In City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles, Mike Davis discusses the ways that public space are increasingly regulated to allow the types of activities preferred by the middle class and exclude those of the urban poor. He says that cities operate under “a rhetoric of social welfare that calculates the interests of the urban poor and the middle classes as a zero-sum game” (p. 224). That is, there are various uses groups might have for public space, but over time, activities or behaviors associated with the poor are being pushed out of public places (say, trying to make money or taking a nap), because they are seen as inherently interfering with more middle-class uses. While outlawing certain behavior in public places is often explained as a way to ensure safety, Davis argues, “…’security’ has less to do with personal safety than with the degree of personal insulation, in residential, work, consumption and travel environments, from ‘unsavory’ groups and individuals…” (p. 224).

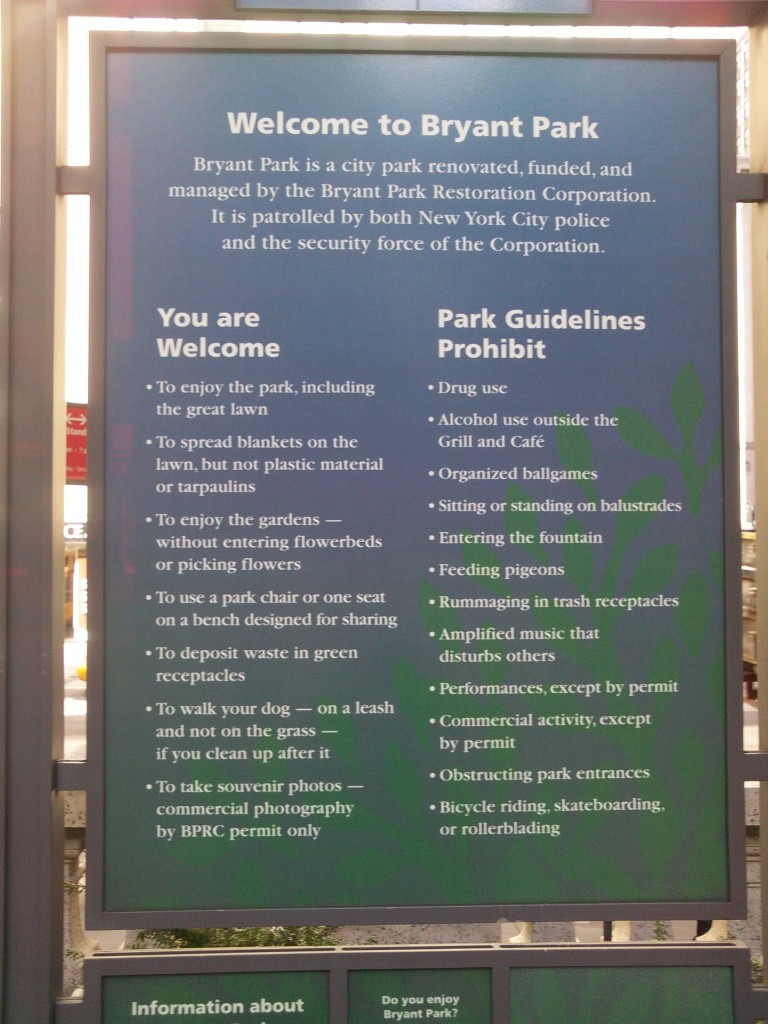

I thought of Davis’s argument when I saw this photo send in by Dino of a sign in Bryant Park, in Manhattan. The sign welcomes visitors to enjoy the park, but under clear conditions:

It’s a good example of the zero-sum idea of use of public space: the acceptable ways of using the park are those that generally meet middle-class preferences, such as taking amateur photos, looking at flowers, walking your dog. But as Dino says, “the poor are punished: alcohol use in the park is illegal unless you can afford to enter the restaurants, rummaging through the garbage for needed food and supplies is illegal, trying to earn money without a permit (that costs money) is illegal.”

