Assigned: Life with Gender is a new anthology featuring blog posts by a wide range of sociologists writing at The Society Pages and elsewhere. To celebrate, we’re re-posting four of the essays as this month’s “flashback Fridays.” Enjoy! And to learn more about this anthology, a companion to Wade and Ferree’s Gender: Ideas, Interactions, Institutions, please click here.

Assigned: Life with Gender is a new anthology featuring blog posts by a wide range of sociologists writing at The Society Pages and elsewhere. To celebrate, we’re re-posting four of the essays as this month’s “flashback Fridays.” Enjoy! And to learn more about this anthology, a companion to Wade and Ferree’s Gender: Ideas, Interactions, Institutions, please click here.

.

“Tits,” by Matt Cornell

Of the many nicknames I’ve acquired over the years, there’s one I’m reminded of today. The name was given to me by a bully shortly after I entered the sixth grade. I had been a fat kid since elementary school, but as puberty began to kick in, parts of me started growing differently than expected. The doctors said I had gynecomastia. “Man boobs,” or “moobs” in the jeering parlance of our popular culture.

But my bully simply called them “tits.” And so this also became my name in the school hallways.

I was Tits.

He would pass me in the hall and catcall “Hey Tits!” and his buddies would laugh. Sometimes, if he was feeling extra bold, he might actually grab one of my breasts, and squeeze it in front of the other kids. Not everyone laughed. But many did.

As direct as this bullying was, growing up with gynecomastia was characterized by smaller insults. Most kids would just ask “Why don’t you wear a bra?” Even adults could be cruel. “Are you a boy or a girl?” I was often asked.

When wearing shirts, it was crucial that they be loose fitting. If a T-shirt had shrunk in the dryer, I would spend hours and days stretching it out, so that it didn’t cling to my body. You can see fat boys do this every day. Pulling at their shirts to hide the shape of their bodies, but particularly their breasts.

As a fat kid, and one who hated competition, I learned to loathe sports, and especially, physical education. The one form of exercise which I enjoyed from childhood was swimming. Unfortunately, as my breasts grew, so did my shame about removing my shirt. At summer camp, I never set foot in the swimming pool. I knew that taking off my shirt would bring ridicule, and that leaving it on while swimming would show that I felt ashamed of my body. So, I pretended that I was above swimming — that I was too cool for the pool.

By high school, I had developed remarkable powers of verbal self defense. I absorbed cruelty and learned how to mete it back out in sharp doses. There’s no doubt that this shaped the person I became, for better and for worse. In high school, I managed to carve out a social niche for myself. The bullying stopped. But the shirts stayed loose-fitting. I rarely went swimming.

The doctors thought that perhaps I suffered from low testosterone. I found this funny, since my sex drive had been in high gear since the time I was a sophomore. I assured them that this was not the case. Finally, the doctors said that my excess breast tissue was probably just a result of being fat. Lose the weight and the breasts will go away.

So I lost weight. I don’t remember how much. But by senior year, I was slender. Girls were starting to talk to me. I was more confident. And I still had breasts. After graduation, the doctors congratulated me on my thin body. Now it was time to get rid of my breasts.

In the first surgery, I was placed under general anesthesia. The doctor made a half moon incision under each nipple and cut out the excess breast tissue, finishing the job with some liposuction. Unfortunately the surgery wasn’t a complete success. My breasts were smaller, but lumpy, and my nipples were puckered. It took a second surgery to make everything look “normal.”

I was nineteen. On New Year’s Eve, I went to a party and got drunk for the first time in my life. There, I met a girl who took my virginity. She was too drunk to insist on taking my shirt off. This was a relief, because under my shirt was a sports bra, and under that layers of gauze. My chest was still healing from the second surgery. In many senses of the word, I was still becoming a man.

