Who’s afraid of a global pandemic? We all are, at the moment. But like so many other forms of fear, concern about medical issues is much more acute for people in precarious and vulnerable social positions. The privileged—particularly those who are white and upper class—can more afford not to be preoccupied with health and medical concerns, including pandemics.

In our new book Fear Itself, we found consistent support for updating our classic theories about vulnerability. Classic theories often understand vulnerability in physical terms. But risk and vulnerability are also social, rather than primarily physical, and we found consistent evidence that members of disadvantaged status groups—particularly women, racial and ethnic minorities, and those with lower levels of social class—had higher levels of fear across many domains.

Using pooled data from six waves (2014–2019) of Chapman Survey of American Fears (CSAF), we examined the sociological patterns of fears about disease and health. We looked at fear about four specific issues: global pandemics, fears of becoming seriously ill, and fears about people you love becoming seriously ill or dying.

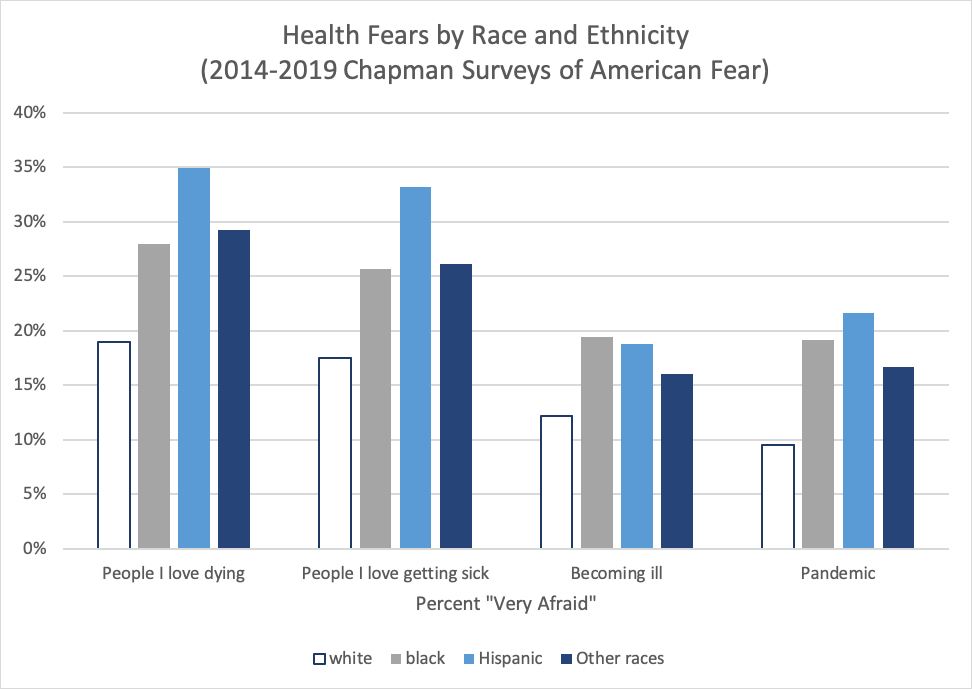

The racial and ethnic disparities across these four outcomes are striking, with white Americans being significantly less likely to report being “very afraid” of pandemics and medical issues involving themselves or their families. Hispanic Americans reported the greatest concern about all four issues, likely a reflection of lower rates of health care insurance and access among Latino/a communities and individuals.