Note the second item you are “welcome” to do: “To spread blankets on the lawn, but not plastic material or tarpaulins.” While the sign doesn’t explicitly say why, Dino suspects this is an attempt to allow people to spread blankets for picnics or sunbathing, but not allow someone without a home to spread a tarpaulin to try to create a dry place to sleep. Similar behavior — spreading a covering on the ground to sit or lie on — is perceived differently depending on the presumed motivation for doing so (because you are temporarily enjoying the outdoors vs. because you don’t have a home).

The end result is to make public places less welcoming to some groups than others. Regulating these behaviors provides an excuse to arrest and remove the types of individuals likely to be seen as, in Davis’s term, “unsavory,” and ensures the rights of other users to be protected from even seeing evidence of homelessness, hunger, or unemployment.

UPDATE: I don’t think I did the best job of explaining Davis’s argument, and a couple of readers have taken great exception to the idea that regulating behavior in public spaces is problematic. My intention wasn’t to imply that having any type of rules about how you can act in parks is automatically awful, but rather to highlight the types of behaviors we do find acceptable and those we don’t, and how that intersects with the stigmatization of poverty. Saying “You can’t harass others in the park” or “you can’t play music so loudly that others can’t also enjoy the park” is one approach. Saying, “We’re going to make public spaces unpleasant for the homeless, regardless of their individual behavior,” is a very different approach, and Davis argues that it serves to concentrate the very poor in areas like L.A.’s Skid Row, increasing their likelihood of being victimized and exacerbating the problems of the neighborhood, while benefiting those in other neighborhoods who don’t want to see visible evidence of inequality or social problems.

Reader R says,

I think this is a really interesting discussion but I think that the Park sign doesn’t help the discussion but hinders it. We are now focusing on this sign as a representation of the ideas that Davis is presenting but I don’t think that it is.It is illegal to have any alcohol in a public space anywhere in new york city.New York City Administrative Code, section 10-125 That law I don’t believe is intended as a means to keep the homeless from drinking in parks, it does let the police enforce that but it also lets the police stop and arrest college students or any person. Fair or not that is what it is.

Also Bryant Park is a public space owned by a private company. The BPC (Bryant Park Corporation) does not get public funding but instead makes it through the venders in the park (cafes and such). This is why I believe that the sign says no commercial activity. With that I do not think many people would count someone asking for change as commercial activity.I think this is a very interesting discussion and Davis makes very valid points but I think the imagery example could be better.

I think that’s a fair assessment. The sign got me thinking about Davis’s arguments about the use of social policy regarding public places (and the way they can concentrate poverty, risk, etc.), and then I was thinking more about the overall topic, rather than the specific park or sign.

Comments 86

N — November 13, 2010

Is it Davis's argument that all publicly funded spaces aught to be available to the homeless for shelter or that these rules discriminate against people from other economic classes between homelessness and upper middle class? The city provides many services to the homeless, why is it necessary that Bryant Park be available to the homeless as additional shelter?

As for the rule against commercial activity, why should this place be available for commercial vendors free of charge? In order to set up any commercial enterprise one is usually expected to pay, and since the city provides the vendors who do pay with services (cleaning, gardening and customers) why is it unreasonable that they should have to pay for permits.

I see how the rules against amplified music and ballgames imply that certain people are not welcome, I don't see why the rules against picking through garbage or selling without a permit are unreasonable. To be clear, I am asking these questions in earnest.

Kelly — November 13, 2010

Ha. See: going anywhere with children, esp. small ones.

Sue — November 13, 2010

As a middle-aged black woman who grew up in a poor area of New York City, and remembers when Bryant Park was a dangerous, addict-filled, uncrossable stretch called "Needle Park," I find this post utterly ridiculous.

How about the right of poor people to enjoy "middle class" comforts like a pleasant environment? We're not all down with headache-inducing hip hop. Sometimes we just want to take a little break.

