For a little over a year – February 2016 to March 2017 – the webzine Blackasotan published stories at the “intersection of place and race (among other things), [in order] to fill a gap and to encourage dialogue, thought, and action around the infinite manifestations of what it means to be Black in Minnesota.” In June, 2016 the site published my essay “30 Years a Minnesotan,” in which I discussed my racialized experiences over 30 years as a resident or frequent visitor to Minneapolis and St. Paul, following the first 18 years of my life in which I rarely left the southern United States. Those 30 years in Minnesota were very formative years, as my regional identity switched from southerner to midwesterner. More specifically, I began to see myself as a Minnesotan. I still identify as a Minnesotan even though I last lived there in 2013…and have now spent five years in California, after two years in Wisconsin.

I first lived in the Twin Cities in the summer of 1986 while working as a college student intern at the 3M corporate campus in the St. Paul suburb of Maplewood. Just out of high school and before I started engineering classes at Georgia Tech, I immediately noticed a different racial order than the one I knew in the south. As I detailed in the first paragraph of the my Blackasotan essay:

I grew up in mostly Black neighborhoods in the south, so spending three months in the predominantly White Minnesota Twin Cities was quite an adjustment. In fact, the first time I walked into a McDonald’s my inner voice screamed, “There are White kids working at McDonald’s!” As the summer wore on, I was shocked to see White and Asian folks in public housing complexes, and was stunned when I could count the number of Cadillacs I saw on one hand.

Toward the end of the summer I had a nasty racist encounter – an elderly White woman screamed racial slurs at me while a friend and I were stopped at a traffic light in St. Paul – but my other experiences that summer and in the three subsequent summers between academic terms at Georgia Tech were overwhelmingly positive.

When I returned to Minnesota in 1999 to become an Assistant Professor of Social Sciences in the University of Minnesota’s General College I became a permanent resident of Minneapolis. I had a both large and multiracial group of friends from the past 13 years of visits to the Twin Cities (and one weekend trip to a cabin in Nevis, MN), plus I had become fast friends with several other new faculty in the college, so I existed in a very comfortable and privileged bubble. When I became the Chair of the Department of African American & African American Studies eight years later, however, I learned much more about the landscape of race in Minneapolis, where racial inequality is extreme. As summarized in a recent Washington Post article, “the typical black family in Minneapolis earns less than half as much as the typical white family in any given year. And homeownership among black people is one-third the rate of white families. As a result, many black families have been effectively locked out of the prosperity that the city’s overwhelmingly white population enjoys.” My wife and I were well aware that we were one of the few Black families in Minneapolis’ Prospect Park neighborhood, just east of the University of Minnesota’s Minneapolis campus.

One of my first tasks as African American & African Studies department chair was to start planning the department’s 40th anniversary events, beginning in the fall of 2008. I had known that the department was started when a small group of students took over the university’s administration building in January, 1969, but I was shocked to learn that there were less than 100 Black students enrolled in the entire university at that time…out of a population of over 40,000 students. Also, few of the Black students were from the Twin Cities. I’d be stupefied if any were from Prospect Park in Southeast Minneapolis, as the city was then largely segregated, with Black families concentrated predominantly in North Minneapolis. Many African Americans today are still concentrated in that part of town.

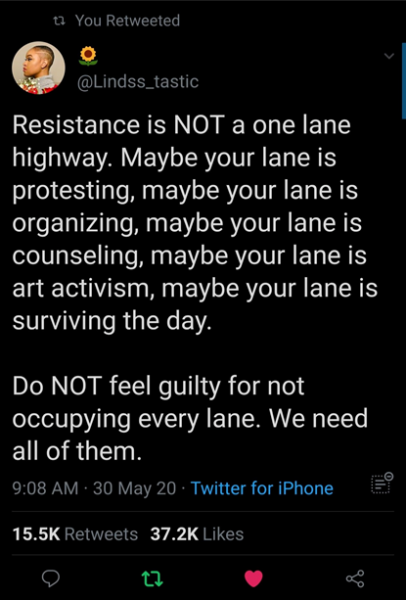

As a component of the 40th anniversary activities, we started planning an on-campus living-learning community for African American men to help us change the especially low numbers of African American men on campus. Named in honor of one of the leaders of the 1969 student occupation, Huntley House for African American Men opened in August 2012 with a goal of providing a sense of community and connectedness for African American males, and opportunities for personal and academic growth to ensure their success in college and beyond. The students regularly met with a resident advisor and a peer mentor, and engaged in both academic and social activities with faculty and other students. Huntley House is still in existence today, and has been joined by the Charlotte’s Home for Black Women living-learning community.I haven’t been in touch with members of Huntley House for a few years, but know that many of the students are from the Twin Cities. I’d imagine that while Black Lives Matter protests are raging close by their homes, some of the men might be feeling anguish over a choice to not go out into the streets to join them. They have a variety of reasons for staying inside, including not wanting to be exposed to COVID-19. If the campus were open, some of the students would also decline potential invitations to attempt to occupy administrative offices, as was done by members of their grandparents’ generation 50 years ago. I would encourage them to keep a May 20, 2020 tweet by @Lindss_tastic in mind:

In the conclusion to my Blackasotan essay I note, “[life in] the land of 10,000 lakes helped me see that there were 10,000 ways to be Black.” Indeed, there are also 10,000 ways to protest the inequality and discrimination Black people experience daily. Black Minnesotans – Blackasotans – have 10,000 lanes for creating Black identities that allow us to successfully navigate the complexities of life as Black people in America. There are 10,000 exciting paths that we can explore. Yes, we will encounter resistance on some of our journeys. For example, the 30 Years a Minnesotan essay details an incident on the University of Minnesota’s Minneapolis campus where my “authentic” Blackness was questioned when I prefaced directions to an African American couple with the “White” expression of “let’s see.” Ironically, the African American couple was traveling from North Minneapolis to Chicago Avenue, where George Floyd was murdered. Another example: the encounter I mentioned earlier about the St. Paul woman hurling racial insults at me remains to this day as the most directly racist interaction I’ve had in the 52 years of my life. Indeed, resistance Black people encounter reminds us of wretched pasts or presents, but we should expand our explorations to seek more powerful futures. Let’s go!

Oakland, CA

June 4, 2020

Return to the Wonderful/Wretched Series introduction. Next Reflection