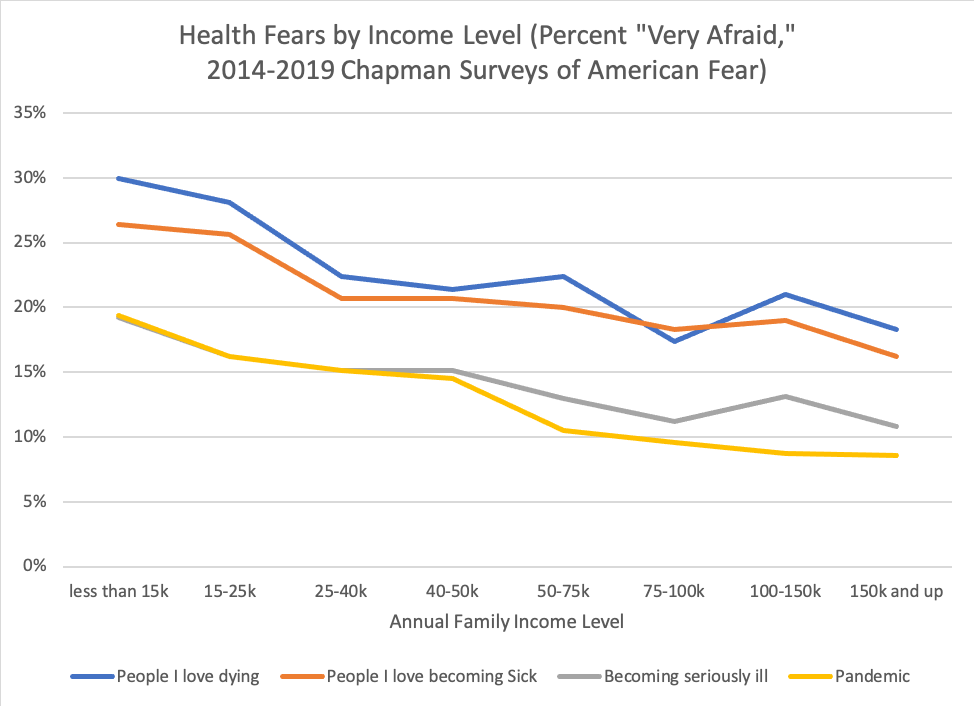

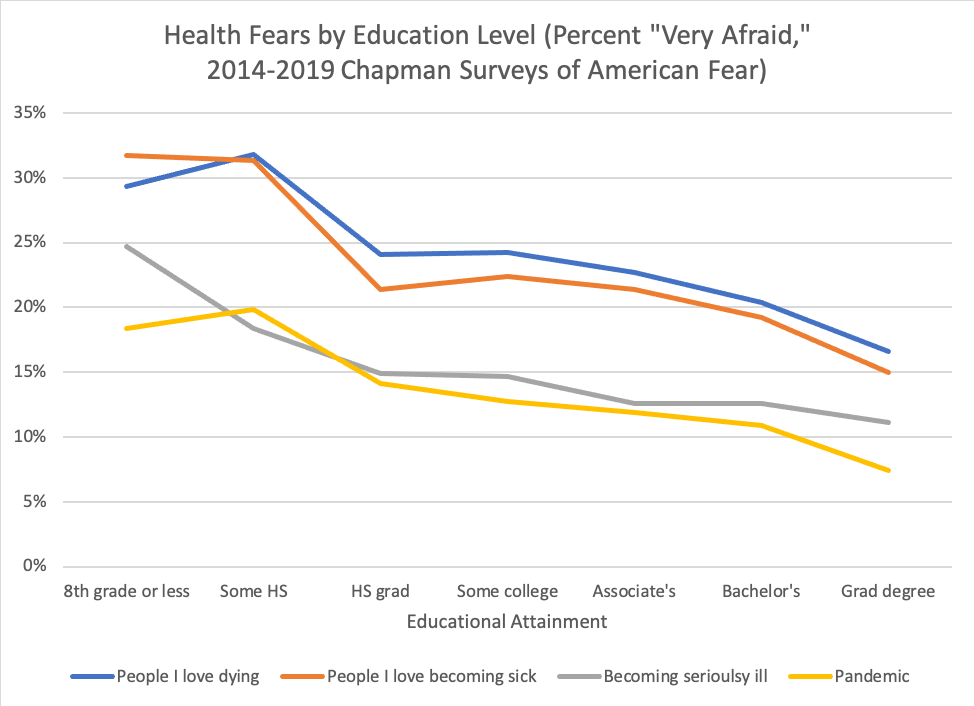

Likewise, we find clear disparities in fears about health and pandemics across different levels of education and family income. Again, the mechanisms are clear, with vast disparities in health care access in the United States, as well as the well-known social determinants of disease both playing a role.

While these patterns are not necessarily surprising, they are nonetheless disconcerting, for a number of reasons. First, in terms of the epidemiology of the Coronavirus pandemic, it is the disempowered who will disproportionately bear the brunt of the negative health effects, and who will be least equipped with the resources to adequately respond if and when they get sick. Second, when preventative public health measures such as quarantines are put in place, it is people in the working and lower classes who can least afford to take time off of work or keep their children home from school in order to comply with public health procedures.

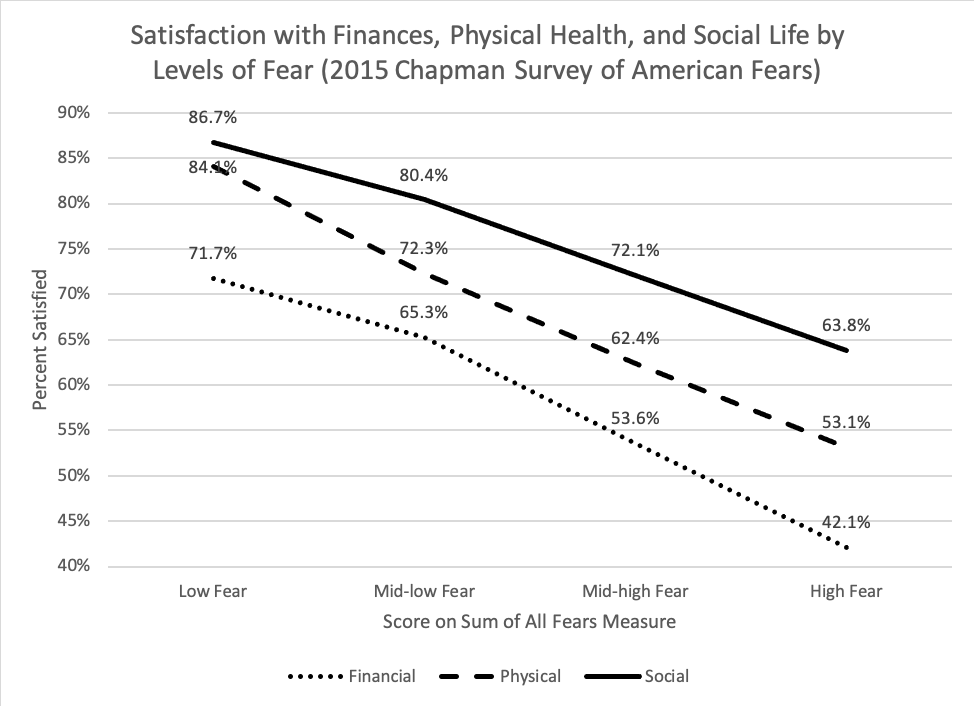

Not only does fear disproportionately prey upon people in less powerful social positions, it also exacerbates and deepens inequality. Higher levels of fear and anxiety are strongly and significantly related to harmful health outcomes, even after accounting for the social inequalities that structure who is afraid in the first place. In Fear Itself we created an omnibus fear metric we called the “Sum of All Fears” that combined levels of fear across a wide range of domains, including but not limited to health, crime, environmental degradation, and natural disasters. Scores on this global, summary fear metric once again produced strong support for social vulnerability theory; but levels of fear were also strongly connected to steep declines in quality of life across a range of domains, including social, personal, and financial well-being.

Taken together, fear is both a reflection of and a source of social inequality. This is true for the current global Coronavirus pandemic and the accompanying concerns, but it will also be the case long after the pandemic has passed. Our hope is that sociologists, social psychologists, and public health officials begin to consider how fear factors into and deepens social inequality.

Joseph O. Baker is Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at East Tennessee State University and a senior research associate for the Association of Religion Data Archives.

Ann Gordon is Associate Professor of Political Science and Director of the Ludie and David C. Henley Social Science Research Laboratory, Chapman University.

L. Edward Day is Associate Professor and Chair of the Sociology Department at Chapman University.

Christopher D. Bader is Professor of Sociology at Chapman University and affiliated with the Institute for Religion, Economics and Culture (IRES). He is Associate Director of the Association of Religion Data Archives (www.theARDA.com) and principal investigator on the Chapman University Survey of American Fears.

Comments 245

Katherine — March 23, 2020

Thanks for the post

Best regards

Katherine

Koribv — March 27, 2020

Hello men, I believe that actually for you at the moment than trying to find wonderful ways for healing than any other thing. This you get Cannabidiol oil wonderful information that can help you and cbd-oil-reviews.org/ your closest friends. I believe in fact that this is a wonderful probability for such a thing to exist and not to think on the topic of their own difficulties

Kylie — March 27, 2020

Hello, I think that this is a very important thing to bring attention to, as helping our neighbors and those in need is essential during compromising times like this.

