Yesterday, one of my favorite blogs, Sociological Images, picked apart amputee alt model Viktoria’s appearance in Bizarre Magazine.

What makes Viktoria “bizarre”? Is it her amputated leg? Is it the fact that she has an amputated leg and is still incredibly sexy? Or is it that she has an amputated leg and still considers herself a sexual person? Is this empowering? And to who? Surely the disabled are desexualized in this country, so it’s nice to see that challenged even, I suppose, in a magazine about weirdos. And yet, I suspect her sexuality is acceptable, fetishizable, only because she conforms to expectations of feminine beauty. In the big scheme of things, does she reproduce the standard of beauty, unattainable for most women, that crushes women’s self-esteem and sense of self-worth? And will disabled women, most of whom (like most non-disabled women) could never dream of being so beautiful, actually look at her and be able to identify? Or will this just draw attention to another way in which they don’t match up?

Now really, I think that SocImages went a little overboard with Viktoria (especially when they dismissed her comments about sexuality as “standard porn star talk”). Maybe it’s because I know her little better than they do, but I think that they oversimplify the genuine place that she comes from in choosing to be a model. However, they do bring up an important discussion that’s been nagging me for some time. What is an alternative model, and what is an alt model’s role in visual culture? In my life, at various points, I came up with 3 different definitions. I believe in each of them, and I have a problem with each of them as well. Here they are below. Which one resonates with you? Do you think it’s a combination of the three below, or something completely different? Opinions, please.

1. The model who challenges society’s notions of beauty.

Examples:

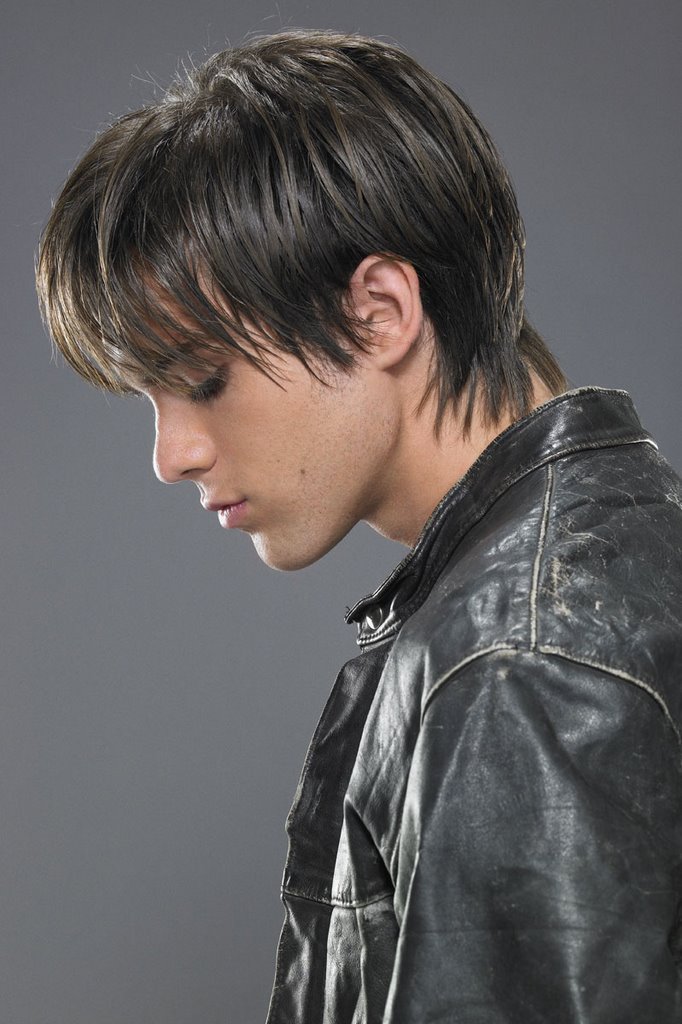

Kenyan-born trans model Biko Beauttah, photographed by Bode Helm.

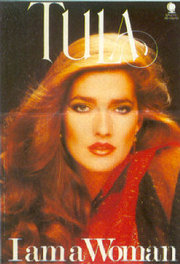

Velvet D’Amour, photography credit unavailable.

I love these models, but the issue here is that, while they appear to push the boundaries of beauty in some direction, they usually wind up brutally reinforcing another traditional notion in the process. For example, trans models make us rethink gender/beauty, but with their self-presentation they usually reinforce the ideal of a sleek, hairless feminine figure, thus fueling the hair-removal industry. In fact, epilator-manufacturer Philips Norelco has already found a way to to capitalize on this to great effect – just watch this ad. And large models like Velvet D’Amour and skinny-by-comparison but still-considered-plus-size recent ANTM winner Whitney Thompson help to redefine weight in modeling, but what makes them “legitimately beautiful” in the eyes of the mainstream world is their “correct” bone structure, their blond hair. Without some “redeeming quality” of this sort, the world doesn’t recognize them as models, and wouldn’t even give them a shot at making a difference. Mainstream media often presents them as beautiful “in spite of,” not “because of.” While their individual messages are empowering (I love Velvet’s interviews), I don’t find our culture’s use of these models empowering at all.

2. The hottie with strange hair/tattoos/piercings/latex.

Examples:

Mosh, photographed by Vance.

Scar13, photograhed by Nadya Lev.

Like it or not, it’s a valid definition – arguably the most widely-embraced one at that. This idea is epitomized by the Suicide Girls motto: “redefining beauty, one hot, naked chick at a time.” Underneath all the hair dye and black eyeliner, the ideal remains the same: symmetrical faces, clear skin and slim figures with a slightly above-average degree of variation as compared to mainstream modeling. Alterna-porn sites and alt modeling agencies such as Nocturnal Models helped cement this concept, but the biggest reinforcement came from self-proclaimed “alt photographers” and “alt models,” in whom they chose to include and exclude as they built up their online “spheres of influence.” This definition doesn’t make me happy now, though I had no problem with it at 21, when all I did was go clubbing and take pictures that reminded me of how I felt when I was dressed-up on the dance floor. When I realized that my own photography was reinforcing the same standards of beauty that make it difficult for women to have a healthy self-image, I took a step back.

3. The self-made persona.

Examples:

Feisty Diva wearing a hairpiece she created, photographed by Nadya Lev.

Anachronaut, photographed by Nadya Lev.

Another definition of alt model is someone who completely reinvents themselves from head to toe. This could be someone you’d never otherwise notice on the street, yet through inventive styling, self-applied makeup, self-styled clothing and hair, they create a whole new persona for themselves. The ultimate example of this is Mana, who goes from being a middle-aged man to a gothic Loli. These people make up their own beauty, owning their look from head to toe for the purpose of expressing an artistic ideal, proving a political point, etc. But are are they really “models,” or artists who allow you to take their portrait? It’s the most positive concept to me, but is it a valid definition of “model”?

So there you have it. Three definitions, some of which conflict with each other. And still, even after writing all of this out, I’m not sure if I’m even satisfied with my own personal definition, which draws on all three. Something’s bothering me. Something’s missing. Anyone have any idea?

—————————-

Nadya Lev, a photographer, blogs for the Coilhouse.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.