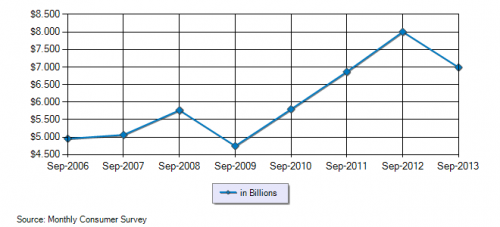

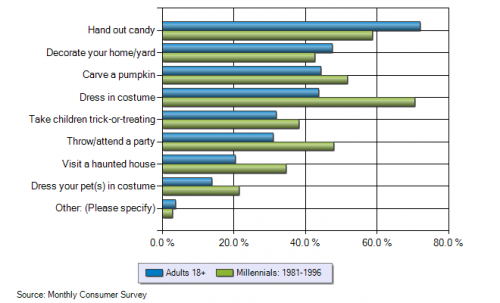

Yesterday I wrote about how the money spent on adult Halloween revelry now rivals, or even exceeds, that spent on kids. This may seem like a surprising shift, but it turns out it’s the focus on children that’s new. Halloween as the kid holiday we know it in the U.S. today was really invented in the 1950s.

This, and more fun facts about the history of Halloween, in this two-minute History Channel summary:

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.