Cross-posted from Family Inequality.

The Supreme Court’s decision in the Dukes v. Wal-Mart case, Justice Scalia acknowledged that Wal-Mart’s many local managers had a lot of discretion in their personnel decisions, even though the company had a written policy against gender discrimination (who doesn’t?). But he gave the company credit for a vague policy and let it off the hook for a systematic pattern of disparity between men and women. So, when does a toothless, vague policy with wide discretion lead to a bad outcome, and is failing to prevent it the same as causing it?

A path-breaking sociological analysis of organizational affirmative action outcomes has shown that the companies that successfully diversify their management are most likely to have policies with teeth – where accountability is built into the diversity goal. In light of the Wal-Mart case, this led to a rollicking debate about how to think about “corporate culture” versus policies, and when to blame whom, legally or otherwise – which even divided sociologists.

Smoking in the movies

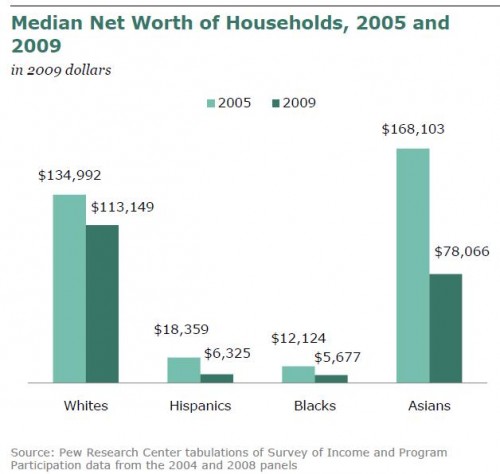

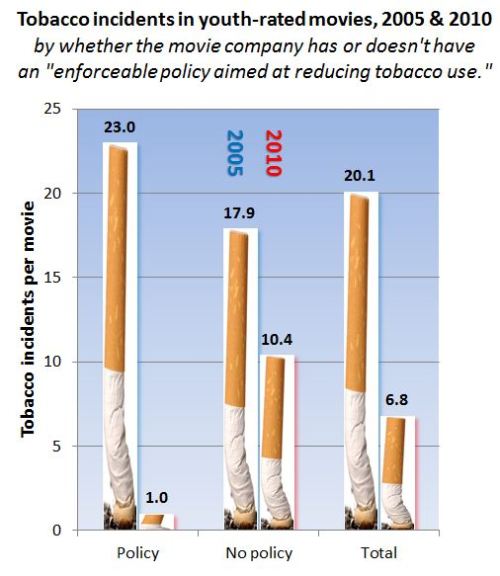

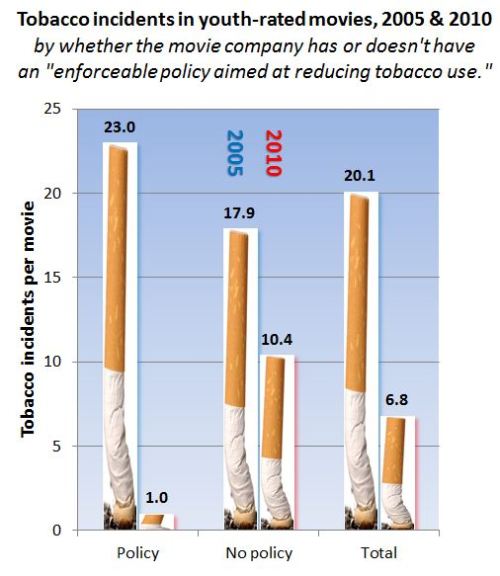

Here’s an interesting, at-least-vaguely related case. Positive depictions of smoking in the movies are widely understood to be harmful. Yet, smoking is also glamorous, artistic, and popular – representing both anti-adult rebellion and maturity. So, what to do? The Centers for Disease Control, in the always-riveting Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, has published a fascinating report on this topic. They report the number of tobacco incidents* in top-grossing, youth-rated (G, PG, PG-13) movies, and divide them between those that implemented an anti-tobacco policy and those that didn’t — helpfully cutting the movie industry roughly in half — and provide a simple before-and-after tabulation:

From 2005 to 2010, among the three major motion picture companies (half of the six members of the Motion Picture Association of America [MPAA]) with policies aimed at reducing tobacco use in their movies, the number of tobacco incidents per youth-rated movie decreased 95.8%, from an average of 23.1 incidents per movie to an average of 1.0 incident. For independent companies (which are not MPAA members) and the three MPAA members with no antitobacco policies, tobacco incidents decreased 41.7%, from an average of 17.9 incidents per youth-rated movie in 2005 to 10.4 in 2010, a 10-fold higher rate than the rate for the companies with policies. Among the three companies with antitobacco policies, 88.2% of their top-grossing movies had no tobacco incidents, compared with 57.4% of movies among companies without policies.

The difference is dramatic, as indicated by this image about the images. (Because I turned the columns into cigarettes, this is not just a graph, but an infographic):

The policies provide what may be an ideal mix of accountability and responsibility, short of a simplistic ban.

[The policies] provide for review of scripts, story boards, daily footage, rough cuts, and the final edited film by managers in each studio with the authority to implement the policies. However, although the three companies have eliminated depictions of tobacco use almost entirely from their G, PG, and PG-13 movies, as of June 2011 none of the three policies completely banned smoking or other tobacco imagery in the youth-rated films that they produced or distributed.

Maybe this formula is effective because there already has been a strong cultural shift against smoking — as strong, even, as the shift against excluding women from management positions?

Graphic addendum (disturbing image below)

Whether smoking in movies actually encourages young people to take up smoking is of course a not a settled issue — especially on websites sponsored by tobacco sellers, as seen in this ironic screen-shot from Smokers News:

One reason to have an explicit policy is that it’s easy to assume viewers will see through the glamour to the negative outcomes. “Surely no one will want to be like that character…” But people – maybe especially young people? – have an amazing capacity to celebrate selectively from the characters they see. I have learned from experience that, in children’s stories, even those who get their comeuppance in the end still manage to emerge as role models for their bad behavior. So maybe some people want to relive this from Pulp Fiction…

…and aren’t put off by this:

—————————–

* “A new incident occurred each time 1) a tobacco product went off screen and then back on screen, 2) a different actor was shown with a tobacco product, or 3) a scene changed, and the new scene contained the use or implied off-screen use of a tobacco product.”