Welodas — March 28, 2020

Hi guys, I think you should tell me about the fact that you want to know that there is the most effective way that you can forget about real back pain and pain in your joints. There is an excellent Cannabidiol oil this will help you do something bestofcbdoilreviews.com that you will not heal but it will help you. I think you can live without pain and do not get sick

woleswil — March 29, 2020

Have you heard anything about CBD? CBD (cannabidiol) is a natural chemical found in cannabis flowers. CBD is one of over 60 different cannabinoids. And one of the more than 400 natural substances found in cannabis plants. You can also see more information here selectcbdoil.net/! Does it scare you that it is oil on cannabis? you need to read more because it can make you happy, since Canabis Oil does not cause affection!

Dennis Kemp — March 30, 2020

I figure you should inform me regarding the way that you need to realize that there is the best way that you can disregard genuine back torment and torment in your joints. I put Custom Essays UK stock in truth this is a great likelihood for something like this to exist and not to think on the subject of their own challenges

Katherine — March 31, 2020

Thank you for sharing this. If you need some more information I would suggest you visit here.

Vladimir Serdukov — April 1, 2020

Hemp vegetation are rich in CBD and reduced THC, plus, in 2018, CBD products that contain fewer than zero. 3% THC and therefore are extracted from hemp plants have been created legal across the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

CBD oil is made by simply extracting CBD from typically the cannabis or hemp plant lifestyle and then mixing that with a carrier for example MCT oil. Other CBD oil infused products consist of capsules, gummies and ointments.

Find out more hande details via

cbdoilbrands.org/

Derty567 — April 3, 2020

Few people know that cannabis pills can help get rid of addiction. No matter how strange it sounds - it is. The possibilities of using cannabidiol for the treatment of alcohol dependence are currently being studied. After all, it is known that severe anxiety and the risk of seizures are the main troubles with alcohol detoxification, and CBD https://cbdoiler.net/ is the best suited to relieve these symptoms .

Derty567 — April 3, 2020

Few people know that cannabis pills can help get rid of addiction. No matter how strange it sounds - it is. The possibilities of using cannabidiol for the treatment of alcohol dependence are currently being studied. After all, it is known that severe anxiety and the risk of seizures are the main troubles with alcohol detoxification, and CBD https://cbdoiler.net/ is the best suited to relieve these symptoms .

Steven — April 7, 2020

Everything is now on the search for perfect medicines Cannabidiol oil for your body. And using this opportunity, I would strongly wish for you all to recommend a wonderful website that can suit you as a pretty https://whatscbd.org successful person. I believe in fact that you simply can create wonderful things. I believe that you will find a very good drug there

Mark Brown — April 7, 2020

Hi, I recommend an essay writing resource https://www.essay-company.com/apa-style-formate that will do all the work for you quickly and efficiently.

pikachu chu — April 12, 2020

Prevent covid-19 disease by wearing a mask when going out, washing your hands often with soap, cleaning the house to limit the virus. powerline io

Samantha Ellis — April 22, 2020

While nature is fortunate, the next pandemic-potential flu virus will grow somewhere fast to capture and contain the threat — a nation with strong public health service and well-stocked hospitals. Unless we're unfortunate, a novel, deadly and highly infectious flu virus will break out in crowded, vulnerable megacities that lack the infrastructure for public health. A rapidly changing virus might burst out in a city and ride pillion with foreign tourists before health authorities know what is going on. so we guys running a campaign on this lockdown to helping students in their coursework from the best essay writer at many affordable prices.

james tinker — April 24, 2020

added that since every low-income family forced to withstand higher exposure risks may infect others, the consequences of inequality (most notably the poor feel) “put the entire society at risk.” By: university law essay writing service

Hafsa — April 28, 2020

Thanks for the wonderful share. Thanks for sharing invaluable knowledge with all of us, I feel strongly that love and read more on this topic. Looking to reading your next post. Brilliant post. Keep up the very excellent work. teletalkbd.

Jon Curtis — May 7, 2020

Thanks for sharing this information Great work. codeboks

PureKana gummies for pain — May 11, 2020

Have you tried PureKana gummies for pain? Some people claim that they work. I haven’t tried yet, but I am going to buy one day to try.

Valerie D. Kohler — May 16, 2020

Well i guess all of us are! Make this fear go away by keeping yourself occupied by studying, reading articles or playing games!! you can check my review on android apps and decide which one is best for you.

ilamariya — May 18, 2020

good

ilamariya — May 18, 2020

good click

ivaanadam — May 18, 2020

Glad to see this post and it is very informative too. You gave a detailed description of social Inequality. peer to peer car sharing The link you have shared also useful and this graph representation makes this post more understandable. It is a very useful post too.

Sania — September 14, 2020

He's still Mike Tyson, he's still one of the strongest, most explosive people who ever touched a boxing ring Roy Jones vs Mike Tyson Live. If anything, I made a mistake going in with him. He's the bigger guy, he's the explosive guy.

Freya Murray — October 15, 2020

The process of writing a professional APA interview paper is rather troublesome and time-consuming, especially for the individual, who do not possess excellent writing skills or do not have relevant experience. We recommend getting the assignment help in this case https://primeessay.org/apa-interview-paper.html

Kirdat — October 17, 2020

Joshua says he doesn’t even really want to talk too much about Fury at this time, not looking to piggyback off his name while he’s headed towards an IBF title defense against Anthony Joshua vs Kubrat Pulev Live.

Hares Werev — October 17, 2020

There are remarkable young people who are planned today to get an incredibly astonishing juvenile who will get your thought. In like way, you will have the decision to live in complete love and concordance. So you can singles over 40 dating sites endeavor to examine creation a future family. I figure you should try to appreciate all the energizing youngsters who long for you and fundamentally talk with you

Edward — October 28, 2020

Now thats really interesting

Hanna Mariotti — October 30, 2020

Hello! I believe that a family is, first of all, caring for each other, and not just having children. We try to give children and husband / wife the best education, care and comfort. My whole family uses the services of https://dentatur.com/ - it's a real show of care. I can trust the dentists of this clinic to take care of my teeth, but most importantly, I can trust my family to these specialists.

resultbd — December 13, 2020

After submitting the HSC Roll and Registration Number on this website, your result will show. You can also see your HSC Result mark sheet by visiting this link of the Ministry of Education website

Lilia Buergel — December 21, 2020

Jual Beton Cor umumnya dicari oleh para pekerja dalam bidang bangunan. Beton cor ialah salah satu bahan bangunan yang mempunyai... info lebih detail http://pagarpanelmegacon.kedungsepur.my.id/2020/08/harga-pagar-panel-beton-megacon-di_23.html

Kasey Plump — December 21, 2020

Toilet phenolic WC ini juga banyak sekarang untuk gedung komersial seperti sekolah. Memakai kamar kecil phenolic kamar kecil hal yang ... tap https://toiletpartisi.blogspot.com for detail information.

