Flashback Friday.

Add to the list of new books to read Delusions of Gender: How Our Minds, Society, and Neurosexism Create Difference, by Cordelia Fine. Feeding my interest in the issue of sexual dimorphism in humans — which we work so hard to teach to children — the book is described like this:

Drawing on the latest research in neuroscience and psychology, Cordelia Fine debunks the myth of hardwired differences between men’s and women’s brains, unraveling the evidence behind such claims as men’s brains aren’t wired for empathy and women’s brains aren’t made to fix cars.

Good reviews here and here report that Fine tackles an often-cited study of newborn infants’ sex difference in preferences for staring at things, by Jennifer Connellan and colleagues in 2000. They reported:

…we have demonstrated that at 1 day old, human neonates demonstrate sexual dimorphism in both social and mechanical perception. Male infants show a stronger interest in mechanical objects, while female infants show a stronger interest in the face.

And this led to the conclusion: “The results of this research clearly demonstrate that sex differences are in part biological in origin.” They reached this conclusion by alternately placing Connellan herself or a dangling mobile in front of tiny babies, and timing how long they stared. There is a very nice summary of problems with the study here, which seriously undermine its conclusion.

However, even if the methods were good, this is a powerful example of how a tendency toward difference between males and females is turned into a categorical opposition between the sexes — as in, the “real differences between boys and girls.”

