To be effective, representative democracy requires that elected legislators understand what their constituents believe and want – and American politicians regularly declare that they are championing the priorities of voters in their districts. But are they? In late 2012, prior to the November elections, we surveyed nearly 2,000 candidates running for state legislative offices across the United States. Our questions were straightforward: we asked the candidates to estimate the percentage of the people in their districts who would agree that:

- same-sex marriage should be legal

- the federal government should implement a universal healthcare program

- all federal welfare programs should be abolished

We then used a large national survey and information about the characteristics of the voters in each district to estimate whether the voters truly supported each issue in each place. We found major disconnects between voters and their would-be elected representatives, and our findings raise important questions about the health of U.S. democracy and what might be done to make politics more truly representative.

A Disconnect between Legislators and Constituents

When we compare what legislators believe their constituents want to their constituents’ actual views, we discover that politicians hold remarkably inaccurate perceptions. Pick an American state legislator at random, and chances are that he or she will have massive misperceptions about district views on big-ticket issues, typically missing the mark by 15 percentage points.Pick an American state legislator at random, and chances are that he or she will have massive misperceptions about district views on big-ticket issues

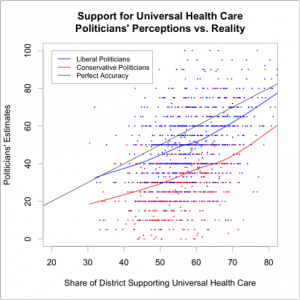

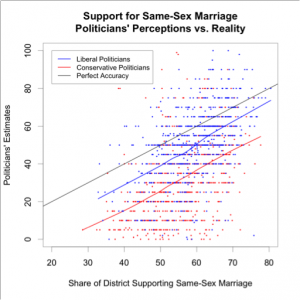

What is more, the mistakes legislators make tend to fall in one direction, giving U.S. politics a rightward tilt compared to what most voters say they want. As the following figures show, legislators usually believe their constituents are more conservative than they actually are. Our attitude measurements are most accurate on the questions about same sex marriage and universal health insurance – and in both instances the legislators’ guesses about their constituents’ views were 15-20 percent more conservative, on average, than the true public support for same-sex marriage or universal health care present in their districts.

Breaking down misperceptions by the leanings of legislators reveals further imbalances:

The typical conservative legislator overestimates his or her district’s conservatism by a whopping 20 percentage points. Indeed, he or she believes the district is even more conservative than the most right-leaning district in the entire country.- Liberals also think their constituents’ views are more conservative than they really are, but are typically only off by about five percentage points.

- Most conservative legislators believe their positions on same-sex marriage and health care command majority support in their districts – but only two-fifths are correct. In contrast, liberal legislators usually share views with constituents, but one in five does not know it.

Can Politicians Learn to Better Understand Their Constituents?

Our study also found that politicians don’t learn in the normal course of events. After November 2012, we posed the same questions again to some candidates. Even after conducting campaigns and seeing the results, politicians did not arrive at more accurate perceptions of constituent views – not even those who had spent more time talking to voters. Much remains to be learned about why U.S. legislators think constituents are more conservative than they truly are, but researchers have found that politically active citizens tend to be wealthier and more conservative than others. Politicians who want to represent all the people in their districts need to keep this in mind.

Our findings also suggest that progressive groups might be able to use a simple lobbying strategy – just let legislators know the truth about what their constituents think and want! Most of the time, legislators will discover that their constituents are more liberal than they suppose. Would that lead to policy change? It is an open question, but some research suggests that public opinion can influence what politicians do. Perhaps helping representatives perceive their constituents correctly could pave the way for public policies closer to what Americans really want.

—–

Read more in David Broockman and Christopher Skovron, “What Politicians Believe about Their Constituents: Asymmetric Misperceptions and Prospects for Constituency Control,” University of California, Berkeley, March 2013.

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.