Monica Dennis — December 28, 2020

Such studies are quite popular during a pandemic. But still, society hopes for positive predictions. Personally, I try to devote more time to my hobby, I have the opportunity to do so thanks https://essaysleader.com/ideas-for-creating-an-effective-powerpoint-presentation/

joshua — December 28, 2020

Great News, In this Saturday The Most wanted and exciting Boxing Match between “Floyd Mayweather” and “Logan Paul” Full Fight????Boxing ON Air is set to open the season on Saturday, February 20 in USA.

Hermelinda Maravilla — December 29, 2020

Laman perusahaan kontraktor kolam renang berpengalaman dan terpercaya. Terbaik dalam pembuatan, instalasi, renovasi, pembenaran, perawatan .... klik https://mozaik-kolamrenang.netlify.app/pasang-mozaik-kolam-renang-batu.html untuk lebih lengkap

Vi Culbreth — January 4, 2021

Partisi kamar mandi kubikal yakni salah satu desain kamar mandi ialah ini yang saat dimanfaatkan untuk dapat bangunan minimalis. Dia termasuk pembatas kamar ... tap https://medium.com/@toiletcubiclephenolic/sewa-toilet-portable-depok-kloset-duduk-jongkok-termurah-higienis-4bf89776ba32 for detail.

Tisa Sharrow — January 6, 2021

Enjoy the professional towing service you expect with fully trained representatives utilizing our preferred tow provider network to tow your vehicle to the trusted ... visit https://carcarrier.netlify.app/car-carrier-medan-jakarta.html for detail

Zenobia Cousens — January 7, 2021

Kaca tempered harga murah untuk dinding, pintu, partisi, canopy produk dari KacaTempered.co.id tersedia disini dengan jasa pasangnya.Kaca Tempered yaitu ... info lebih lanjut https://railing-kaca-murah.blogspot.com/2019/10/jual-railing-kaca-tempered-1-pandeglang.html

HSC Result 2020 — January 9, 2021

Thanks for your information about HSC Result 2020 now.

economics assignment — January 10, 2021

High quality microeconomic Assignment Help at highly competitive rates. Get microeconomics assignments prepared by highly qualified professionals and score high grades on all your assignments.

https://www.totalassignmenthelp.com/microeconomics-assignment-help

Josiah Verdejo — January 18, 2021

Epoxy is a large and heat painful and sensitive material. The gel time (time it takes the combined epoxy resin and hardener to originally harden up) can vary drastically depending on... visit https://jasawaterproofingcoating.blogspot.com/2019/12/jasa-waterproofing-coating-batu.html for more info.

HSC Marksheet — January 22, 2021

This is a Great Content. The HSC, Alim and Its Equivalent Exam Result will be Published last week of January 2021. The Results can be known through https://resultbangladesh.com/hsc-result

Arnetta Albano — January 25, 2021

DistributorPintu.com is mostly a aluminum security doors manufacturer that's even fashioned & produced industry-leading actual stability products, click https://pabrikpintualuminium.blogspot.com/2020/04/jual-pintu-alumunium-kusen-alumunium-1_14.html for detail.

Anonymous — January 28, 2021

Classic theories often understand vulnerability in physical terms. But risk and vulnerability are also social, rather than primarily physical, and we found consistent evidence that members of disadvantaged status groups. https://hashalot.io/blog/majning-efira-i-altkoinov-na-1080-i-ti-podschet-dohodnosti-nastrojka-majninga-i-razgon/

Anonymous — January 28, 2021

Higher levels of fear and anxiety are strongly and significantly related to harmful health outcomes, even after accounting for the social inequalities that structure who is afraid in the first place. https://cryptograph.life/reviews/cryptocurrencies/obzor-kriptovalyuty-vechain-vet-osobennosti-prognoz-kursa-i-perspektivy .

SSC New Short Syllabus — February 2, 2021

Bangladesh University of Professionals BUP Admission Information is available on https://resultbangladesh.com/bup-admission. You will be found Here Bangladesh University of Professionals Admission Circular, Admit Card, Seat Plan, Marks Distribution and Admission Test Result information.

SSC Short Syllabus 2021 PDF Download — February 2, 2021

Military Institute of Science and Technology MIST Admission Information is available on https://resultbangladesh.com/mist-admission. You will be found Here Military Institute of Science and Technology Admission Circular, Admit Card, Seat Plan, Marks Distribution and Admission Test Result information.

SSC Short Syllabus 2021 — February 2, 2021

For Khulna University of Engineering and Technology Admission, visit https://resultbangladesh.com/kuet-admission and find all update information.

SSC Short Syllabus 2021 — February 4, 2021

Very nice and helpful post for us. Thank you very much for this article,

SSC Short Syllabus 2021 — February 4, 2021

Check now https://bdexamresults.com/ssc-short-syllabus-update

https://bdexamresults.com/dakhil-exam-new-syllabus

Result in Bangladesh — February 6, 2021

For Begum Rokeya University BRUR Admission information and updates, visit official website of Begum Rokeya University, Rangpur brur ac bd.

https://essays-service.com/ — February 8, 2021

Don't know what to write and how to submit your essay? I think you are on the right track! So look https://essays-service.com/how-to-write-a-conclusion-for-dissertation.html I think you'll like it. Pass your essay perfectly and you will relax with ease!

Hafsa — February 13, 2021

Very likely I’m want to bookmark your blog. You surely come with remarkable stories. Many thanks for sharing with us your web site. ngo jobs 2021.

Medical Admit Card and Seat Plan — March 2, 2021

Bangladesh Dhaka Islamic University of Technology Admission Result has been Published for Islamic University of Technology Undergraduate Programs.

amun — May 4, 2021

The information you give is so valuable to me, I will visit your website more often. paper io 2

gst admission result 2021 — May 4, 2021

Every students download her Dhaka University Admit card and also know admission test final result.

Manik — May 4, 2021

sit official website of GST University, gstadmission.ac.bd gst admission result so all unit admission process and payment instruction download.

Василий Семерик — May 19, 2021

Ого пельмени вы тут наспамили!! Линкбилдеры чи шо?