Millions of dollars were poured into Bryant Park to restore it to its 19th Century glory. It's a jewel, only a block or two in each direction, and it hosts many public events, including an outdoor movie program in the summer, juggling classes, and a skating rink, which I think is free some part of the day.

There are rules because we don't share a common understanding of how public property should be enjoyed and used. And clearly you haven't been in Central Park or Riverside Drive Park. You'll find masses of people engaging in all the forbidden behavior listed on the Bryant Park sign.

You also don't seem to have considered the practical consequences of some of the rules, for example, people who bring blankets are more likely to take them home; people who use tarps often leave them strewn all over the place. Plastic also is probably more damaging to the environment than blankets. Bryant Park is a heavily landscaped area.

SI -- You really need to get out more before parroting naive drivel. Sociologists who hold poor people to lower standards are condescending, and, to use a Sixties expression, part of the problem.

This post is infuriating in its idiocy.

Sue — November 13, 2010

By the 1970s, Bryant Park had been taken over by drug dealers, prostitutes and the homeless. It was nicknamed "Needle Park" by some, due to its brisk heroin trade, and was considered a "no-go zone" by ordinary citizens and visitors.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bryant_Park

http://www.bryantpark.org/

Sue — November 13, 2010

"And clearly you haven’t been in Central Park or Riverside Drive Park. You’ll find masses of people engaging in all the forbidden behavior listed on the Bryant Park sign.'

--"All the forbidden behavior," and much, much more. Want to hear about the time when I was 18 and came across the guy jacking off in the Shakespeare Garden in Central Park? In the middle of the day.

Sue — November 13, 2010

The focus of the post is on that sign, the behavior it forbids, and its alleged disparate impact on poor people.

"His argument (which I didn’t make clear, I realize) is that we used to have public policies that somewhat balanced regulation and services, but increasingly only focus on regulation:"

I suggest you look at the history of the loitering and vagrancy laws in the U.S. Homeless people were routinely locked up simply for not having a job and being a non-resident. There were few, if any services.

"...we want the homeless out of our parks, we don’t want to have to see someone asleep on a bench, and there’s little concern about where they will go instead."

The problem of caring for the homeless is a continuing one. But in New York one sees homeless people everywhere, on the street, in the subway, and in the park. Generally, they aren't bothered; if anything, it's the other way around. I've never heard of any anti-homeless person government brigade except on the coldest nights in the winter when the police attempt to take homeless people to shelters. I understand why some of them don't want to go. The shelters are very dangerous. You can get robbed or raped there.

But even if the rules explicitly forbade homeless people, I don't see that there's a "right" to live in a park, especially a very small park.

Oh, I checked and the Bryant Park skating rink, which is open now, is free. If you look at the site, it's a beautiful park. It's a multi-use park, but you can get a lot of enjoyment from it even if you're not wealthy.

T — November 13, 2010

There are several items on that list that I would enjoy doing in the park, but are forbidden. Yes, it is about "city norms of public space use." It is restrictive to *maximize* the enjoyment of the public space.

A homeless person camping in the park is not against the rules because "Eeeuw, a homeless person" -- it's because it's a misuse of the public property and limits the maximization of enjoyment by all.

The homeless are not removed from the park -- but rather, what the homeless do in the park is restricted. In the same way everyone else's activities are restricted.

And this: "what happens when we want the removal of evidence of social problems, without concurrently addressing them?" I take your point, but are you telling me that the homeless man sleeping on a park bench is a social performance?!

R — November 13, 2010

I think this is a really interesting discussion but I think that the Park sign doesn't help the discussion but hinders it. We are now focusing on this sign as a representation of the ideas that Davis is presenting but I don't think that it is.

It is illegal to have any alcohol in a public space anywhere in new york city.

New York City Administrative Code, section 10-125

That law I don't believe is intended as a means to keep the homeless from drinking in parks, it does let the police enforce that but it also lets the police stop and arrest college students or any person. Fair or not that is what it is.

