Via Alas a Blog.

science/technology

In agriculture, monoculture is the practice of relying extensively on one crop with little biodiversity. In the 1840s, a famine in Ireland was caused by a disease that hit potatoes, the crop on which Irish people largely relied. At Understanding Evolution, an article reads:

The Irish potato clones were certainly low on genetic variation, so when the environment changed and a potato disease swept through the country in the 1840s, the potatoes (and the people who depended upon them) were devastated.

The article includes this illustration of how monocultures are vulnerable:

The Irish potato famine reveals how choices about how to feed populations, combined with biological realities, can have dramatic impacts on the world. In the three years that the famine lasted, one out of every eight Irish people died of starvation. Nearly a million emigrated to the United States, only to face poverty and discrimination, in part because of their large numbers.

The article continues:

Despite the warnings of evolution and history, much agriculture continues to depend on genetically uniform crops. The widespread planting of a single corn variety contributed to the loss of over a billion dollars worth of corn in 1970, when the U.S. crop was overwhelmed by a fungus. And in the 1980s, dependence upon a single type of grapevine root forced California grape growers to replant approximately two million acres of vines when a new race of the pest insect, grape phylloxera (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae, shown at right) attacked in the 1980s.

Gwen adds: The Irish potato famine is also an example of a reality about famines that we rarely discuss. In most famines there is food available in the country, but the government or local elites do not believe that those who are starving have any claim to that food. In the years of the Irish potato famine, British landowners continued to export wheat out of Ireland. The wheat crop wasn’t affected by the potato blight. But wheat was a commercial crop the British grew for profit. Potatoes were for Irish peasants to eat. We might think it would be obvious that when people are starving you’d make other food sources available to them, but that’s not what happened. In the social hierarchy of the time, many British elites didn’t believe that starving Irish people had a claim to their cash crop, and so they continued to ship wheat out of the country to other nations even while millions were dying or emigrating. Similarly, in the Ethiopian famines of the 1980s, the country wasn’t devoid of food; it’s just that poor rural people weren’t seen as having a right to food, and so available food was not redistributed to them. Many people in the country ate just fine while their fellow citizens starved.

So famine is often as much about politics and social hierarchies as it is about biology.

Two readers, Muriel M. M. and Lauren D., sent in this advertisement for the Oslo Gay Festival.

Three thoughts:

First, notice how the narrative reproduces the idea of the goal-oriented sentient sperm. (We’ve got a fun post on that idea here, and here’s another good one.) Remember, sperm do not have goals; they do not have ideas; they do not think. It’s just chemistry.

Second, I think it’s interesting how this video associates anal sex with gay men. How do gay men have sex? Well, they must copy straight people as closely as possible. Therefore, they must put the penis in an opening “down there.” Ah ha! I bet they all have anal sex all the time! I’m sure some gay men do have anal sex, but some surely don’t, and lots of straight couples do! I bet a lot of lesbian couples find a way to do it, too. I’m just sayin’.

Third, for what it’s worth: It also occurred to me that, in that this commercial celebrates the infertile sex act, we’ve come a long way from the Christian ethic against wasting your seed.

Political donations are by law public. With this information, someone has put up a website which shows, on google maps, which households (in the Bay Area, Salt Lake City, and Orange and L.A. Counties) donated money to Proposition 8 (California’s successful proposition to prohibit gay marriage). When you click on the arrow, it also tells you the name of the person in the household, that persons occupation and employer, and how much money they donated. Take a look.

Over at The Daily Dish, one person is quoted saying:

What could possibly be the use of this kind of information, presented in this way? It’s intended to intimidate people into not participating in politics by donating money. Do that, and you’ll end up on some activist group’s map, with hotheads being able to find your street address on their iPhones.

Andrew Sullivan weighs in:

I don’t get the fear. If Prop 8 supporters truly feel that barring equality for gay couples is vital for saving civilization, shouldn’t they be proud of their financial support? Why don’t they actually have posters advertizing their support for discriminating against gay people – as a matter of pride?

Elsewhere on the same website, a reader writes in:

I zoomed in on the cities and neighborhoods where my relatives live. What do I find but that one of my own aunts, in San Diego, contributed $200 to the Prop 8 cause last summer. This same aunt, a good person I honestly believe, has even invited me and my partner to stay with in her family’s home. Call me naive, but I’m kind of having trouble wrapping my brain around this seeming contradiction.