Ось завод хароши по плитки на http://www.plitka.kharkov.ua/

http://www.plitka.kharkov.ua/

NU Coronavirus Vaccine Registraton — July 13, 2021

For Corona Virus Vaccine Registration of National University Students for covid, Nu run a website http://103.113.200.29/student_covidinfo/. Students can be Provide their Vaccine Related information through this web.

sepehrsoule — July 31, 2021

I am in fact pleased to read this weblog posts which contains lots of helpful information,

thanks for providing such information.

souleh price

artifical grass — July 31, 2021

I do not know what to say really what you share very well and useful to the community, I feel that it makes our community much more developed, thanks

قیمت سوله

سوله مرغداری

pamchalpaint — July 31, 2021

Thank you so much for this wonderful post, very useful and informative.

pamchalpaint — July 31, 2021

Thank you so much for this wonderful post, very useful and informative.

رنگ دریایی

takgrass — July 31, 2021

قیمت چمن مصنوعی

atlaschaman — July 31, 2021

قیمت چمن مصنوعی

mason ethan — September 10, 2021

Searching for the Political science assignment help online? Then you are at the right place. Our team of professionals is highly proficient in providing online help for Political science assignments.

Jenifer — September 12, 2021

The post is quite informative as I could derive a lot on the topic by reading through it. At MyAssignmentHelpNow, We Offer Pocket-Friendly assignment writing services. Students trust our online assignment help in Australia. To get genuine assignments within deadlines, Hire Us Today!

24newsdaily — September 13, 2021

I think this is an informative post and it is very useful and knowledgeable. It looks perfect and I agreed with the topics you just said. Thanks for the share. But if you guys want 24newsdaily then contact us.

Lilyi Hiyuston — October 1, 2021

Thin, bright, functional - that's what modern TVs are like. You won't surprise users with clear and contrasting images, so TV manufacturers are competing with might and main: either they increase the size and resolution of the screen even more, or they add power to the speakers. Is there any benefit to the consumer and how to choose the perfect device for watching a movie? A complete analysis of TVs from types of devices to the convenience of the PU is presented below https://insider.games/best-tv-for-bright-room/

Lilyi Hiyuston — October 1, 2021

Thin, bright, functional - that's what modern TVs are like. You won't surprise users with clear and contrasting images, so TV manufacturers are competing with might and main: either they increase the size and resolution of the screen even more, or they add power to the speakers. Is there any benefit to the consumer and how to choose the perfect device for watching a movie? A complete analysis of TVs from types of devices to the convenience of the PU is presented below https://insider.games/best-tv-for-bright-room/,

custom boxes — October 5, 2021

Great service and product of custom hair extension packaging. Thanks for your help throughout the process.

https://customboxesbulk.com/

custom boxes — October 5, 2021

hair extensions packaging box hold their own significance in the retail market as custom hair extension packaging are widely used by different audiences for their different hair beautifying needs.

MilaM22 — October 18, 2021

I started learning Javascript and HTML about 8 years ago. Recently I noticed that in the codes of some online gambling games, there are hints on how they work. That is, you can easily beat them, but I need help. You can look at the bovada welcome bonus and find a catch in the code.

MilaM2s — October 18, 2021

I have always felt sorry for medical students because of the complexity of their studies and the responsibility they then bear on themselves. That is why I couldn’t study to be a doctor, but chose the profession of an analyst. That is why I am doing analytics for german online https://onlinecasinoprofy.com/en/bovada-casino/ casinos. You can get a lot of useful information on this link that will help you to improve your financial situation a little.

MilaM2s — October 18, 2021

Before you know about the inherent function of Cryptocurrency gambling, it's essential to know what it actually is. If you've been making frequent trips to your favorite online casino, or if you've been making use of the traditional payment method such as credit cards, debit cards, or even wire transfers, then the idea of Cryptocurrency gambling may be a bit new to you. The majority of individuals aren't aware of the fact that they can make use of the web to do just about anything - from placing bets on sporting events to buying merchandise from online retailers to renting fancy cars. Now, thanks to the advent of Cryptocurrency gambling, people are able to do all of these things with the help of virtual or online currencies. https://onlinecasinoprofy.com/en/bovada-casino/

jeckysay — October 22, 2021

Best buy hacks experts share the best products that you should buy. We're a team of savings professionals delivering the best deals, tips and tricks to help you save at your favorite brands, stores and restaurants.

jeckysay — October 22, 2021

Great Guest Posts makes the link-building process very smooth and predictable each month. We’re committed to maintaining transparency. Our professional outreach team examines all websites manually to avoid black-hat backlink farms and PBNs. You can buy guest posts for SEO in almost any niche possible.

elightsigns — October 27, 2021

Greetings! I simply want to offer huge thumbs up for the great stuff you have got here on this post. It looks perfect and I agreed with the topics you just said. Thanks for the share. But if you guys want Sign Shop in UK than contact us.

brownrhichard12 — November 17, 2021

Top education

brownrhichard12 — November 17, 2021

Total Assignment Help gives bestassignment answers online service here with experts specializing in a wide range of disciplines ensuring you get the assignments that score maximum grades.

Ontiva — November 25, 2021

YouTube videos have always been the craze, but in recent times Ontiva, people have expressed the desire to Ontiva download

videos so they can save them into their computer system. For a long while, it was practically complicated to convert and download videos. However, recently several online platforms have emerged where YouTube videos can now easily be converted from YouTube to MP4 the most common file format.Ontiva is an online service provider that deals with the conversion of YouTube videos to MP4 and other file formats as per your convenience and demand. It is an easy to use website which does not require the user to betech-savvy but is simple for even beginners.Download YouTube to MP4

Emma Sara — November 30, 2021

and Chapter 9: Strategy Review, Evaluation, and Control.and then type a one to two page question-hub paper concerning the topics that you believed where worth your reading and understanding. What was the most valuable thing that you learned and why? Management, Business Communication, and Intro to Business BEFORE CLASS AFTER business CLASS DURING CLASS Decision Sims, Videos, and Learning Catalytics DSMs, pre-lecture homework, eText Writing Space, Video Cases, Quizzes/ Tests MyLab Critical …

icloud account on windows — December 6, 2021

Some iCloud features have minimum system requirements. iCloud may not be available in all areas and iCloud features may vary by area. See the Apple Support article System requirements for iCloud.

create icloud account on android

shell shockers — December 6, 2021

I'm not sure what to say about what you give; it's very well-done and beneficial to the community, and I believe it helps to develop our community. Thanks.

