Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

Forty years ago Richard Easterlin proposed the paradox that people in wealthier countries were no happier than those in less wealthy countries. Subsequent research on money and happiness brought modifications and variations, notably that within a single country, while for the poor, more money meant fewer problems, for the wealthier people — those with enough or a bit more — enough is enough. Increasing your income from $100,000 to $200,000 isn’t going to make you happier.

It was nice to hear researchers singing the same lyrics we’ll soon be hearing in commencement speeches and that you hear in Sunday sermons and pop songs (“the best things in life are free”; “mo’ money mo’ problems”). But this moral has a sour-grapes taste; it’s a comforting fable we non-wealthy tell ourselves all the while suspecting that it probably isn’t true.

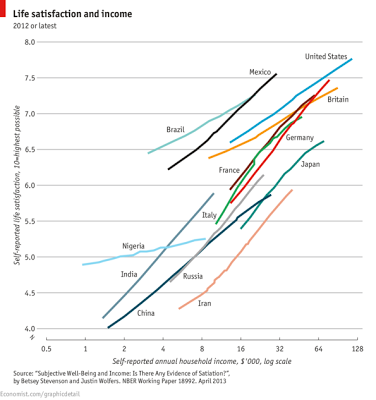

A recent Brookings paper by Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers adds to that suspicion. Looking at comparisons among countries and within countries, they find that when it comes to happiness, you can never be too rich.

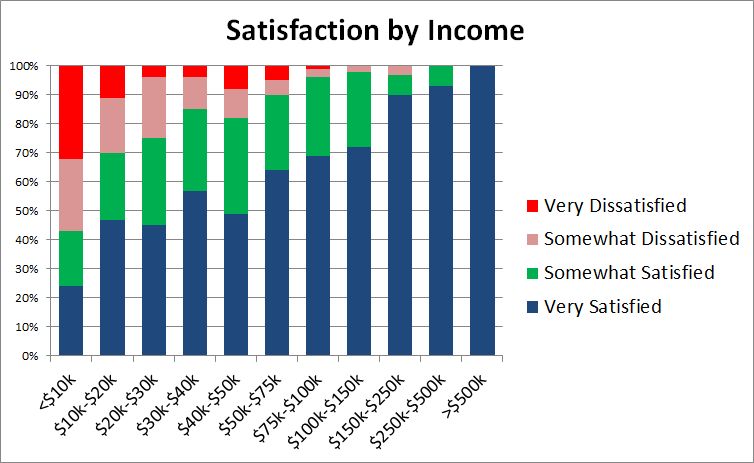

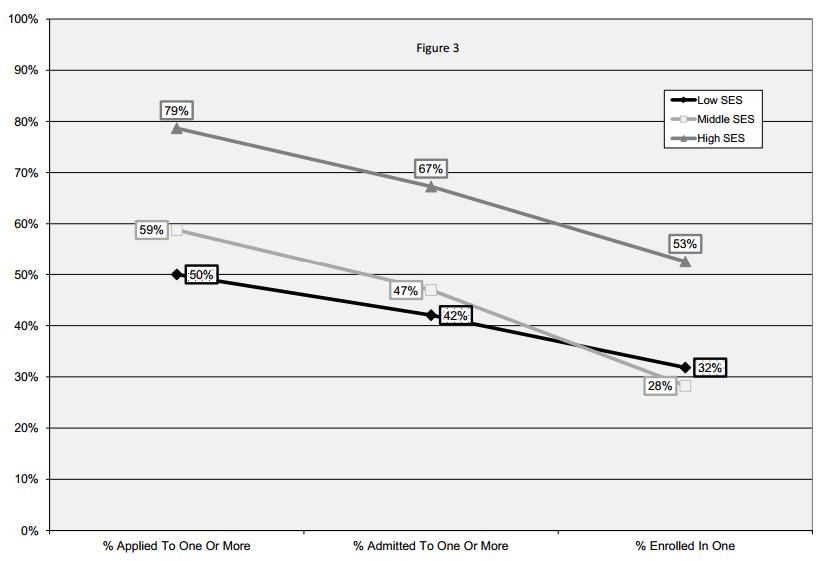

Stevenson and Wolfers also find no “satiation point,” some amount where happiness levels off despite increases in income. They provide US data from a 2007 Gallup survey:

The data are pretty convincing. Even as you go from rich to very rich, the proportion of “very satisfied” keeps increasing. (Sample size in the stratosphere might be a problem: only 8 individuals reported annual incomes over $500,000;100% of them, though, were “very happy.”)

Did Biggie and Alexis get it wrong?

Around the time that the Stevenson-Wolfers study was getting attention in the world beyond Brookings, I was having lunch with a friend who sometimes chats with higher ups at places like hedge funds and Goldman Sachs. He hears wheeler dealers complaining about their bonuses. “I only got ten bucks.” Stevenson and Wolfers would predict that this guy’s happiness would be off the charts given the extra $10 million. But he does not sound like a happy master of the universe.

I think that the difference is more than just the clash of anecdotal and systematic evidence. It’s about defining and measuring happiness. The Stevenson-Wolfers paper uses measures of “life satisfaction.” Some surveys ask people to place themselves on a ladder according to “how you feel about your life.” Others ask

All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?

The GSS uses happy instead of satisfied, but the effect is the same:

Taken all together, how would you say things are these days – would you say that you are very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?

When people hear these questions, they may think about their lives in a broader context and compare themselves to a wider segment of humanity. I imagine that Goldman trader griping about his “ten bucks” was probably thinking of the guy down the hall who got twelve. But when the survey researcher asks him where he is on that ladder, he may take a more global view and recognize that he has little cause for complaint. Yet moment to moment during the day, he may look anything but happy. There’s a difference between “affect” (the preponderance of momentary emotions) and overall life satisfaction.

Measuring affect is much more difficult — one method requires that people log in several times a day to report how they’re feeling at that moment — but the correlation with income is weaker.

In any case, it’s nice to know that the rich are benefitting from getting richer. We can stop worrying about their being sad even in their wealthy pleasure and turn our attention elsewhere. We got 99 problems, but the rich ain’t one.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.