.

Looking all the way back to the remarkable diversity of America’s Revolutionary era tells us much about the enduring models on which our society and national identity were grounded.

Moroccan Muslims in Revolutionary South Carolina

A Moroccan-American community lived in South Carolina during the Revolutionary era, though its exact origins are unclear. Some members had likely been brought to North America as slaves and then been freed; others may have arrived as immigrants fleeing the violence of the Barbary Pirates, encouraged to seek refuge by the 1786 Treaty of Friendship between the fledgling United States and Morocco. In any case, by 1790 the community was sizeable enough to necessitate action in the state legislature to clarify the status and citizenship of its members. A law was passed, the Moors Sundry Act, recognizing South Carolina’s Moroccan residents as “white,” thus exempting them from laws governing free or enslaved African Americans and requiring them to fulfill certain civic obligations such as jury duty.

The presence of this Muslim American population contributed to two significant statements on religion in the new nation. The only reference to religion in the body of the U.S. Constitution, Article VI, avowed that “no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office.” This provision was drafted in part by South Carolina’s Charles Pinckney, who also served as one of the authors of the Moors Sundry Act. During debates in the South Carolina about ratifying the Constitution, Pinckney unequivocally defended the “no litmus test” clause. In response to a question posed by a fellow legislator, Pinckney stated not only that the clause would allow a Muslim to run for office in the United States, but also he hoped to live to see that happen.

Early Filipino Americans in Louisiana

During this same era, Louisiana was under Spanish rule – the territory had been granted to Spain by the 1763 Treaty of Paris – and significant numbers of Spanish-speaking immigrants were arriving in the region. They came not only from Mexico but also from such far-flung Spanish colonies as the Canary Islands and the Philippines. The first Filipino arrivals created a village that came to be known as Manila Town, a settlement that has endured ever since and represents one of the nation’s oldest Asian American communities. After Louisiana was sold to the United States in 1803, Manila Town residents exercised their new American citizenship in a particularly striking way, by joining Jean Lafitte’s multi-national U.S. forces in the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812. Filipino Americans constituted a fighting unit known as the “Batarians” and helped U.S. General Andrew Jackson triumph over the British.

Chinese Americans in the 18th and 19th Centuries

Because Chinese were legally excluded from immigrating to the United States between 1882 and World War II and beyond, many people presume that Chinese Americans arrived only starting in the late 20th century. Actually, the xenophobic 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act (the first national U.S. immigration law) represented a response to a century’s worth of earlier arrivals from China. The first Chinese immigrants arrived in Spanish California in the late 18th century, and by the time the United States took control of the region in the mid-19th century there were sizeable Chinatowns in both San Francisco and Los Angeles. The 1880 census documented over 100,000 Chinese Americans, likely an underestimate. As the newly formed U.S. Republic expanded into the West, it had already encountered and incorporated significant Chinese populations.

Multiculturalism and Xenophobia

To be sure, Revolutionary-era America was defined by nativist, xenophobic fears as well as cultural diversity. Not even the most learned founders were immune to bigotry In 1751’s Observations Concerning the Increases of Mankind, Peopling of Countries, etc., Benjamin Franklin responded to German immigration into Pennsylvania by asking, “Why should the Palatine Boors [natives of a particular German region] be suffered to swarm into our Settlements, and by herding together establish their Language and Manners to the Exclusion of ours? Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a Colony of Aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them, and will never adopt our Language or Customs, any more than they can acquire our Complexion?” By the end of his life, however, Franklin repudiated his earlier views and lauded all that German Americans had contributed to Pennsylvania and the new nation. Similar sequences of fearful rejection followed by pride in diversity have followed ever since. Revolutionary-era America was defined by nativist, xenophobic fears as well as cultural diversity.Of course, contemporary U.S. society is evolving in complex ways, and cannot be understood as a mere repetition of the past. Still, a full accounting of America’s multicultural past back to the Revolutionary era shows that religious, linguistic, and ethnic diversity – and contrasting reactions to it – are nothing new. From its founding, the United States has been defined in no small measure both by sociocultural diversity and by intense conversations and conflicts about the meaning of diversity for our society, national identity, and politics.

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.