Also Bryant Park is a public space owned by a private company. The BPC (Bryant Park Corporation) does not get public funding but instead makes it through the venders in the park (cafes and such). This is why I believe that the sign says no commercial activity. With that I do not think many people would count someone asking for change as commercial activity.

I think this is a very interesting discussion and Davis makes very valid points but I think the imagery example could be better.

Lacin T. — November 13, 2010

It's been an interesting post (as a whole) to show how we make peace (!) with middle class norms...

I didn't think the idea here was directly about shelter for the poor or hail to the drug addicts... It seems about regulation and how we normalize that it's a no-no to "feed pigeons" under a discussion like "well, it was a bad bad place before, drug and sex and too much rock'n roll" (maybe other genres?) Problems aren't going away, they just change places, for one thing. For another, people compare past and present by what remains of the fears from a past that they clearly know well

At least Davis was right in using "fear" as a central theme in his works.

By the way, this post made me think of a recent news on a small town in Italy. Around the place, they included, among many other interesting regulations, "feeding stray cats" is a no-no for the sake of making the town a good place for tourist-public. Here's the link to the news-piece: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-11617091

Gwen Sharp, PhD — November 13, 2010

I don't know why I find that restriction particularly surprising, just for some reason I do. Now I'm thinking of any time I've, as an adult, gone to a playground alone or with friends to sit at a table and read or swing or whatever. It's weird to suddenly realize that I was, by current standards, apparently being a perv.

Sue — November 13, 2010

Some thought was given to making Bryant Park inviting to the public. They consulted with a sociologist:

"[A sponsor of Bryant Park] worked with William H. Whyte, the American sociologist and distinguished observer of public space. Whyte’s influence led Biederman to implement two decisions essential to making the park the successful public space that it is.

"First, Biederman insisted on placing movable chairs in the park. Whyte had long believed that movable chairs give people a sense of empowerment, allowing them to sit wherever and in whatever orientation they desire.

"The second decision was to lower the park itself. Until 1988, Bryant Park had been elevated from the street and further isolated by tall hedges, a design conducive to illegal activity. The 1988 renovation lowered the park to nearly street level and tore out the hedges.

After a four-year effort, the park reopened in 1992 to widespread acclaim. Deemed "a triumph for many" by NY Times architectural critic Paul Goldberger, ... the renovation was lauded not only for its architectural excellence, but also for adhering to Whyte's vision.

"'He understood that the problem of Bryant Park was its perception as an enclosure cut off from the city; he knew that, paradoxically, people feel safer when not cut off from the city, and that they feel safer in the kind of public space they think they have some control over.'"

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bryant_Park

I didn't know any of this. Interesting.

meave — November 13, 2010

As a San Francisco resident, the prohibition that stuck out to me is the one against "rummaging in trash receptacles." In parks here, there are always people with their shopping carts full of recyclables. Sometimes they approach you if you've got empty bottles/cans around, but usually they're "rummaging in trash receptacles" for recyclables to add to their carts. I don't know how it works in New York, but we could never make a rule like that here, it'd be cruel. Why would anyone begrudge a person--most likely a homeless person--the opportunity to make a few dollars from collecting the recycling? And if it's a case of "rummaging in" actual trash looking for food scraps--to me, that seems very degrading, but I would never stop someone from doing that. What is the harm?

Maybe NYC has had trash problems? Or your waste management company doesn't like scavengers? We do not treat our homeless population very well, but we don't deny them access to park trash, so I'm really curious about that particular rule.

Meg — November 13, 2010

"...activities or behaviors associated with the poor..."

Associated by who?

I think it's wrong to automatically assume the behaviors on the right somehow apply more to "poor" people and that the behaviors on the left apply more to "middle class" people. And, also, while we could discuss the meaning of "poor" without end, there's a lot of people between homeless and middle class -- or even poor and middle class.

