Editor’s Note: This is the second in a series:

- Has Borrowing Replaced Earning?

- Economic Decline and the American Dream

- Old Narratives and New Realities

The 2008 – 2010 recession in the United States was the worst since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Millions of jobs were lost. Trillions of dollars in wealth evaporated. The Bush and Obama Administrations put together emergency measures designed to prevent total financial collapse with the hope that economic health would quickly return. But when social scientists take a closer look at what constitutes “economic health” for most Americans, it’s a bit like claiming your Uncle George looks “good” because he isn’t dead. The problems revealed by the recession took years to come to a head and there were plenty of signals that the American Dream was in trouble. Our troubles were covered up by the easy availability of credit that was artificially driving economic growth and middle class prosperity.

The Scale of the Problem

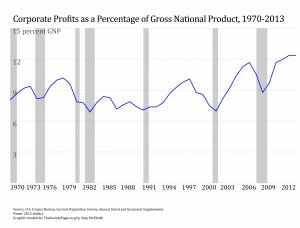

The recession numbers are staggering and the human costs incalculable. World markets lost $50 trillion in 2008 alone, roughly $8,300 for every person on earth. The U.S. lost around 7 million jobs, and the federal budget deficit is slated to hit $1.2 trillion dollars by the end of 2014. The Bush and Obama administrations assembled a bank bailout worth $770 billion and a $15 billion bailout package for Chrysler and GM, two of our “Big 3” automakers that employ hundreds of thousands of Americans. Home prices (the major source of wealth for most middle class Americans) dropped 20% in 9 years and, according to the Federal Reserve, it could take at least another decade to recover to pre-recession levels. Commercial real estate vacancies are running as high as 20% in many major cities. And consumer demand and confidence (measured monthly by the University of Michigan) haven’t been this low since the early 1970s.  The conditions of the so-called recovery may be more chilling: record high corporate profits and anemic job creation. The graphic shows corporate profits as a percentage of the Gross Domestic Product in the U.S., with shaded areas indicating recession years. While corporate profits hit another peak in 2012, job creation has been so slow that it will be many years before employment even matches 2007 levels. Steady jobs at steady wages, the very staple of middle class life, are elusive. The official unemployment rate seems to be stuck around 7%, but the more inclusive “U-6” rate is more than 13%. This includes discouraged and other “marginally attached” workers and those forced to work part-time because they can’t find full-time jobs.

The conditions of the so-called recovery may be more chilling: record high corporate profits and anemic job creation. The graphic shows corporate profits as a percentage of the Gross Domestic Product in the U.S., with shaded areas indicating recession years. While corporate profits hit another peak in 2012, job creation has been so slow that it will be many years before employment even matches 2007 levels. Steady jobs at steady wages, the very staple of middle class life, are elusive. The official unemployment rate seems to be stuck around 7%, but the more inclusive “U-6” rate is more than 13%. This includes discouraged and other “marginally attached” workers and those forced to work part-time because they can’t find full-time jobs.

Political Decision, Not Economic Inevitability

It’s unlikely that this plight is accidental. Instead, many social scientists think it’s a product of a series of political decisions made over a long period of time. Together, these decisions have rigged the economic game to favor the already affluent. For one, our tax system was changed to dramatically favor unearned income (such as capital gains) and disfavor or tax earned income (through the federal income tax, the federal payroll tax that pays for social security and Medicare, and regressive state and local taxes that take a larger percentage of the incomes of the poor and middle classes than they do the wealthy). This trend began with Reagan-era tax cuts and continued through the 2004 Bush tax cut that remains a major subject of debate. We’ve hindered the ability of workers to unionize, and union contracts set standards for the rest of the economy (regardless of whether individuals are union members). And, as the furor over Mitt Romney’s tax returns during the 2012 Presidential campaign makes clear, we’ve turned tax avoidance into a national pastime for the affluent. A once-overblown statement by the incredibly wealthy Leona Helmsley—“Taxes are only for the little people”—is now literally true.