برای شما — December 12, 2021

این روش برای دانستن قینت تیرآهن مناسب نیست

barotik — December 12, 2021

در زمان حال حاضر بهترین قیمت تیرآهن رو از ما بگیرید

finley jordon — December 21, 2021

HP printer provides you simple and handy printing experience within a few minutes. But, sometimes, you may encounter some printing concerns and complications while working on your HP printer.

www.hp.com/go/wirelessprinting

finley jordon — December 21, 2021

Canon IJ Setup process takes a few minutes in device installation and software installation.

canon ij setup

solve my assignment — December 24, 2021

If you are not able to solve your assignment due to lack of knowledge then you can visit our website nzassignmenthelp.com, here we provide you solve my assignment service. We have the best team of experts who will assist you to solve your assignment with 100% plag free at the best price.

Manfaat Jus Mengkudu — December 24, 2021

Manfaat Jus Mengkudu Jus mengkudu mengandung 10% vitamin C dunia. Mengkudu adalah sejenis buah yang berasal dari Indonesia, khususnya Malaysia dan Thailand, namun kini tumbuh di seluruh dunia. Mengkudu adalah salah satu buah yang dapat dikonsumsi untuk manfaat kesehatan, dan termasuk dalam kategori ini. Noni mengandung sejumlah besar antioksidan, sehingga bermanfaat bagi tubuh.

Registered translator — December 28, 2021

If you searching which translation service to choose. Use the assistance of singapore translators. we may help you with all types translation. We have a group of registered translator who deliver you well precise translation of academic documents with outstanding quality.

Essay writing services — January 3, 2022

Indeed a pleasure to see such an informed piece of article. It's really intriguing to note how students put a lot of effort to achieve the momentous. I came across such a situation in my graduation days when I was having a function at my home on one side and immediate submission date on the other. I felt like I will have to leave either of them, after all, I had put up a year of hard work to achieve this feat. Thanks to Jenny, my cousin who told me about the page Do My Essay I clicked the highlighted word she sent to me, once I told them my problem, they were not only ready to do essay help but also to do it at very short notice. Talking to them was like I was hanging out with my college friends. It was a great experience, for Essay writing services worked very responsibly and told me that I may go and attend my cousin’s engagement.

Monica Bellucci — January 28, 2022

google

Ella Williams — February 15, 2022

Here I am for the first time, and I found beneficial information. Very nice and well-explained article.

Uniswap Exchange | Blockchain Login

Singapore Translators — February 17, 2022

Nice post by Joseph O. Baker, Ann Gordon, L. Edward Day, and Christopher D. Bader on social inequality medical fears, and pandemics. If you are seeking translation help for medical record documents then you should choose Singapore translators. Our company is one among Singapore registered translation companies.

james — February 20, 2022

Thank you for sharing this article. It is an amazing post, I am really impressed by your post. It’s really useful.

ij.start.cannon

ij.start.canon

All tech download — March 3, 2022

Wonderful post admin thanks you

all tech download

AIMS English — March 6, 2022

AIMS English is an excellent English teaching, learning and practice center where we use unique training and studying methods in order to develop the level of English for all of our students. We have unique course materials and experienced tutors to make learning English as smooth and easy as possible.

AIMS English

bennydoll — March 9, 2022

Great Post! Keep it up the great work.

david — March 13, 2022

Very nice content, Thanks for this idea, keep it up!!

disney plus start | https //aka.ms/remoteconnect

kristin burger — March 15, 2022

I am accessible to supply substance or surveys on almost about anything point. I compose in a matter-of-fact way, but will cheerful to display any specific fashion asked.

iPhone X Screen Repair near me

rosa anderson — March 16, 2022

A good one about sociology. All the paragraphs and scales figures are completely defined the whole topic. This will take a big part to make an assignment. I will go through in details after complete my project of

shearling coats and jackets styles.

Beatrice Jordan — March 21, 2022

Greetings!

I read this article and found it very informative and useful. Thanks for giving such a wonderful informative information. I hope you will publish again such type of post.

Regards

Beatrice Jordan — March 21, 2022

Greetings!

I read this article and found it very informative and useful. Thanks for giving such a wonderful informative information. I hope you will publish again such type of post.

Regards

AmazingAir

Ronald Barnes — March 21, 2022

Greetings!

I read this article and found it very informative and useful. Thanks for giving such a wonderful informative information. I hope you will publish again such type of post.

Regards

peter shawn — April 1, 2022

This is a really decent site post. Not very numerous individuals would really, the way you simply did. I am truly inspired that there is such a great amount of data about this subject have been revealed and you've put worth a valiant effort with so much class. Yeezy Gap Black Jacket

peter shawn — April 1, 2022

Outstanding article! I want people to know just how good this information is in your article. Your views are much like my own concerning this subject. I will visit daily because I know It will very beneficial for me Star Lord Jacket

peter shawn — April 1, 2022

Sincerely very satisfied to say,your submit is very exciting to examine. I never stop myself to mention some thing about it. You’re doing a remarkable process. Hold it up Only Murders In The Building Outfits

emmataylor — April 4, 2022

Sincerely very satisfied to say, your submit is very exciting to examine. I never stop myself to mention some thing about it. You’re doing a remarkable process. The Best Jacket gives you best opportunity to avail up to 60% OFF on Womens Biker Leather Jacket. Don't miss the sale.

ellen bella — April 6, 2022

Sincerely very satisfied to say, your submit is very exciting to examine. I never stop myself to mention some thing about it. The Last Dome is giving you different categories of article or blogging like technology movies and showbiz. If you want to read about it then visit this link.

قیمت سمپاش بنزینی — April 18, 2022

لیست سمپاش های بنزینی که برای زمین های کوچیک مناسب باشنو کجا میتونم پیدا کنم

VPN Suggestions Free — May 4, 2022

I am a short filmmaker and I like to make films for kids and young ones.

It is a nice profession and you may enjoy to work here. I am very happy. I design my own website and upload many animated films there. There is [url=https://www.vpnsuggestions.com/]VPN suggestions[url] It is too good and nice . You can enjoy its service for a long time. I experience that it is best VPN.

Suzzi Evens — May 10, 2022

I am in community of Assignment Writers UK and working as a writing expert at New Assignment Help, where students take Assignment Help UK. I wrote several assignments in my career and delivered all of them on time. If you are a student who is having trouble in writing assignments then I recommend you Write My Assignment UK service from an expert like us.

