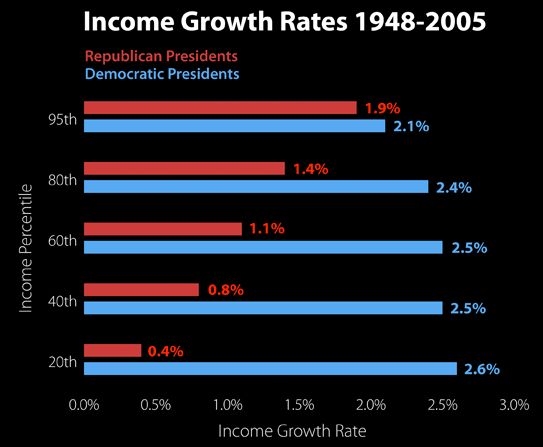

Tipped off by Dmitriy T.M., I enjoyed a Slate slideshow depicting and contextualizing the shrinking of the middle class and the growing advantage of the very top earners in the U.S. over time. We’ve highlighted this slideshow before, but I thought this image deserved its own post. Drawing on data from 1948 to 2005, put together by Larry Bartels, Slate shows that all income brackets prosper under both Democratic and Republican leadership, despite the idea that Republicans are fiscally responsible and Democrats irresponsible. Under Democrats, however, nearly everyone is much more prosperous. The highest income brackets are, given the margin of error, equally prosperous and all other brackets are significantly more so.

The figure reminds us that stereotypes about Republicans and Democrats don’t reflect reality and economic prosperity isn’t a zero sum game.

More slides at Slate.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.