But rigging the political game to favor the already wealthy has occurred at multiple levels, many of them unseen by average Americans going about the business of finding work and raising families. We’ve allowed affluent investors to move investments and jobs overseas to lower costs. We’ve favored investments through the tax system at the expense of earned income. Then, to make up for the revenue the Federal government doesn’t collect to pay for the programs we say we want, we’ve sold these same affluent people treasury bills at favorable interest rates to pay for what the government does, in effect a tax with a rebate attached to it (wouldn’t you like to pay taxes now and get all of your tax money back plus interest in 20 years? Sounds good to me!). We’ve allowed investors to import goods made overseas to sell to American consumers at lower prices, and, in the process of doing all of this, we’ve increased the revenues investors receive. Yet the wealthy claim to do their part as “makers” who create jobs. They loan our governments money (but skirt taxes), hire employees and build headquarters (but engage in activities that lower individual earnings), and loan consumers money (to replace lost earnings and help keep up with the middle class lifestyle). Each of these tradeoffs benefits wealthy individuals and corporations. This situation is so unfair that James Galbraith at the Lyndon Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas claims the U.S. now has three welfare states – a meagerly funded welfare state for the poor, a privately funded welfare state tied to employment for some segments of the middle class, and an interest/rent payment welfare state for the world’s wealthy.Avoiding the Issues

More interesting still is the American political system’s reaction to claims that our economic and political system is rigged to favor the already wealthy. Movements like Occupy Wall Street and “We are the 99%” have emerged to make this very point, but the response from pundits and politicians is what Scott Fitzgerald and I call “the politics of displacement.”

The politics of displacement is meeting every question about money and fairness with a screaming match about anything, anything, but money. As David Brock points out in his book The Republican Noise Machine, any topic will do: let’s talk about abortion, school prayer, flag burning, gun rights, gay marriage, fluoridated water, Sharia law in Oklahoma, or Obama’s birthplace. Anything will do so long as it distracts from talk of money and fairness. Right-wing talk radio would be nothing without the politics of displacement (I once challenged a former Republican Congressman to give an example of “mutuality” by directing me to left-wing hate radio on the AM dial—he stood in front of hundreds, flummoxed).

Many of our citizens totally buy into the politics of displacement (luckily, not as many as many pundits think). If they are going downhill, the argument goes, somebody must be to blame: blacks, Hispanics, gays, liberals, the media, or academics! The possibility that we were economically duped by the people we voted into office simply because they gave voice to our cultural prejudices doesn’t seem to occur to many.

Several reasons—obviously, they are not mutually exclusive—allow the politics of displacement to distract us. First, we allow it to happen. As voters, Americans have let our political parties and candidates avoid questions of economic fairness or deflect them in directions that lead to greater division, cynicism, and passivity. There is fighting in professional hockey because the rules permit it and it works; the same is true in politics.

Second, campaign donors and corporate sponsors are weary of politicians who want to vigorously fight social inequality. Issues of opportunity are best addressed, for this audience, as opportunities not taken, not as non-existent opportunities. Some campaign donors, like single-issue interest groups, actually play into the politics of displacement. If lots of voters are mobilized around issues that don’t involve money, presto! You can have a successful campaign, in the middle of a recession, and it won’t address money at all.

The two-party, winner-take-all political system is the third reason a politics of displacement can continue. It has produced what political commentator Kevin Phillips has long described as “the world’s most enthusiastic capitalist party” (the GOP) and “the world’s second most enthusiastic capitalist party” (the Democratic Party). Both parties make transient appeals to middle class and sometimes even poor voters, but both are funded by wealthy capitalists. The only real difference between two parties of economic elites is their acceptance of 20th century cultural trends. Democrats focus on the professional upper middle class, high-technology entrepreneurs, and other victors in the new knowledge economy, offering economic redistribution that favor a new elite and cultural ideas that alienate the middle and working classes. Republicans pitch to traditional business classes, Wall Street investors, and business elites in traditional industries, as well as those who believe there is a “culture war” in America – that moral degeneration is the major cause of declining economic prospects.