This back and forth raises some interesting questions:

Is the map violating some sort of privacy? If not technical, legal privacy, then some sort of cultural agreement about how far is “too far”?

Is the first commenter correct that this is essentially a nefarious act? Should political donations be public in this brave new world of google maps and internet access? Has “public” taken on a whole new meaning here?

Then again, the right to free speech protects a lot more aggressive and heinous things than this google map. Is the first commenter overreacting?

And what of Andrew Sullivan’s comment? Are those who donated proud to see themselves on the map? Or are they ashamed? When political action is unpopular (not that I’m sure this one is), does that change the nature of participation? Should holders of unpopular political beliefs be protected, perhaps by allowing them to donate anonymously? Or is shaming part of how cultural change happens and, thus, a perfectly legitimate strategy on behalf of gay rights?

Further, maybe people like the last commenter deserve to know if their friends or relatives are donating to political causes that discriminate against them? Then again, does the Aunt have any right to be able to donate to the cause without disrupting her relationships with her family?

Thoughts? Other questions you think this brings up?

Francisco (from GenderKid) sent in a cartoon that questions the benefits of the One Laptop per Child program, which aims to give a simple version of a laptop with internet access to kids in less-developed nations, and also Alabama (available at World’s Fair):

From the OLPC program’s website:

Most of the more than one billion children in the emerging world don’t have access to adequate education. The XO laptop is our answer to this crisis—and after nearly two years, we know it’s working. Almost everywhere the XO goes, school attendance increases dramatically as the children begin to open their minds and explore their own potential. One by one, a new generation is emerging with the power to change the world.

There are a number of interesting elements you might bring up here, such whether introducing laptops is necessarily the best method to improve education wordwide, or who decided that this was an important need of children in these regions (my guess is the MIT team behind OLPC didn’t go to communities and do surveys asking what local citizens would most like to see for their educational system). I recently heard a story about OLPC on NPR, and while there seemed to be benefits in some Peruvian communities, in others the teachers spent so much time trying to figure out how to use the machines to teach subjects, without really feeling comfortable with them, that almost nothing was accomplished during the day. But once the laptops were introduced, they overtook the classroom; teachers were pressured by the Peruvian government to use the laptops in almost every lesson, even if it slowed them down or it wasn’t clear that students were benefiting from them. Another problem was that, though the laptops are built to be very strong and difficult to break, on occasion of course one will break. Families must pay to repair or replace them, which of course most can’t do, meaning kids with broken laptops had to sit and watch while other kids used theirs in class.

Benjamin Cohen uses the OLPC in an engineering class and brings up concerns about…

technological determinism — [the idea] that a given technology will lead to the same outcome, no matter where it is introduced, how it is introduced, or when. The outcomes, on this impoverished view of the relationship between technology and society, are predetermined by the physical technology. (This view also assumes that what one means by “technology” is only the physical hunk of material sitting there, as opposed to including its constitutive organizational, values, and knowledge elements.) In the case of OLPC, the project assumes equal global cultural values & regional attributes. It also assumes common introduction, maintenance, educational (as in learning styles and habits), and image values everywhere in the world. Furthermore, it lives in a historical vacuum assuming that there is no history in the so-called “developing world” for shiny, fancy things from the West dropped in, The-Gods-Must-Be-Crazy style, from the sky.

How could the same laptop have the same meaning and value in, say, Nigeria and Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and Alabama, Malawi and Mongolia?

These critiques aren’t to say there is no value in OLPC, but that there are some clear questions about whether this is the most effective way to improve education in impoverished or isolated communities and what its consequences are. I doubt the OLPC creators meant for teachers to face government pressure to use the laptops for every lesson, no matter what, but that’s what has happened in at least some areas.

