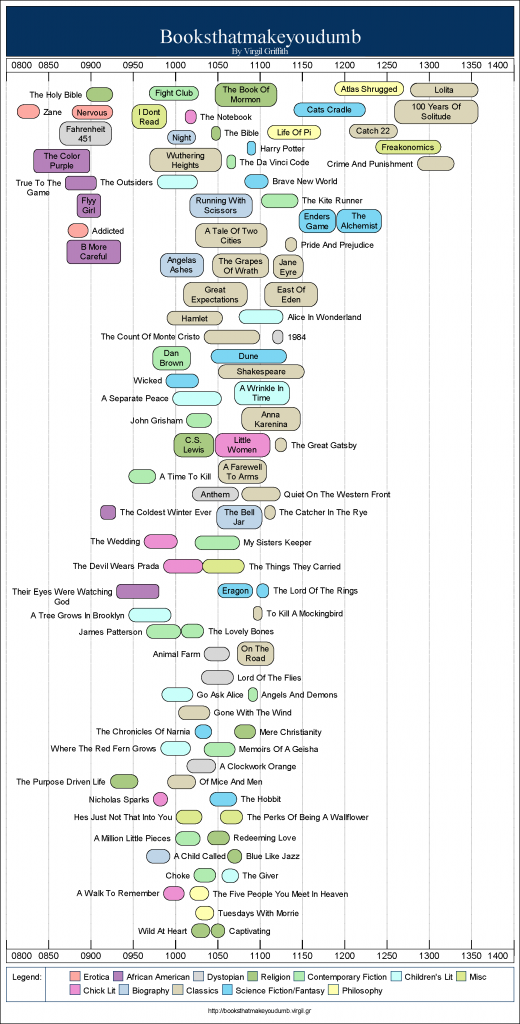

Jessica F. pointed out an interesting graphic at Fleshmap. They looked at which body parts are emphasized or referenced in different genres of music.

From the website:

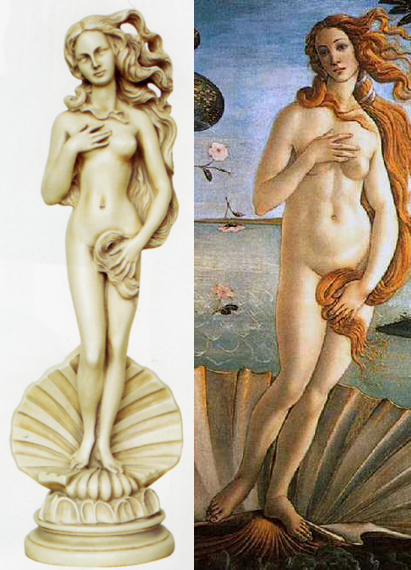

Fleshmap is an inquiry into human desire, its collective shape and individual expressions. In a series of studies, we explore the relationship between the body and its visual and verbal representation.

You can also click on the genre headings and go to a larger breakdown of what percent of songs reference each body part.

I find this fascinating, in that it gives us some indication of which body parts might be considered particularly important for defining attractiveness to artists and listeners of various genres…and also which body parts are most likely to be criticized or ridiculed. After all, a reference to a body part may be mocking as well as complimentary.

Of course, there are always issues with dividing artistic works into genres (Who defines the genres? How do you decide which genre songs go into if they have things in common with things in more than one genre?). And while the website provides a methodology, it could definitely be clearer:

Based on a compilation of more than 10,000 songs, the piece visualizes the use of words representing body parts in popular culture. Each musical genre exhibits its own characteristic set of words, with more frequently used terms showing up as bigger images. The entrance image shows how many times different body parts are mentioned; the charts for each genre go into more detail, showing the usage of different synonyms for each part.

They don’t specify how many songs were in each genre, how they were assigned to genres, or what the compilation of 10,000 songs is. I wish we had that info. Still, it does tell us, generally, about some interesting patterns that show how different groups construct–and appreciate–the body differently.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.