Assuming both parties will harm the average citizen’s economic picture, why wouldn’t voters go for the party that best reflects their cultural values and emotional issues? One group might give you a job and pay you a living wage, but they’re educated elites from diverse cultural backgrounds. The other group won’t give you a job at all or pay you minimum wage, but they’re white guys with families and children—they simply look more like their voter base.Fourth, the spin cycle of the media nearly demands a politics of displacement.Cable television and 24-hour talk radio need topics and conflict if they are to keep pulling the audiences their advertisers pay for. U.S. media spend endless hours delineating the virtuous “we” and the unworthy “they,” each framed as it best appeals to the outlet’s audience. Conservative media will place blame for “our” problems on “them”–every conceivable group that isn’t wealthy, white, heterosexual, or Christian. Liberal media will place blame for “our” problems on “them”—every conceivable group that isn’t highly educated, highly tolerant, and highly urban. Each insists that their representation of the divisions of American life is correct, logical, and deserving of trust. Thus, even when the outlets do strive for impartiality, they are mistrusted.

Finally, economic segregation allows for a politics of displacement. We can avoid the issues because we surround ourselves with people like us.In the U.S., economic segregation prevents us from empathizing with those who are less fortunate because they are often invisible to us. They don’t live in our part of town or we meet them as waitstaff in the low-wage service industry. “They” look like us, but we hardly realize they may be from drastically different economic circumstances than we are. Gated communities, high-rise condominiums, and suburbs have contributed mightily to this silo effect. It’s hard to care about need we can’t see. Our own needs will always seem most important until we branch out.

To their credit, some members of the press, public, and even political circles are picking up on the cynical politics of displacement, and there are hopeful signs of change on the political landscape.

Moving Forward

If much of what we’ve seen and experienced is the result of conscious political choices, the remedies must come in the form of different political choices. Many writers talk about the effect that big money, wealthy patrons, and corporate donors have on politics. The recent Citizens’ United decision that allows corporations to make political donations as if they were individuals and the recent Supreme Court decision invalidating contribution limits by individual donors certainly do not reduce the influence of the wealthy.

One way to redistribute income and continue to promote investment-based capitalism would be to widen our participation in it. Right now almost, all unearned income from interest earnings and investments is bottled up in the top 10 to 15% of the wealth distribution. The bottom half of the distribution owns nothing. Providing each child with an individual investment account at birth ($10,000 or so), managed by the government in the same way payroll tax revenues are invested, would allow the wonders of compound interest to do their work. Starting your adult life with $50,000 would mean the ability to pay off college loans, start a small business, put a down payment on a house, or move to a part of the country where there are better job opportunities. If the money isn’t needed right away, young adults could just add to their individual investment account slowly as they enter the full-time workforce. In any case, the availability of a small store of wealth from which adult life could be started would make a world of difference and cost the rest of us surprisingly little.

A second way forward requires more coordinated action. We’ve allowed our political system to substantially reward investors who speculate with our money, destroy jobs, outsource production and services, and otherwise interfere with our lives in ways that are ultimately destructive to the larger culture and community. Instead of cutting taxes on unearned incomes and then waiting for a “supply side miracle”—tax cuts that would stimulate the economy enough to bring a big windfall in revenue for the government and rising wages for everyone else—why not make the miracle explicit? Tie the capital gains tax rate on investment income to the real earnings for families of four. If real earnings move upward, capital gains tax rates go down and investors get a rebate. If real earnings stagnate or move downward, capital gains tax rates go up. If incomes remain static, capital gains tax rates continue to go up. Tying the accumulation of wealth to the economic well-being of the rest of us would alter the incentives that wealthy Americans and most investors face and, perhaps, restart the virtuous cycle of rising consumption from rising incomes.

A third way forward is for voters to pay attention to our candidates and their promises. Ask direct questions about monetary policy. Ask for clarification if we don’t understand the answers. Demand follow-through and ignore outbursts of cultural prejudice that seem like flimsy ways to redirect attention

We can afford such steps to reinvigorate the American dream. We will all be better off when we take them.

Recommended Readings

Jacob Hacker and Paul Pearson. 2010. Winner Take All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer and Turned It’s Back on the Middle Class. New York: Simon & Schuster. Tells the story of how American politics created today’s enormous economic inequalities.

Kevin T. Leicht and Scott T. Fitzgerald. 2007. Post-Industrial Peasants: The Illusion of Middle Class Prosperity. New York: Worth Publishers. Documents the recent struggles of the American middle class, drawing connections to peasants in feudal societies and sharecroppers in agrarian societies.

Katherine Porter (ed). 2012. Broke: How Debt Bankrupts the Middle Class. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. A diverse and powerful collection of research based on the 2007 Consumer Bankruptcy Project.

Comments