Even "poor" people enjoy nice quiet parks. Assuming that outlawing rowdy behaviors is targeting the poor says more about the author's stereotypes of poor people. It seems that most of the rules have to do with keeping the park clean and reducing liability (like if someone slipped and drowned in the fountain, hurt themselves while roller-blading, or got mobbed by over-eager, pooing birds). Yes, it may be a bit nanny-state of them, but it's hardly anti-poor people. And even the thing about plastic tarps could be because blankets are less likely to damage the grass because blankets breathe better and are less likely to be left on the spot overnight. Plus, they're less likely to leave brittle plastic bits behind.

Sue — November 13, 2010

It's hard to criticize a park as insensitive to people without employment when it provides a free reading room (now closed for the year):

"Reading Room

The original Reading Room began in August of 1935 as a public response to the Depression Era job losses in New York. Many people did not have anywhere to go during the day, and no prospects for jobs. The New York Public Library opened the “Open Air Library” to give these out-of-work businessmen and intellectuals a place to go where they did not need money, a valid address, a library card, or any identification to enjoy the reading materials.

The 1935 Reading Room consisted of several benches, a few book and magazine cases, and a table with a beach umbrella for the five librarians who ran it. It operated every day except Sunday from mid-morning until mid-evening. Most of the books were from the New York Public Library’s circulation, but all magazines and trade publications were donated by publishers or individuals. When it rained the books and periodicals were quickly put in a large water-proof chest and readers and librarians took cover. No cards were required – patrons were simply asked to sign in and out. The Reading Room was closed in 1944 due to an increase in jobs and World War II.

****The Bryant Park Corporation has repeated history by recreating the Bryant Park Reading Room. It is modeled after the original with the additions of custom-designed carts for an extensive and eclectic selection of books, periodicals and newspapers; readings and programs at lunchtime, after work and for kids; movable furniture to create a more intimate environment; and kid-sized carts and furniture for children to use. The programming, publications, and environment of the Reading Room are available to everyone for free, without any need of cards or identification."

http://www.bryantpark.org/things-to-do/reading_room.html

Paul — November 13, 2010

Seattle has a lot of these rules. It's illegal to sit or lie down on the sidewalk, and most of the public benches are designed in such a way as to make it impossible to lie down on them. The city also tried to make a rule against smoking in city parks, and a law against "aggressive panhandling," which was broadly defined. The latter two were shot down.

The smoking thing is a great illustration. I can't *stand* the smell of cigarettes, plus second-hand smoke is just as carcinogenic. So in a way I'd be happy to have all smokers banned from public places. But homeless people smoke, I'm told, because it keeps down the hunger pangs. They smoke because they've got nothing to eat. On that basis, a smoking ban would be not just an inconvenience, but actual cruelty.

Thing is, behaviors like garbage-rummaging and camping in parks are often obnoxious to others and have real health-and-safety concerns. So these rules have tangible benefits--but only to some. To those who are probably just as revolted by park-camping but don't have any other options, the rules have no benefits. And "who's benefiting from this?" is always a great question to ask...

Sue — November 13, 2010

I'm being sarcastic, but I'm seriously wondering if this is how the Sociology field works:

Argue that rational norms for disadvantaged, marginal groups should be relaxed; make a career "sympathetically" analyzing the horrendous fallout.

I'm sure that sociologists have compressed this idea into a clever epigram. You should do a post on it.

AR+ — November 13, 2010

None of the things alleged to be "middle class" here can't be enjoyed by the poor, to. There are multiple orders of magnitude between "middle class" and "destitute," and not being middle class doesn't automatically mean being homeless, rummaging thru trash, and doing drugs in public parks.

