The Scion is an interesting study in marketing. Scion (noun: descendant) is a subsidiary of Toyota. Why Scion? Well, Toyota wanted to sell cars to young, hip, urban guys but (as we all know) Toyotas are for fuddy duddies (yeah I’m talkin’ to you). So Toyota started Scion. Scions are really just Toyotas, less the fuddy duddy baggage. Toyota has marketed Scions accordingly. Here are some commercials:

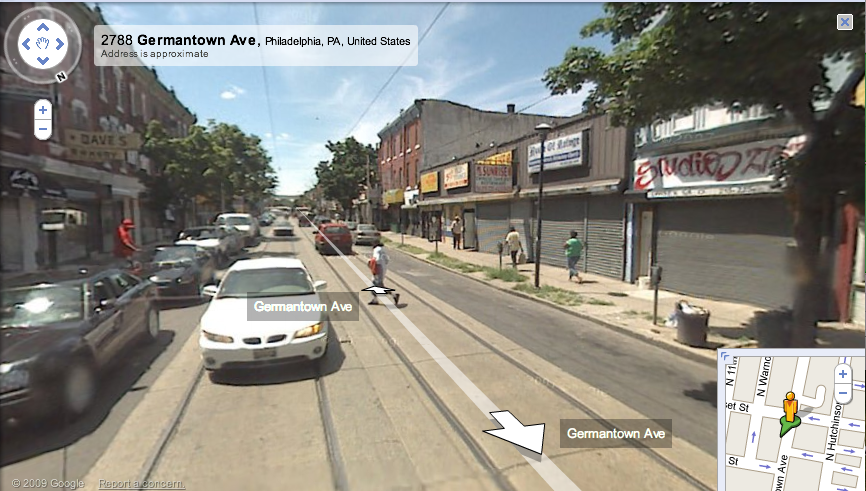

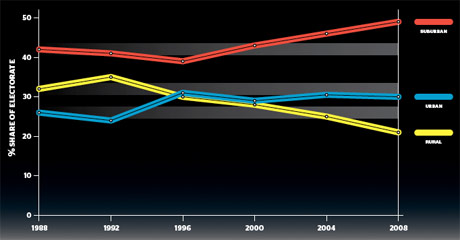

Scion advertising features young people of color, usually men, in urban spaces (found here):

I have a Scion. This one:

When I walked into the Madison, Wisconsin Toyota dealer to purchase it, there were a dozen middle-aged white men with pot-bellies, and a Latina that looked about 16 years old. She was the Scion salesperson. (Hi Celia!)

Also appealing to its intended customers, Toyota encourages you to customize your Scion. When I purchased the car, I had the option of adding neon trim around the bottom of the car, glowing cup holders, and giant speakers that took up the entire back seat. Factory installed. (I opted for all three, of course.)

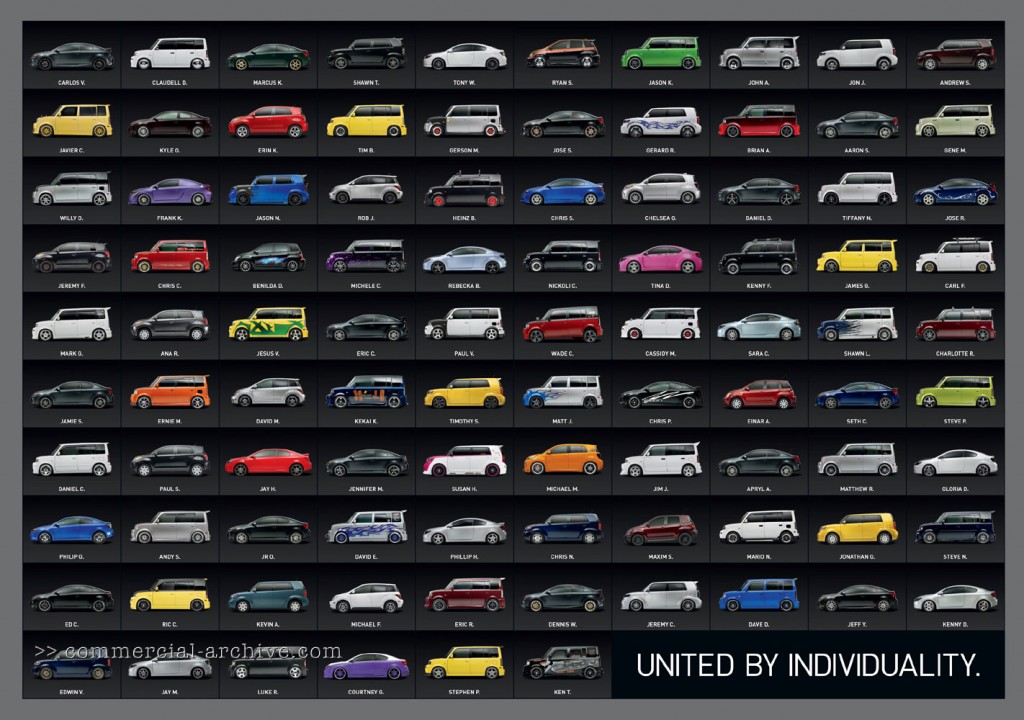

Scion encourages these additions. As the commercials show, Scion emphasizes customization and the individualization of your car. “United by Individuality” is one of their advertising themes (found here):

Underneath each of these unique Scions is the name of its owner. These names include Carlos V., Claudell D., Javier C., Benilda D., Jesus V., Kekai K., Nickoli C., Mario N., Einar A., Jose S., and Jose R. They’re definitely not marketing to the stereotypical Toyota crowd.

The marketing of the Scion points to how we separate old from young and then layer the binary with further binaries: boring/exciting, suburban/urban, conformity/individuality, and even white/non-white. Toyota doesn’t sell Scions by constantly reminding us that Scions are Toyotas (with all the dependability and efficiency that Toyotas are known for), just the opposite. And youth, Toyota appears to believe, want to differentiate themselves from dull, grown-up, suburban, whitebread conformity as much as possible.

But here’s the twist:

Celia (who I bought my Scion from in Madison, Wisconsin) told me that, despite all of their efforts, the “boxy” Scion (the one on the left in the first print ad) is bought disproportionately by elderly people. Why? Because the spacious interior holds a wheelchair just as easily as a mountain bike or a drum kit and the height of the car makes it easy to get in and out of without having to pull yourself up or lower yourself down.

Marketing, thanks to human creativity and free will, has its limits and marketers can’t always predict how their strategies will play.