Kaylee Brown — May 11, 2022

Economics assignment helper can help you with all your assignment-related woes. You may get economics quiz assistance online, as well as assignments, exams, and midterms. Not only economics as the subject but all the three subcategories of economics that are microeconomics, macroeconomics, and managerial economics, are also grasped by our experts who have multiple years of experience. Plagiarism-free content written by assignment experts is guaranteed to give you the highest grades; this is our promise to you. We also have a very flexible policy if you choose to examine. But rest assured that our service is sure to leave you satisfied.

sas asasa — June 6, 2022

I wrote several assignments in my career and delivered all of them on time. If you are a student who closest apple bank near me is having trouble writing assignments then I recommend you Write My Assignment UK service from an expert like us.

me — June 12, 2022

<a href="https://google.com/"Nice

me — June 12, 2022

NIce

saghar — June 13, 2022

برند اخوان با بیش از نیم قرن سابقه در زمینه تولید لوازم آشپزخانه توانسته بهترین محصولات را با بالاترین کیفیت و مطابق سلیقه افراد وارد بازار کند.

Aarone jose — June 15, 2022

It is the study of the internal structure of the Earth.Vengeance 2022 b.J. Novak black blazer

facebook — June 21, 2022

سازنده فیسبوک کیست با سازنده فیسبوک و زندگی نامه او آشنا شوید

fardin — June 22, 2022

قیمت کلاس آنلاین در ایران

Linda Martin — June 29, 2022

Getting out tobacco smoking is a focal objective in the repulsiveness of cell breakdown in the lungs.Dorothy Red Blazer Jacket

peter shawn — July 7, 2022

Sincerely very satisfied to say,your submit is very exciting to examine. I never stop myself to mention some thing about it. You’re doing a remarkable process. Hold it up Thor Vest

peter shawn — July 7, 2022

Your blog website provided us with useful information to execute with. Each & every recommendation of your website is awesome. Thanks a lot for talking about it. Blade Runner 2049 Jacket

peter shawn — July 7, 2022

Thanks for sharing your information! I bookmark your blog because I found very good information on your America Chavez Jacket

Gujarati Text to Mp3 — July 27, 2022

Gujarati is an Indo-Aryan language belonging to the large Indo-European language family. It is one of the 22 official languages and 14 regional languages of India. The language is simple and relatively easy to learn. As a spoken language, it is concise, simple, and suitable for social and domestic affairs. Convert Gujarati Text to Mp3

Howtospoint — July 27, 2022

Guru is focused on providing people with the knowledge and information they need to answer common how-to questions. How Do I Delete My Childs Instagram Account?

Smith — July 28, 2022

For football lovers everywhere, RleatherJackets offer jaw-droppingly stunning coats. The Washington Commanders, a professional American football club headquartered in Washington, D.C., are the inspiration for this magnificent washington commanders varsity jacket. They are a part of the National Football Conference, which is in the East division of the National Football League (NFC). Only five teams in the NFL have won more than 600 games, including this one. The Boston Braves were established in 1932, and they changed their name to the Commanders in 2022.

Subhash Shastri — August 1, 2022

A must-read post! Good way of describing and pleasure piece of writing. Thanks!

Online Love Solutions

harivanshtours — August 1, 2022

I just wanted to mention I adore it every time visiting your excellent post! Very effective and very correct. Loving your blog. It is refreshing to read this.

Car Rental in Jaipur

Patrika Jones — August 1, 2022

We make it possible for you to pick up whichever screen is best suited for the activity you’re doing and use it with a single cable just like docking your pc at home.

Visit here

www.aka.ms/phonelinkqrc

www.Aka.ms/yourpc

Dainik Astrology — August 2, 2022

I really love your work it’s very beneficial to many people. Your blog approach helps many people like myself. Its content is very easy to understand and helps a lot.

Best Astrologer in Darwin

astrology result — August 2, 2022

Amazing or I can say this is a remarkable article.

How to Solve Inter Caste Love Marriage Problems

Paul Jackson — August 3, 2022

White Americans are substantially less likely to report being "extremely fearful" about pandemics and medical problems impacting themselves or their families, highlighting the stark racial and ethnic inequalities across these four outcomes. People love to wear their favorite outfits like Avengers Infinity War Thor Vest

German Shepherd — August 10, 2022

Should my most memorable pet be a German Shepherd? Might I at any point be the best pet parent? Could I sign up for certain classes or preparing? Assuming a pet person is pondering purchasing or embracing a pet, these are normal inquiries that strike a chord.

Kenzo Madrigal — August 11, 2022

AWESOME POST Stock Fraud Info

Pamila — August 12, 2022

Thanks for sharing this great site Class-Action-Lawsuits

DriverPack Offline — August 12, 2022

No more having to install drivers on your PC or laptop using a CD. All drivers on your laptop will be checked immediately using Download DriverPack Offline ISO for Windows, and the latest updates will be loaded. All drivers for your laptop or computer can be loaded quickly with our DriverPack, regardless of the type of laptop you are using or the version of Windows you are running.

ij.start.canon set up — August 12, 2022

Canon printers are highly reliable and perform excellent printing performance. Their print quality is awesome. Whether you are in search of an inkjet printer, or laser printer, Canon manufactures them both. Canon printers are an excellent choice for professionals wishing to get high-quality printouts and speedy performance. Set up your Canon printer through ij.start.canon set up now.

BRANDO — August 28, 2022

Ensure the work environment you pick is supported and guaranteed and has a decent excess in the business. You can rely upon Viral Growth Media to equip you with the best contender for your necessities. Executive Assistant Placement Florida

SmadAV Latest Version — August 30, 2022

Smadav Rev. 14.8 has the benefit of an extremely tiny installment dimension as well as Smadav makes use of really little internet when energetic on a PC. Smadav, is currently expanding and also has superb capability to combat infections that are dangerous to laptop computers or computer systems. Smadav Antivirus 2022 has the benefit of a really tiny setup dimension as well as Smadav makes use of really little internet when energetic on a PC. As well as you can still mount various other antivirus which can be combined with Smadav to shield your computer.

RLG UK — September 5, 2022

We have an exclusive leather jackets from movies from the collections of popular fashion brand in the UK, which offers reasonable prices and regular discounts.

Patrika Jones — September 5, 2022

aka.ms/myrecoverykey is an application which will allow you to recover your account password if you have forgotten it or lost it. This tool can be used to reset any Disney+ account password.