Another problem the NPR story highlighted was that the kids they reported about in Peru live in areas where there are absolutely no jobs available to capitalize on their tech skills, nor any reason to believe there will be any time soon. The government is pushing laptops in education, but without any economic development program to bring jobs to the regions to take advantage of these educated students. So the question is, after you get your laptop, you learn how to use it, you graduate…then what? Will the laptops spur more brain drain and out-migration? Is this necessarily good? Are countries like Peru using the laptop program as a quick, flashy substitute for the more boring, difficult, challenging process of economic development and job creation? As an educator, I’m thrilled with the idea of valuing learning and knowledge for its own sake, but on a more practical level, these questions seem like important ones.

Thanks, Francisco!

UPDATE: In a comment, Sid says,

…there’s kind of a vaguely imperialistic nostalgia in the first image of “Darkest Africa” as a simpler, more wholesome place where kids still play together in front of the hut and there’s a sense of community that you just don’t get in the modern world and blahdee blahdee blah. The entire thing kind of smacks of a whitemansburden.org enterprise…

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.

Beth sent in a link to WowWee, a company that makes robot toys, including Robosapien:

The description of Robosapien:

Robosapien™ is a sophisticated fusion of technology and personality. Loaded with attitude and intelligence, Robosapien is the first robot based on the science of applied biomorphic robotics. With a full range of dynamic motion, interactive sensors and a unique personality, Robosapien is more than a mechanical companion — he’s a multi-functional, thinking, feeling robot with attitude!

There is also a female version, called Femisapien:

From the website:

Intelligent and interactive, RS Femisapien™ speaks her own language called “emotish” which consists of gentle sounds and gestures. There is no remote required; interact with her directly and she responds to your hand gestures, touch, and sound.

So the default robot is male, with the female being not a female Robosapien but rather an entirely different product. And the photos and descriptions of Robosapien emphasize aggression, movement, personality, and “attitude,” while Femisapien speaks “emotish” (seriously?), which is “gentle”–a characteristic that seems to be missing from Robosapien, who is dynamic and, um, maybe shoots lasers from his hands.

It’s a nice example of gendered assumptions being built into product design and marketing. There’s no particular reason that the male and female versions of a robot have to look so very different, but even if they did, the decision to associate one with words and characteristics that evoke emotion and gentleness and the other with aggression and movement isn’t accidental; it’s a result of how we think about males and females.

For another excellent example of the men are people and women are women thing, see this post on the Body Worlds exhibit.

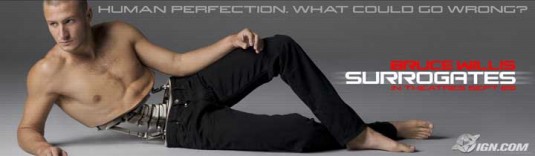

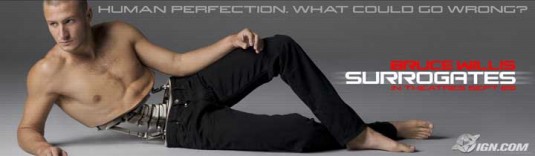

NEW! Kyle M. sent us a link to his post on the advertising for the sci-fi show Surrogates. He makes some great observations. I noticed, too, that the way in which the robotic components of men and women were designed differed slightly in gendered ways. The “spines” of the men are significantly more robust than the thin, spindly spines given to the female characters. Notice, also, that the way in which the models are posed emphasizes women’s thinness (in all of these ads, she is positioned sideways, minimizing her size) and men’s broadness (positioned so that the width of his body is emphasized).

Freud distinguished between a “mature” (vaginal) and “immature” (clitoral) orgasm, telling women that to require clitoral stimulation for orgasm was a psychological problem. Contesting this, in 1970 Anne Koedt wrote The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm. She explains:

Frigidity has generally been defined by men as the failure of women to have vaginal orgasms. Actually the vagina is not a highly sensitive area and is not constructed to achieve orgasm. It is the clitoris which is the center of sexual sensitivity and which is the female equivalent of the penis… Rather than tracing female frigidity to the false assumptions about female anatomy, our “experts” have declared frigidity a psychological problem of women.

Indeed, studies show that about 1/3rd of women regularly reach orgasm during penile-vaginal sex. The rest (that is, the majority) require more direct clitoral stimulation. Koedt goes on (my emphasis):

All this leads to some interesting questions about conventional sex and our role in it. Men have orgasms essentially by friction with the vagina, not the clitoral area, which is external and not able to cause friction the way penetration does. Women have thus been defined sexually in terms of what pleases men; our own biology has not been properly analyzed. Instead, we are fed the myth of the liberated woman and her vaginal orgasm – an orgasm which in fact does not exist.

