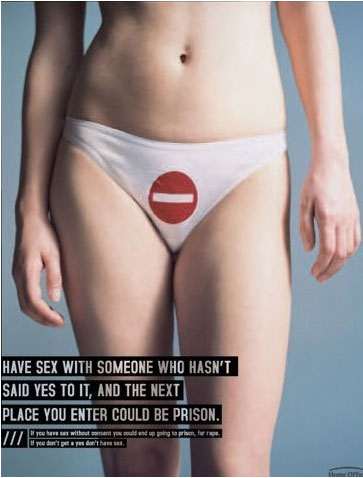

Re-posted to add to the discussion about sexual assault in the aftermath of the Steubenville rape trial, the Senate hearing on rape and harassment in the military, and the controversy at Occidental College.

On the heels of our recent post about an anti-rape ad that did the unusual — target men and tell then not to rape — comes this Scottish ad, sent along by Sociologist Michael Kimmel, that does a fantastic job of mocking the idea that some women are “asking for it”:

On the heels of our recent post about an anti-rape ad that did the unusual — target men and tell then not to rape — comes this Scottish ad, sent along by Sociologist Michael Kimmel, that does a fantastic job of mocking the idea that some women are “asking for it”:

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.