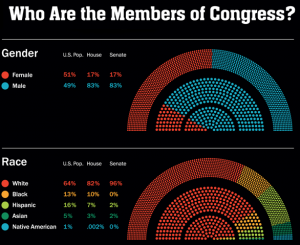

In some ways, the United States has made great progress toward including men and women from minority backgrounds in elective offices. A black president sits in the White House; the 113th Congress includes two Asian American and two Latino Senators along with 44 black and 30 Latino members of the House. More than one thousand minorities sit in state legislatures, 13 percent of the total; and the ranks of black and Latino mayors have also swelled. Yet despite this progress, gains for minorities in U.S. elective offices have failed to keep up with the presence of racial and ethnic minorities in the national population—and the shortfall is growing.

What explains this gap in representation? Since the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, social scientists have investigated minority underrepresentation from a demand perspective—that is, they have asked how the attitudes and behaviors of voters influence the chances of minority candidates to win elections and take office. However, minorities cannot win elections if they do not run, so my research also focuses on the prior, critical issue of the supply of minority candidates. To what degree is representational imbalance due to too few minority contenders?

Candidate Supply at the Start of the Pipeline

To better understand minority candidacies and electoral fortunes, I utilized data from the Local Elections in America Project gathered for the state of Louisiana between 2000 and 2010. Focusing on local municipal and school board offices, I looked to see if three sets of factors influenced, first, the supply of minority candidates and, secondly, the likelihood that minorities who chose to run for office would win. The sets of factors I investigated have been used in previous research about minority representation in U.S. elective public offices—and I had clear hypotheses about how each set of factors might affect running or winning, or both.

- Demographic characteristics of the jurisdiction. In line with past research results, for black candidates, both running and winning should be more likely in jurisdictions with more registered black voters and in communities where blacks have higher incomes and educational attainment. Previous studies have arrived at mixed conclusions about whether more liberal white voters help black candidates, but I expected such voters would influence victories rather than decisions to run by black candidates.

- Prior office holding. Given legacies of racial discrimination and intimidation, blacks may be wary of entering elections in which they would be the first to break through the racial representational barrier. Thus the supply of black candidates would be greater, I expected, for offices where blacks had previously run and held that office. Of course, I also expected that more blacks would win elections if more ran; and I expected that black newcomers, like others, would be more reluctant to run for office against a well-entrenched incumbent.

- Election timing and the offices at stake. Likelihoods of running and winning elected office are also shaped by the features of elections, and I look closely at two in particular: timing and the type (or level) of office at stake. “Off-cycle” elections not timed to coincide with statewide primaries or general contests are usually marked by much lower voter turnout, and I expected that strategically minded minorities would be less willing to run in such off-cycle elections. In addition, I expected more minorities to run for less prestigious offices such as school board or city council seats, because historically minorities have done well at winning such positions. Currently, more than nine of every ten blacks and Latinos holding U.S. elected offices are city councilors or school board members.

Running for Office versus Winning

My analysis confirms that the factors influencing minority decisions to run for office are somewhat different from the factors that determine whether minority candidates will win.- Tellingly, I found that factors known to affect minority representation—the voting strength and resources of minority constituencies and the nature of elections—actually influence running rather than winning. Many scholars have used these factors to explain wins and losses, but they are actually more important in shaping the decisions minorities make in the first stage of the process, about whether to run for office at all.

- Once minority candidates entered races, they won more than half of the elections. If I had looked only at the ultimate election outcomes, the “success rate” for black candidates would have been much lower, closer to 28 percent and below the one-third proportion of blacks in the Louisiana state population. The fundamental issue was that no black candidate chose to run at all in 60 percent of the Louisiana contests.

Winning Also Affects Decisions about Running

Much more needs to be learned about why black candidates often do not run. New research suggests that many people act strategically, avoiding races where their chances of winning seem low. Given obstacles in many past elections, black candidates contemplating public service may very well be wary of becoming the first to challenge longstanding representational barriers.

Indeed, researchers have found that the initial hurdle can be the highest; after the first attempts, it becomes easier for additional minorities to run for office. Between 2000 and 2010, the likelihood of a black candidate running was almost five times greater in jurisdictions where a black candidate had run before than in jurisdictions where it would be the first black candidacy. In addition, black incumbents are re-elected more than 60% of the time.

Overall, my research on the supply of candidates makes clear the need to recast questions about why racial minorities continue to be under-represented in U.S. elective offices. Of course, the responses of various kinds of voters to minority candidates matter. But the prior and more fundamental issue is whether minority candidates believe it is propitious to offer themselves to voters. We have much more to learn about such decisions to run, or not—and answers to these questions will suggest steps communities can take to ensure that public office-holding is open to all groups in America’s changing population.

Read more in Paru R. Shah, “It Takes a Black Candidate: A Supply-Side Theory of Minority Representation.” Political Research Quarterly 67, no. 2 (2014): 266-279.

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.