Koedt’s article was highly influential and rejecting the notion of the “vaginal orgasm” (both anatomically and functionally) was part of second wave feminism.

Still, the vaginal orgasm keeps coming back. During the ’90s, it came back in the form of the G-spot. You, too, can have a vaginal orgasm if you can just find that totally-orgasmic-pleasure-spot-rich-in-blood-vessels-and-nerve-endings-that-makes-for-wildly-amazing-orgasms-with-ejaculation that you, strangely, never knew was there! (See what Betty Dodson has to say about the g-spot here.)

Most recently, the vaginal orgasm has come back in the form of orgasmic birth. The idea is that women can, if they really want to, have an orgasm (or orgasms) during childbirth.

Now, I don’t want to argue that women never have orgasms from penile-vaginal intercourse. They do. I also don’t care to debate whether a g-spot exists. And I am certainly not going to look a mother in the face and tell her she did not have an orgasm during childbirth. I am sure some women do. (And, anyway, I get a kick out of thinking about such a mother telling her teenager the story of his birth, so I’m going to keep believing it is true).

Anyway, what I do want to do is discuss how the video below uses the idea of orgasmic birth to reinscribe the myth of the vaginal orgasm. The reporter says that orgasmic birth is just “basic science” and then turns to interview an M.D. The M.D. uses the vaginal orgasm as scientific evidence for the possibility of orgasmic birth. She says: obviously a baby would cause an orgasm when it comes out the vagina, since a penis causes an orgasm when it goes into the vagina. But, of course, it usually doesn’t. That last part isn’t “basic science,” it’s ideology (as Koedt so nicely points out).

I wonder how many women now feel doubly bad. Not only can they not have orgasms from penile-vaginal intercourse, they also experienced pain during childbirth! Bad ladies! Watch the whole 8-minute clip or start at 3:28 to see the interview with the M.D.:

Via Jezebel.

Simon O., who sent in this ad for high-speed internet, tells us that the text reads “just suck it down.” He also tells us that the Austrian government pulled the plug (so to speak) on this advertisement.

But seriously… there is good evidence that pornography has driven a great deal of the innovation in communication techology since… well, since communication technology existed. Here’s a Guardian article on how it’s doing so even now.

In agriculture, monoculture is the practice of relying extensively on one crop with little biodiversity. In the 1840s, a famine in Ireland was caused by a disease that hit potatoes, the crop on which Irish people largely relied. At Understanding Evolution, an article reads:

The Irish potato clones were certainly low on genetic variation, so when the environment changed and a potato disease swept through the country in the 1840s, the potatoes (and the people who depended upon them) were devastated.

The article includes this illustration of how monocultures are vulnerable:

The Irish potato famine reveals how choices about how to feed populations, combined with biological realities, can have dramatic impacts on the world. In the three years that the famine lasted, one out of every eight Irish people died of starvation. Nearly a million emigrated to the United States, only to face poverty and discrimination, in part because of their large numbers.

The article continues:

Despite the warnings of evolution and history, much agriculture continues to depend on genetically uniform crops. The widespread planting of a single corn variety contributed to the loss of over a billion dollars worth of corn in 1970, when the U.S. crop was overwhelmed by a fungus. And in the 1980s, dependence upon a single type of grapevine root forced California grape growers to replant approximately two million acres of vines when a new race of the pest insect, grape phylloxera (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae, shown at right) attacked in the 1980s.

Gwen adds: The Irish potato famine is also an example of a reality about famines that we rarely discuss. In most famines there is food available in the country, but the government or local elites do not believe that those who are starving have any claim to that food. In the years of the Irish potato famine, British landowners continued to export wheat out of Ireland. The wheat crop wasn’t affected by the potato blight. But wheat was a commercial crop the British grew for profit. Potatoes were for Irish peasants to eat. We might think it would be obvious that when people are starving you’d make other food sources available to them, but that’s not what happened. In the social hierarchy of the time, many British elites didn’t believe that starving Irish people had a claim to their cash crop, and so they continued to ship wheat out of the country to other nations even while millions were dying or emigrating. Similarly, in the Ethiopian famines of the 1980s, the country wasn’t devoid of food; it’s just that poor rural people weren’t seen as having a right to food, and so available food was not redistributed to them. Many people in the country ate just fine while their fellow citizens starved.