It is in fact the working poor who benefit most of all from this sort of thing, because the middle class and wealthy can afford to operate their own safe and pleasant spaces if they have to, but they aren't the only ones who want to enjoy a quite park.

mo — November 14, 2010

I'm going to have to agree with Reader R on how they read the sign. I'm very careful about what is public property and what is private property open to public use, precisely because I know my rights as a photographer. The way that sign is worded (including the lack of capitalization on "city park") means that the corporation owns that space in the city and has opened it to public use with rules. Private property owners are allowed to set rules of conduct for their property. The big tip-off was the prohibition of commercial photography without consent, which is allowed on private property. (and the private security patrols)

I do agree that the "rules" here are very obviously designed to keep certain stratas of society from using the space. It's just that they've figured out how to do it by retaining ownership of the property.

decius — November 14, 2010

Wait... who saw "Drug use" and "Alchohol use [outside resturants]" as being behavior associated with the homeless? Of the four alcholoics that I have known of in my life, only one was homeless; according to him, he was a funtioning alcoholic for years before economic conditions put many people (including myself) homeless. Of the seventy or so homeless people that I know, only two had visible drug issues.

Notable among the habits of the homeless that I observed was that they would create camps, using (gasp!) plastic tarps. The camps were often located out of public sight, near the shelter, to reduce police harrassment. Living in the shelter would subject them to harrassment by the shelter staff. Had they anything of value, it would be easily stolen.

Disturbingly, most homeless I have known fell into the same category: People who were living paycheck to paycheck and lost their job. Some did not qualify for unemployment, many more (mistakenly) thought that they didn't qualify, and some (like me) either exhausted it or found it inadequate to pay for housing. Few, but not none, had severe psychological issues that made living a working-class lifestyle impossible.

Frankly, a park with little illegal activity, with vendors who may or may not be sympathetic with donations of food that fall between "fit for human consumption" and "suitable for sale" is very attractive to the homeless like me. I presume that there's a rule, unstated, prohibiting camping. That means that homeless need somewhere else to sleep.

thewhatifgirl — November 15, 2010

I have to take issue with the addition you posted by Reader R (unfortunately, I don't have time to read all of the comments or find hers/his right now). In Sweden, people are allowed to drink in public. Sweden does not have a big homeless problem. They also have extensive park areas with absolutely no signs at all, and I don't think I ever saw a garbage can in any of their park areas either. Yes, their culture is different (see, for instance, Allesmansrätt) but I can't help thinking that it is not just a cultural difference.

digital — November 15, 2010

spy products, self defense products, gsm baton, spy pepper spray, spy gsm phonestun gun, Stun Baton baton, gsm bug for www.one-stop-digital.com

jo — November 15, 2010

Note the second item you are “welcome” to do: “To spread blankets on the lawn, but not plastic material or tarpaulins.” While the sign doesn’t explicitly say why, Dino suspects this is an attempt to allow people to spread blankets for picnics or sunbathing, but not allow someone without a home to spread a tarpaulin to try to create a dry place to sleep. Similar behavior — spreading a covering on the ground to sit or lie on — is perceived differently depending on the presumed motivation for doing so (because you are temporarily enjoying the outdoors vs. because you don’t have a home).

...this is really much ado about nothing. They don't allow plastic tarps in parks because it quickly kills the grass underneath. They usually ask people to not use plastic at any large outdoor concerts in the NYC parks.

Reader — December 3, 2010

Video and articles about the cleaning up of Times Square. Bryant Park is not that far away and had exactly the same kinds of problems. People who blather on about "unfair rules" need to educate themselves.

http://video.nytimes.com/video/2010/12/03/nyregion/1248068992455/cleaning-up-the-deuce.html?ref=nyregion

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/04/nyregion/04square.html?_r=1&hp

Psychology Question - Peakassignments.com — November 11, 2023

[…] Regulating Public Spaces – Sociological Images (thesocietypages.org) […]

Psychology Question - assignmentsproficient.com — November 14, 2023

[…] Regulating Public Spaces – Sociological Images (thesocietypages.org) […]