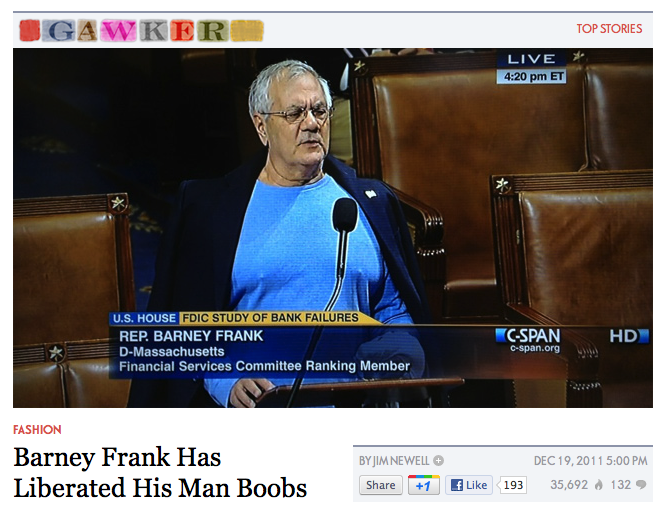

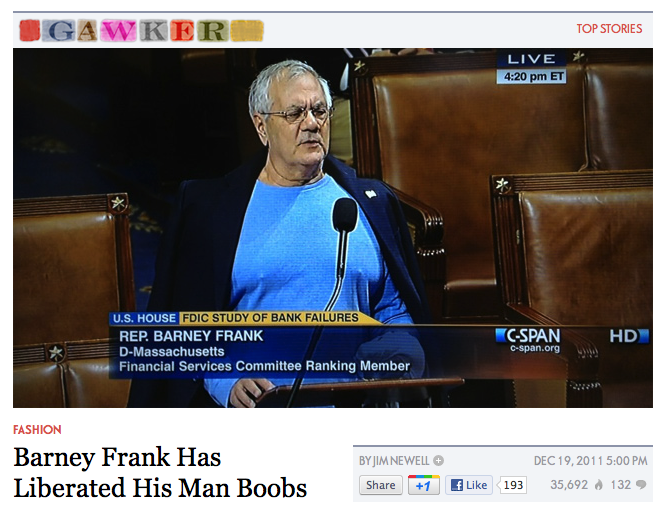

I’m reminded of this recently, oddly enough, after reading one of those “humorous” snarky news stories that pop up in the right column of The Huffington Post. Perhaps you’ve seen the photo making the rounds. It’s of Barney Frank’s “moobs.” The photo inspired similar stories at gay culture site Queerty, Gawker and Slate, which used the incident as the pretense for a scientific column.

While all of these nominally liberal sites pay lip service to the dignity of gay and transgender people, they miss one thing that is very clear to me. Aside from the obvious fat shaming in these stories, the fixation on “man boobs” reveals our culture’s obsession with binary gender. As I noted on The Huffington Post’s comment thread, before a moderator whisked my comment away, “the only breasts The Huffington Post approves of are those of thin, white female celebrities.”

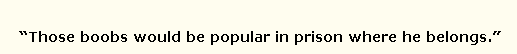

Here’s one of the many comments Huffpo didn’t delete:

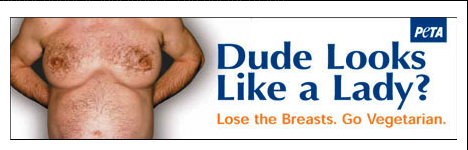

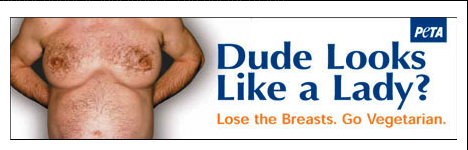

It’s culturally ubiquitous. PETA, for example, is a habitual offender:

Men are supposed to have flat chests, hairy bodies and big penises. Women are supposed to have large breasts, thin hairless bodies and tidy labias. (If a woman’s labia are too big, it just might remind us that, with a little testosterone, the same tissue would make a penis.)

We have all the evidence we need that biological sex and gender are not as rigid or fixed as we imagine. There are intersexed people. There are transgender people and genderqueer people. There are millions of men and boys like me, who also have large breasts, or gynecomastia, a medically harmless (though socially lethal) condition that your insurance just might pay to correct. The prevalence of gynecomastia in adolescent boys is estimated to be as low as 4% and as high as 69% . As one article notes: “These differences probably result from variations in what is perceived to be normal.” You think?

We’re so entrenched in that snips ‘n snails bullshit, that we can’t accept bodies which don’t fall on either extreme of the gender continuum. Transgender men and women encounter these attitudes in direct, and sometimes life-threatening ways. And, given the misogyny that pervades our society, these pressures are even harder for women and girls, whether they’re cisgender or transgender. Their bodies are hated and desired in equal measure. When my bully grabbed my breasts and called me “Tits,” he was taking what he wanted. He was also reminding me that I was no better than a girl. I was beneath him.

With the explosion of social media and the surveillance society, body policing has gotten much more intense. We live in an age of crowdsourced bullying. I cannot imagine what it would be like to grow up as a boy with breasts in 2011. I suppose I’d spend hours in Photoshop digitally sculpting my body, to remove fat from my face, belly and chest before uploading my profile photos. If I were a fat girl, I might become very skilled at using light and angles to disguise my less than ideal body, to avoid being dubbed a “SIF” or “secret internet fatty,” by my tech-savvy peers. I would probably become vigilant about removing tags from unflattering photos and obsess over remarks people made about me on comment threads.

Twenty years have gone by, and I miss my breasts. As a chubby adult male, I still have a small set of breasts, but not the ones I was born with. The two surgeries also deprived my nipples of their sensitivity.

I’ve often joked that if I knew I was going to become a performance artist, I would have kept my breasts. The breasts I have now are smaller, but still capable of stoking the body police. I once scandalized a fancy pool party in Las Vegas simply by taking off my shirt. I realize that, as a man, it is my privilege to do so. In most parts of our society, it is either illegal or strongly frowned upon for a woman to go topless. (Female breasts are either for maternity or for male sexual pleasure, not for baring at polite parties.) Perhaps my breasts, which remind people of this prohibition, invite a similar kind of censure.

I’ve performed naked enough in my adult life to know that the body police can always find a new area to target. I was recently stunned to hear porn actress Dana DeArmond describe me during a podcast interview as a “fat lady” while her host Joe Rogan openly theorized that my small penis was somehow connected to my feminism. Rogan’s view of gender is so restrictive that he can only conceive of male feminism if it is in a feminized body. (This is probably also why men who support feminism are often dubbed “manginas” by misogynists.)

There might actually be tens of thousands of words devoted to describing my fat body and small penis on the internet. It’s almost a point of pride. Now, I don’t just use my sharp tongue for self defense. I also use my body itself, as an argument, and as a provocation.

I am Tits. Got a problem with that?

Originally posted at My Own Private Guantanamo. Posted at Sociological Images in 2012. Cross-posted at Adios Barbie and Jezebel.

Matt Cornell is an artist, performer and film programmer who lives and works in Los Angeles. You can follow him on twitter at @mattcornell.