So famine is often as much about politics and social hierarchies as it is about biology.

Two readers, Muriel M. M. and Lauren D., sent in this advertisement for the Oslo Gay Festival.

Three thoughts:

First, notice how the narrative reproduces the idea of the goal-oriented sentient sperm. (We’ve got a fun post on that idea here, and here’s another good one.) Remember, sperm do not have goals; they do not have ideas; they do not think. It’s just chemistry.

Second, I think it’s interesting how this video associates anal sex with gay men. How do gay men have sex? Well, they must copy straight people as closely as possible. Therefore, they must put the penis in an opening “down there.” Ah ha! I bet they all have anal sex all the time! I’m sure some gay men do have anal sex, but some surely don’t, and lots of straight couples do! I bet a lot of lesbian couples find a way to do it, too. I’m just sayin’.

Third, for what it’s worth: It also occurred to me that, in that this commercial celebrates the infertile sex act, we’ve come a long way from the Christian ethic against wasting your seed.

Political donations are by law public. With this information, someone has put up a website which shows, on google maps, which households (in the Bay Area, Salt Lake City, and Orange and L.A. Counties) donated money to Proposition 8 (California’s successful proposition to prohibit gay marriage). When you click on the arrow, it also tells you the name of the person in the household, that persons occupation and employer, and how much money they donated. Take a look.

Over at The Daily Dish, one person is quoted saying:

What could possibly be the use of this kind of information, presented in this way? It’s intended to intimidate people into not participating in politics by donating money. Do that, and you’ll end up on some activist group’s map, with hotheads being able to find your street address on their iPhones.

Andrew Sullivan weighs in:

I don’t get the fear. If Prop 8 supporters truly feel that barring equality for gay couples is vital for saving civilization, shouldn’t they be proud of their financial support? Why don’t they actually have posters advertizing their support for discriminating against gay people – as a matter of pride?

Elsewhere on the same website, a reader writes in:

I zoomed in on the cities and neighborhoods where my relatives live. What do I find but that one of my own aunts, in San Diego, contributed $200 to the Prop 8 cause last summer. This same aunt, a good person I honestly believe, has even invited me and my partner to stay with in her family’s home. Call me naive, but I’m kind of having trouble wrapping my brain around this seeming contradiction.

This back and forth raises some interesting questions:

Is the map violating some sort of privacy? If not technical, legal privacy, then some sort of cultural agreement about how far is “too far”?

Is the first commenter correct that this is essentially a nefarious act? Should political donations be public in this brave new world of google maps and internet access? Has “public” taken on a whole new meaning here?

Then again, the right to free speech protects a lot more aggressive and heinous things than this google map. Is the first commenter overreacting?

And what of Andrew Sullivan’s comment? Are those who donated proud to see themselves on the map? Or are they ashamed? When political action is unpopular (not that I’m sure this one is), does that change the nature of participation? Should holders of unpopular political beliefs be protected, perhaps by allowing them to donate anonymously? Or is shaming part of how cultural change happens and, thus, a perfectly legitimate strategy on behalf of gay rights?

Further, maybe people like the last commenter deserve to know if their friends or relatives are donating to political causes that discriminate against them? Then again, does the Aunt have any right to be able to donate to the cause without disrupting her relationships with her family?

Thoughts? Other questions you think this brings up?

Francisco (from GenderKid) sent in a cartoon that questions the benefits of the One Laptop per Child program, which aims to give a simple version of a laptop with internet access to kids in less-developed nations, and also Alabama (available at World’s Fair):

From the OLPC program’s website:

Most of the more than one billion children in the emerging world don’t have access to adequate education. The XO laptop is our answer to this crisis—and after nearly two years, we know it’s working. Almost everywhere the XO goes, school attendance increases dramatically as the children begin to open their minds and explore their own potential. One by one, a new generation is emerging with the power to change the world.