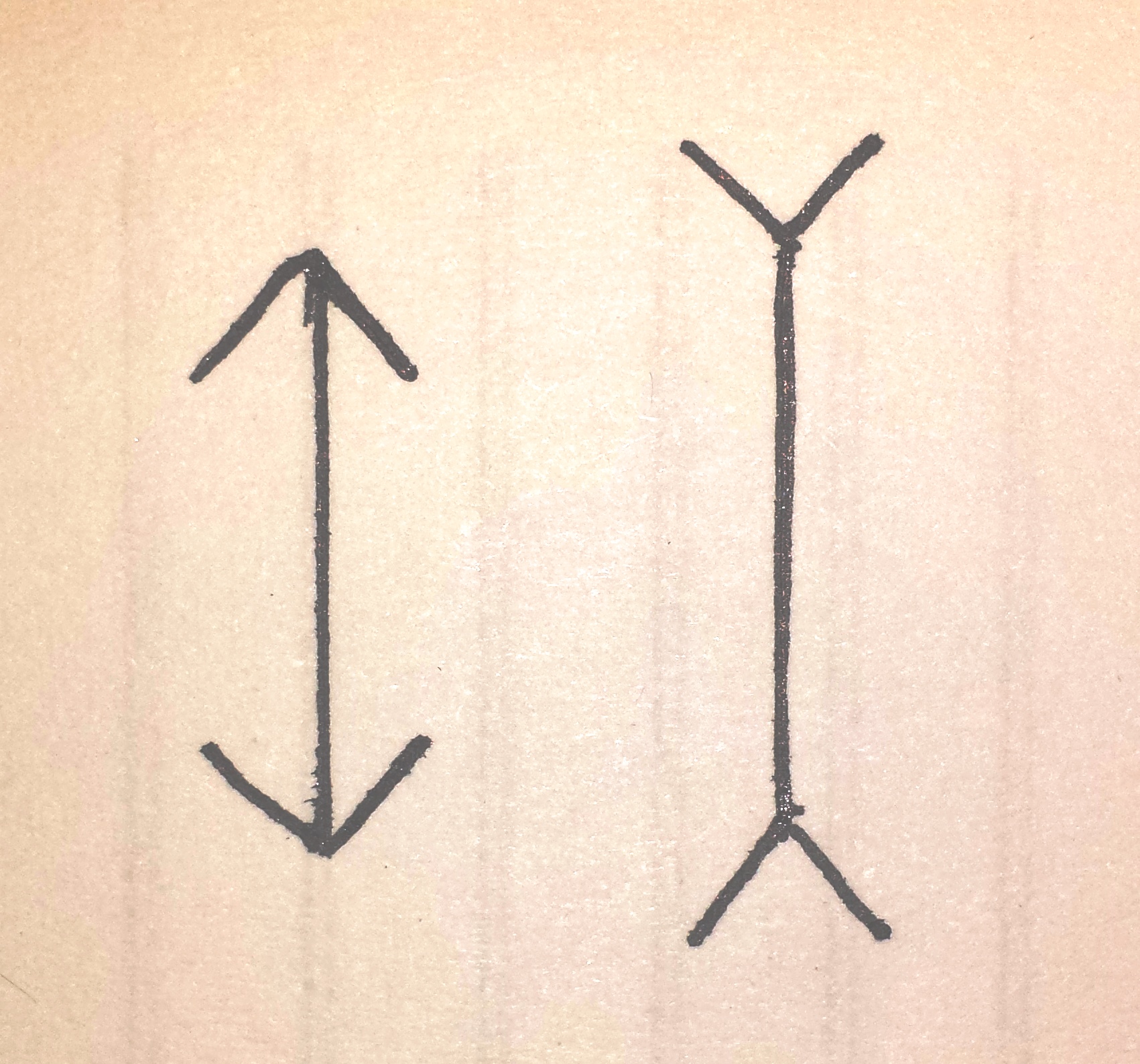

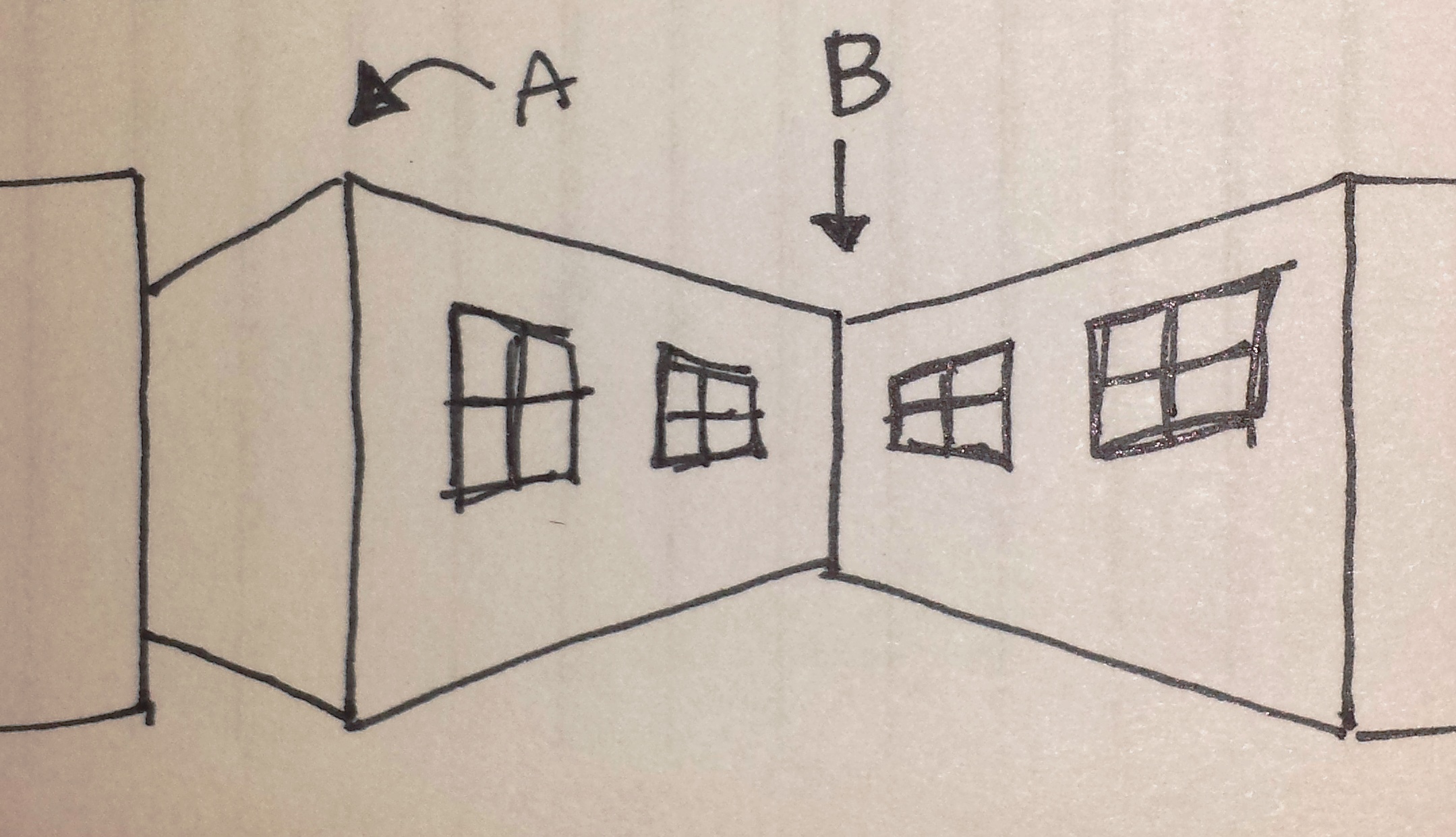

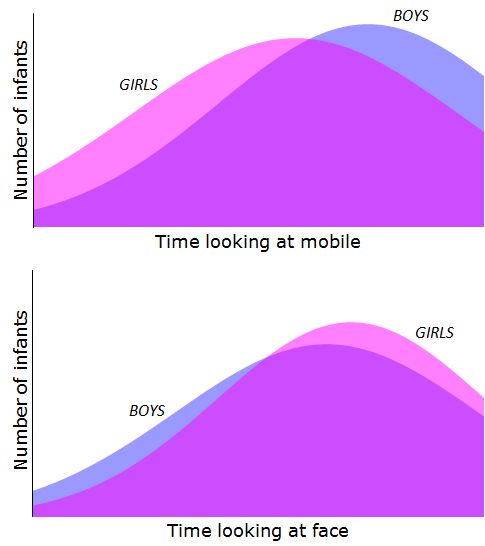

To illustrate this, here’s a graphic look at the results in the article, which were reported in this table:

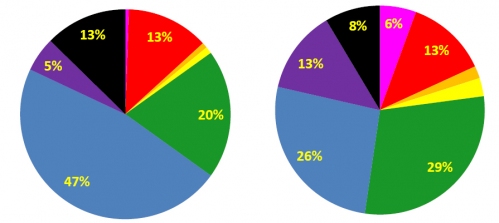

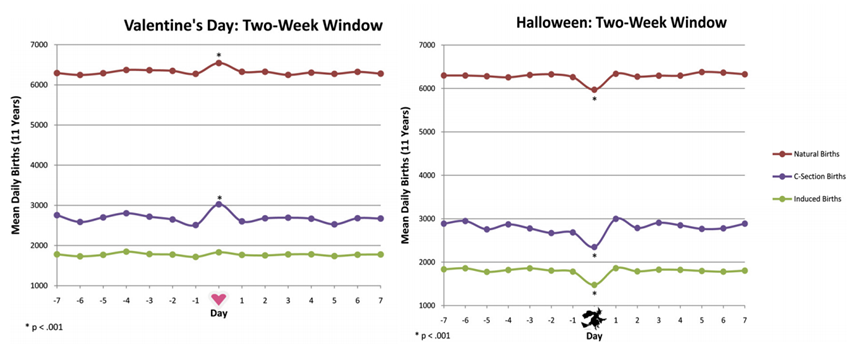

They didn’t report the whole distribution of boys’ and girls’ gaze-times, but it’s obvious that there is a huge overlap in the distributions, despite a difference in the means. In the mobile-gaze-time, for example, the difference in averages is 9.7 seconds, while the standard deviations are more than 20 seconds. If I turn to my handy normal curve spreadsheet template, and fit it with these numbers, you can see what the pattern might look like (I truncate these at 0 seconds and 70 seconds, as they did in the study):

They didn’t report the whole distribution of boys’ and girls’ gaze-times, but it’s obvious that there is a huge overlap in the distributions, despite a difference in the means. In the mobile-gaze-time, for example, the difference in averages is 9.7 seconds, while the standard deviations are more than 20 seconds. If I turn to my handy normal curve spreadsheet template, and fit it with these numbers, you can see what the pattern might look like (I truncate these at 0 seconds and 70 seconds, as they did in the study):

Source: My simulation assuming normal distributions from the data in the table above.

Source: My simulation assuming normal distributions from the data in the table above.

All I’m trying to say is that the sexes aren’t opposites, even if they have some differences that precede socialization.

If you could show me that the 1-day-olds who stare at the mobiles for 52 seconds are more likely to be engineers when they grow up than the ones who stare at them for 41 seconds (regardless of their gender) then I would be impressed. But absent that, if you just want to use such amorphous differences at birth to explain actual segregation among real adults, then I would not be impressed.

Originally posted in September, 2010.

Philip N. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park. He writes the blog Family Inequality and is the author of The Family: Diversity, Inequality, and Social Change. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.

Botox has forever transformed the primordial battleground against aging. Since the FDA approved it for cosmetic use in 2002, eleven million Americans have used it. Over 90 percent of them are women.

Botox has forever transformed the primordial battleground against aging. Since the FDA approved it for cosmetic use in 2002, eleven million Americans have used it. Over 90 percent of them are women.