Congress is currently debating a piece of bipartisan immigration reform called the Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act. Devised by eight Senators, this proposal includes key steps to block future surges in illegal immigration. Certain provisions would reinforce militarized barriers developed in the southwest since the 1990s, while other provisions call for strengthened requirements for all U.S. businesses to use the computerized “E-Verify” system to check the legal status of applicants for jobs they offer.

Both approaches are bound to be included in any successful legislation, yet important evidence reveals why workplace enforcement is preferable. Workplace checks to prevent undocumented immigrants from taking jobs need to be refined and applied in ways that respect civil liberties. But reliance on purely militarized barriers at the border does not work as well as promised – and it pushes determined migrants into desert sectors, where hundreds die every year trying to cross into the United States.

The Roots of Border Militarization

The last grand bargain on immigration reform in 1986 aimed to strengthen border barriers. Starting in 1993 and 1994, President Bill Clinton launched beefed-up enforcement through operation “Hold the Line” in El Paso and operation “Gatekeeper” in San Diego. Similar efforts soon extended along urbanized sections of the entire border, as new fences and sophisticated surveillance systems were installed and the ranks of U.S. Border Patrol agents grew from 4000 in 1993 to more than 21,000 by 2012.

Post-1986 enforcement focused on urban areas in the hope that harsh conditions in wilderness stretches would deter illegal entries. That premise showed mixed results. Initially, determined migrants moved to cross through wilderness areas, achieving more illegal entries than ever before. Later, a weak U.S. economy and further-enhanced enforcement had some effect in discouraging attempted crossings in the mid-2000s.

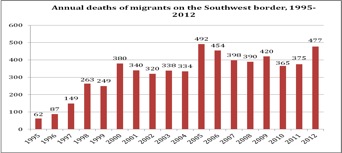

Yet available data clearly show that moderate gains in deterrence also came at escalating human cost. Facing an increasingly fortified border, migrants desperate to work or to reunite with their families in the United States take increasingly dangerous routes. Militarized enforcement has led to a spike in the number of deaths along the border – totaling nearly 6000 since 1995. Even as apprehensions have plummeted to record lows, the number of deaths remains close to record highs. On average since 2005, more than one would-be migrant has died every day.

Why Workplace Verification is a Better Way Forward

The 2013 version of immigration reform proposes even more militarized border enforcement, relying on more extensive use of the National Guard. It authorizes $3 billion for more agents and new military surveillance and detection technologies, plus an additional $1.5 billion dollars for fencing – and a possible $2 billion supplement for more manpower and infrastructure down the road. Yet “more of the same” would fail to deter all entrants while spurring more deaths.

The alternative enforcement strategy using workplace checks to cut off jobs for undocumented entrants could do more to control illegal immigration at a lower human cost. This route was not taken in 1986 because business lobbies effectively gutted employment eligibility verification. Civil and criminal penalties for hiring unauthorized workers have been weak and rarely enforced. An estimated eight million unauthorized workers hold U.S. jobs, constituting more than five percent of the national labor force. Yet between 1999 and 2011, less than one-hundredth of one-percent of U.S. employers were penalized for hiring unauthorized workers. The pending reforms could change this situation by enhancing job screening rules and requiring the use of the E-Verify employment eligibility system by all U.S. employers within five years.

We have reason to think that mandatory screening can succeed. Certain federal contractors and subcontractors plus some of the U.S. states already mandate the use of E-Verify. Other businesses also voluntarily use the system, which successfully processes more than a million eligibility queries each month. Although the existing E-Verify system is far from perfect, the U.S. Government Accountability Office has found that its accuracy improved in recent years.

Not everyone favors a turn to full job screening. Civil libertarians worry that employers will simply avoid considering “foreign-looking” applicants to avoid the hassle of possible mistakenly-flagged applicants in E-Verify. And of course many Americans are wary of any measures that involve increased government surveillance. Such reservations deserve respectful attention, but the bigger picture should also be kept in mind. Notwithstanding questions raised by skeptics of E-Verify, the potential negative consequences of enforcing immigration laws at the workplace pale in comparison to the already well-documented known cost of immigration enforcement centered mainly on building new walls on the southwestern border. That approach does more than inconvenience people; it takes a continuing grievous toll in precious human lives.

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.