There are a number of interesting elements you might bring up here, such whether introducing laptops is necessarily the best method to improve education wordwide, or who decided that this was an important need of children in these regions (my guess is the MIT team behind OLPC didn’t go to communities and do surveys asking what local citizens would most like to see for their educational system). I recently heard a story about OLPC on NPR, and while there seemed to be benefits in some Peruvian communities, in others the teachers spent so much time trying to figure out how to use the machines to teach subjects, without really feeling comfortable with them, that almost nothing was accomplished during the day. But once the laptops were introduced, they overtook the classroom; teachers were pressured by the Peruvian government to use the laptops in almost every lesson, even if it slowed them down or it wasn’t clear that students were benefiting from them. Another problem was that, though the laptops are built to be very strong and difficult to break, on occasion of course one will break. Families must pay to repair or replace them, which of course most can’t do, meaning kids with broken laptops had to sit and watch while other kids used theirs in class.

Benjamin Cohen uses the OLPC in an engineering class and brings up concerns about…

technological determinism — [the idea] that a given technology will lead to the same outcome, no matter where it is introduced, how it is introduced, or when. The outcomes, on this impoverished view of the relationship between technology and society, are predetermined by the physical technology. (This view also assumes that what one means by “technology” is only the physical hunk of material sitting there, as opposed to including its constitutive organizational, values, and knowledge elements.) In the case of OLPC, the project assumes equal global cultural values & regional attributes. It also assumes common introduction, maintenance, educational (as in learning styles and habits), and image values everywhere in the world. Furthermore, it lives in a historical vacuum assuming that there is no history in the so-called “developing world” for shiny, fancy things from the West dropped in, The-Gods-Must-Be-Crazy style, from the sky.

How could the same laptop have the same meaning and value in, say, Nigeria and Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and Alabama, Malawi and Mongolia?

These critiques aren’t to say there is no value in OLPC, but that there are some clear questions about whether this is the most effective way to improve education in impoverished or isolated communities and what its consequences are. I doubt the OLPC creators meant for teachers to face government pressure to use the laptops for every lesson, no matter what, but that’s what has happened in at least some areas.

Another problem the NPR story highlighted was that the kids they reported about in Peru live in areas where there are absolutely no jobs available to capitalize on their tech skills, nor any reason to believe there will be any time soon. The government is pushing laptops in education, but without any economic development program to bring jobs to the regions to take advantage of these educated students. So the question is, after you get your laptop, you learn how to use it, you graduate…then what? Will the laptops spur more brain drain and out-migration? Is this necessarily good? Are countries like Peru using the laptop program as a quick, flashy substitute for the more boring, difficult, challenging process of economic development and job creation? As an educator, I’m thrilled with the idea of valuing learning and knowledge for its own sake, but on a more practical level, these questions seem like important ones.

Thanks, Francisco!

UPDATE: In a comment, Sid says,

…there’s kind of a vaguely imperialistic nostalgia in the first image of “Darkest Africa” as a simpler, more wholesome place where kids still play together in front of the hut and there’s a sense of community that you just don’t get in the modern world and blahdee blahdee blah. The entire thing kind of smacks of a whitemansburden.org enterprise…

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.

Beth sent in a link to WowWee, a company that makes robot toys, including Robosapien:

The description of Robosapien:

Robosapien™ is a sophisticated fusion of technology and personality. Loaded with attitude and intelligence, Robosapien is the first robot based on the science of applied biomorphic robotics. With a full range of dynamic motion, interactive sensors and a unique personality, Robosapien is more than a mechanical companion — he’s a multi-functional, thinking, feeling robot with attitude!

There is also a female version, called Femisapien:

From the website:

Intelligent and interactive, RS Femisapien™ speaks her own language called “emotish” which consists of gentle sounds and gestures. There is no remote required; interact with her directly and she responds to your hand gestures, touch, and sound.

So the default robot is male, with the female being not a female Robosapien but rather an entirely different product. And the photos and descriptions of Robosapien emphasize aggression, movement, personality, and “attitude,” while Femisapien speaks “emotish” (seriously?), which is “gentle”–a characteristic that seems to be missing from Robosapien, who is dynamic and, um, maybe shoots lasers from his hands.

