Human beings are prone to a cognitive bias called the Law of the Instrument. It’s the tendency to see everything as being malleable according to whatever tool you’re used to using. In other words, if you have a hammer, suddenly all the world’s problems look like nails to you.

Objects humans encounter, then, aren’t simply useful to them, or instrumental; they are transformative: they change our view of the world. Hammers do. And so do guns. “You are different with a gun in your hand,” wrote the philosopher Bruno Latour, “the gun is different with you holding it. You are another subject because you hold the gun; the gun is another object because it has entered into a relationship with you.”

In that case, what is the effect of transferring military grade equipment to police officers?

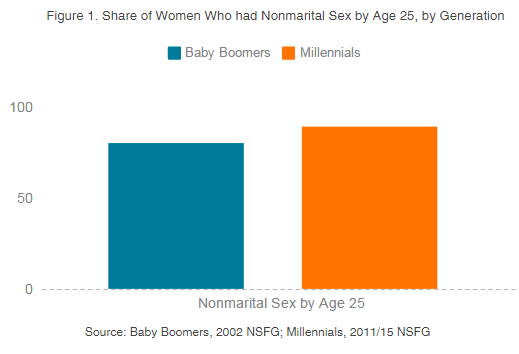

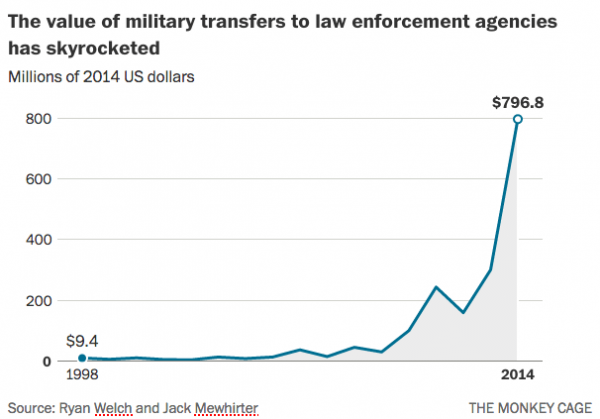

In 1996, the federal government passed a law giving the military permission to donate excess equipment to local police departments. Starting in 1998, millions of dollars worth of equipment was transferred each year. Then, after 9/11, there was a huge increase in transfers. In 2014, they amounted to the equivalent of 796.8 million dollars.

Image via The Washington Post:

Those concerned about police violence worried that police officers in possession of military equipment would be more likely to use violence against civilians, and new research suggests that they’re right.

Political scientist Casey Delehanty and his colleagues compared the number of civilians killed by police with the monetary value of transferred military equipment across 455 counties in four states. Controlling for other factors (e.g., race, poverty, drug use), they found that killings rose along with increasing transfers. In the case of the county that received the largest transfer of military equipment, killings more than doubled.

But maybe they got it wrong? High levels of military equipment transfers could be going to counties with rising levels of violence, such that it was increasingly violent confrontations that caused the transfers, not the transfers causing the confrontations.

Delehanty and his colleagues controlled for the possibility that they were pointing the causal arrow the wrong way by looking at the killings of dogs by police. Police forces wouldn’t receive military equipment transfers in response to an increase in violence by dogs, but if the police were becoming more violent as a response to having military equipment, we might expect more dogs to die. And they did.

Combined with research showing that police who use military equipment are more likely to be attacked themselves, literally everyone will be safer if we reduce transfers and remove military equipment from the police arsenal.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.