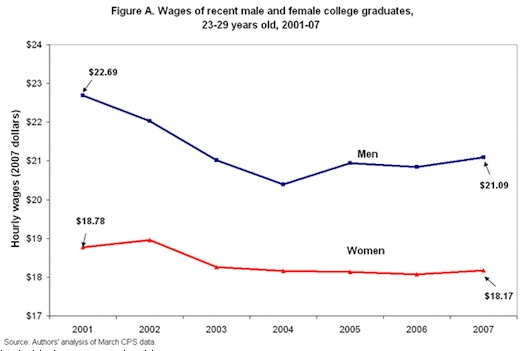

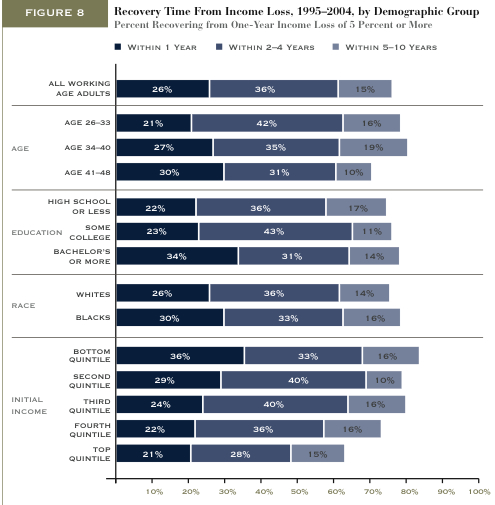

Matthew Yglesias featured two figures from the Pew Economic Mobility project. They show how long different types of people tend to take to recover from income loss (within 1 year, 2-4 years, or 5-10 years).

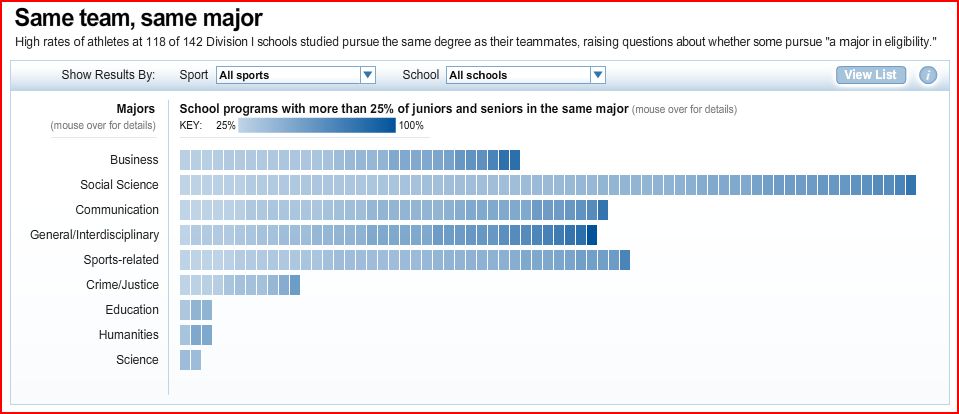

This figure shows that people who are older, have more education, or are poor, working, or middle class have a harder time recovering from tough economic times:

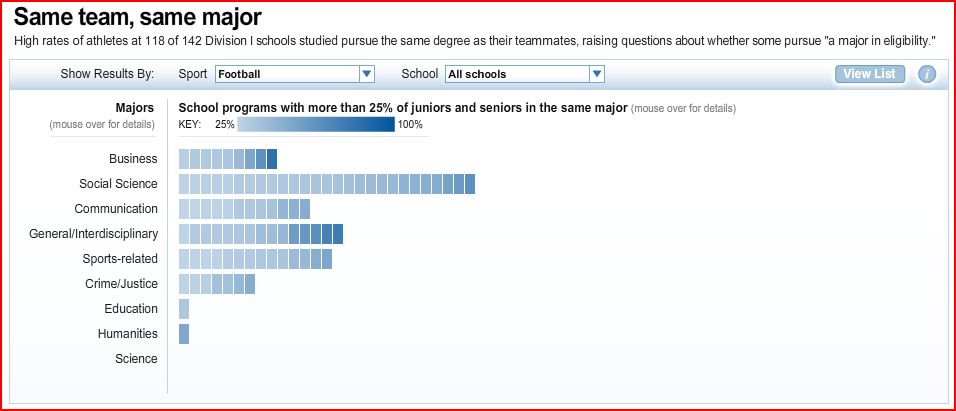

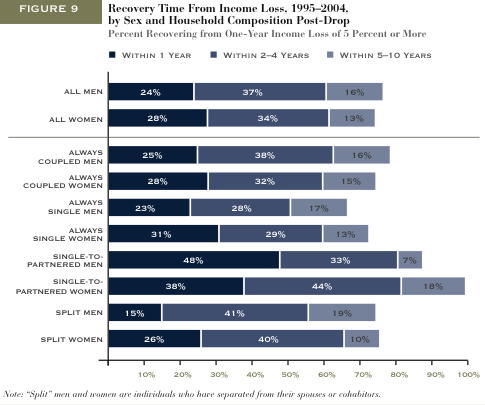

This figure shows how marital status is related to recovery. Most dramatically, people who get married before recovering financially (especially men), women who split with a partner, and women who are single have a more difficult time recovering.

Something to consider: As several commenters noted, I’m not sure how they defined “recovery” from income loss. If you never made a lot of money to begin with, does recovery simply mean returning to a state of low income? Then, does the income for an initially high income person need to return to its high state for it be counted as a “recovery”?

(Just FYI: I revised my interpretation of these figures. Thanks to the early commenters who noticed I’d misinterpreted. It was really late at night when I wrote this post!)

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.