It’s a nice example of gendered assumptions being built into product design and marketing. There’s no particular reason that the male and female versions of a robot have to look so very different, but even if they did, the decision to associate one with words and characteristics that evoke emotion and gentleness and the other with aggression and movement isn’t accidental; it’s a result of how we think about males and females.

For another excellent example of the men are people and women are women thing, see this post on the Body Worlds exhibit.

NEW! Kyle M. sent us a link to his post on the advertising for the sci-fi show Surrogates. He makes some great observations. I noticed, too, that the way in which the robotic components of men and women were designed differed slightly in gendered ways. The “spines” of the men are significantly more robust than the thin, spindly spines given to the female characters. Notice, also, that the way in which the models are posed emphasizes women’s thinness (in all of these ads, she is positioned sideways, minimizing her size) and men’s broadness (positioned so that the width of his body is emphasized).

Freud distinguished between a “mature” (vaginal) and “immature” (clitoral) orgasm, telling women that to require clitoral stimulation for orgasm was a psychological problem. Contesting this, in 1970 Anne Koedt wrote The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm. She explains:

Frigidity has generally been defined by men as the failure of women to have vaginal orgasms. Actually the vagina is not a highly sensitive area and is not constructed to achieve orgasm. It is the clitoris which is the center of sexual sensitivity and which is the female equivalent of the penis… Rather than tracing female frigidity to the false assumptions about female anatomy, our “experts” have declared frigidity a psychological problem of women.

Indeed, studies show that about 1/3rd of women regularly reach orgasm during penile-vaginal sex. The rest (that is, the majority) require more direct clitoral stimulation. Koedt goes on (my emphasis):

All this leads to some interesting questions about conventional sex and our role in it. Men have orgasms essentially by friction with the vagina, not the clitoral area, which is external and not able to cause friction the way penetration does. Women have thus been defined sexually in terms of what pleases men; our own biology has not been properly analyzed. Instead, we are fed the myth of the liberated woman and her vaginal orgasm – an orgasm which in fact does not exist.

Koedt’s article was highly influential and rejecting the notion of the “vaginal orgasm” (both anatomically and functionally) was part of second wave feminism.

Still, the vaginal orgasm keeps coming back. During the ’90s, it came back in the form of the G-spot. You, too, can have a vaginal orgasm if you can just find that totally-orgasmic-pleasure-spot-rich-in-blood-vessels-and-nerve-endings-that-makes-for-wildly-amazing-orgasms-with-ejaculation that you, strangely, never knew was there! (See what Betty Dodson has to say about the g-spot here.)

Most recently, the vaginal orgasm has come back in the form of orgasmic birth. The idea is that women can, if they really want to, have an orgasm (or orgasms) during childbirth.

Now, I don’t want to argue that women never have orgasms from penile-vaginal intercourse. They do. I also don’t care to debate whether a g-spot exists. And I am certainly not going to look a mother in the face and tell her she did not have an orgasm during childbirth. I am sure some women do. (And, anyway, I get a kick out of thinking about such a mother telling her teenager the story of his birth, so I’m going to keep believing it is true).

Anyway, what I do want to do is discuss how the video below uses the idea of orgasmic birth to reinscribe the myth of the vaginal orgasm. The reporter says that orgasmic birth is just “basic science” and then turns to interview an M.D. The M.D. uses the vaginal orgasm as scientific evidence for the possibility of orgasmic birth. She says: obviously a baby would cause an orgasm when it comes out the vagina, since a penis causes an orgasm when it goes into the vagina. But, of course, it usually doesn’t. That last part isn’t “basic science,” it’s ideology (as Koedt so nicely points out).

I wonder how many women now feel doubly bad. Not only can they not have orgasms from penile-vaginal intercourse, they also experienced pain during childbirth! Bad ladies! Watch the whole 8-minute clip or start at 3:28 to see the interview with the M.D.:

Via Jezebel.

Simon O., who sent in this ad for high-speed internet, tells us that the text reads “just suck it down.” He also tells us that the Austrian government pulled the plug (so to speak) on this advertisement.

But seriously… there is good evidence that pornography has driven a great deal of the innovation in communication techology since… well, since communication technology existed. Here’s a Guardian article on how it’s doing so even now.