Visit here Disney Plus Error code 39

Silhouette Cameo 4 — September 7, 2022

Silhouette Cameo 4 is a superb machine with the capability to cut materials of more than a hundred types. Silhouette Cameo uses its sharp moveable blades to cut materials that work precisely. In order to begin the cut job for any materials and create lovely crafts, you can head to the official site, download the Silhouette Cameo Design program setup and install it. Perform the Silhouette Cameo setup process.

Silhouette Cameo 4 — September 7, 2022

Silhouette Cameo 4 is a superb machine with the capability to cut materials of more than a hundred types. Silhouette Cameo uses its sharp moveable blades to cut materials that work precisely. In order to begin the cut job for any materials and create lovely crafts, you can head to the official site, download the Silhouette Cameo Design program setup and install it. Perform the Silhouette Cameo setup process.

emar — September 8, 2022

Much appreciation to you such a ton for sharing this great blog. Amazingly moving and obliging as well. Trust you continue to share a more indispensable extent of your perspectives. I will a great deal of need to check out

http://dominickarwi321.lowescouponn.com/8-go-to-resources-about-website-optimization-northdale

BRAKE — September 8, 2022

I at first thought these were daisies, right now this one is totally amazing. I have no sales that this the truly dumbfounding if not the most incredible in the social affair.

http://trevorjgvt235.yousher.com/10-undeniable-reasons-people-hate-executive-assistant-tampa

Elvis Agnes — September 16, 2022

Our company offers private lessons for PAUD, TK, SD, SMP, SMA, and Alumni. With a built-in and accelerated method, it truly is hoped so it are able to foster an era of people who have good morals... click for more information https://ipa-exed.blogspot.com/2022/04/les-privat-ipa-di-pancoran-terdekat.html

ij.start.canon — October 3, 2022

Canon is a prominent printer brand and has received numerous accolades from people worldwide. Canon printers make inkjet and laser printers. Whether you want to print, copy, or scan documents, you will find canon printers quite perfect for your printing needs. In order to perform the setup procedure for your newly bought Canon printer, you can get to the official site ij.start.canon right now.

John Smith — October 17, 2022

Please visit the Tyler Durden Jacket this is most trendy leather jacket for this winter season and I've buy it from The Jacket Builder in very past I was amazing to wear this jacket the size is perfect, pure leather, quality WOW.

cricut.com/setup — October 20, 2022

Have you ever thought about taking your craft to a new level? If yes, visit cricut.com/setup and sign up to create the best craft project. The website will guide you through the design-making process with step-by-step guidelines. However, you need to understand the different setup aspects of Cricut machines to use them properly. Cricut has introduced several machine versions for cutting, scoring, writing, customizing, sewing, and iron-on transfers. In order to check out which type of project you can create with different Cricut models, go to www.cricut.com setup.

Visit Site - https://set-cricutmaker.com/

mona — October 23, 2022

قابل ذکر است با توجه به این که عموما به متقاضیان ایرانی در ایتالیا بورسیه استانی تعلق می گیرد می توان گفت هزینه تحصیل در ایتالیا در رشته های پزشکی تقریبا رایگان می باشد.

Ulysses Blush — October 24, 2022

Jabodetabek personal teaching products and services having instructors coming to a house. Above 1000 lively tutors are ready to instruct numerous ability in addition to instructions of the to parents ... go to https://bimbel-calistung.netlify.app/les-privat-calistung-depok.html for further

sohail — October 25, 2022

very nise post keep it going

cricut.com/setup — October 26, 2022

If you require an upgraded version of your Cricut software, go to cricut.com/setup Here, you will find the required Cricut tools and gadgets to work with. Now, if you have just bought your Cricut machine and need assistance to set it up properly, follow through with the guide below. Here, we have brought the procedure to set up your machine and Design Space software within steps.

cricut design space — October 26, 2022

If you require an upgraded version of your Cricut software, go to cricut.com/setup Here, you will find the required Cricut tools and gadgets to work with. Now, if you have just bought your Cricut machine and need assistance to set it up properly, follow through with the guide below. Here, we have brought the procedure to set up your machine and Design Space software within steps.

Visit Site - https://cricut-designspaces.com/

silhouette cameo — November 2, 2022

Silhouette Cameo is a great desktop cutting machine that lets you create crafts in an easy way. You can set it up at your home and quickly start the process of making crafts. It cuts materials with precision according to the commands sent by you. It lets a user cut fabric stickers and create custom stickers and tattoos. Moreover, It can cut materials such as leather, vinyl, cardstock, paper, etc. Carry out the Silhouette Cameo setup process to begin using your Silhouette Cameo machine right away.

Visit Site - https://silhouettecameo-pro.com/

https://silhouettecameo-pro.com/cameo-4/

Mariya — November 2, 2022

Thank you for providing this information! I saved your blog because it was very informative. cafe racer jacket

Alex — November 5, 2022

Our ICA Translation Services are affordable and we offer discounts for bulk orders. We also offer a 100% satisfaction guarantee so that you can be sure that you will get the best quality translations.

https://www.icatranslationservices.com/

Yellowstone Clothing — November 8, 2022

your blog is informative because you are using great stuff. The users are also like your blog. also check now Yellowstone Clothing here very big sale active right now

۸ ابزار لازم برای کلاس — November 10, 2022

دیگر ابزار برگزاری کلاس آنلاین میکرفون است؛ چراکه کیفیت صدا، یکی از اصلیترین عواملی است که بر کیفیت یادگیری مخاطبان شما اثر میگذارد.

Justinjesus134 — November 11, 2022

HcaHrAnswers.com login? Here’s the solution! This post covers all questions about HcaHrAnswers login.

Visit My Post: Hca hr answers

Alysia Jims — November 15, 2022

Disease and health issues are always the major issue in old age, especially in the winter season but if you wear warm cloth you can get out of many diseases like cold and fever, celebrity outfits are always my favorite I mostly wear Top Gun Top Gun Lady Gaga Jacket when to parties in cold weather It looks well and comfy on me.

Osepa odisha gov in — November 15, 2022

Odisha state government, in collaboration with the Education department, has implemented exclusive platforms to cater for education programs. The OSEPA Odisha is an initiative by the government incorporating schools, teachers, and students’ details. Osepa odisha gov in The system helps cover information about Odisha state schools under a single portal. Students can avail school syllabus, courses, subjects, exam details, and more.

inlays and onlays in turkey — November 15, 2022

Your content was really great. We follow your website with interest. We wish you luck.

inlays and onlays in turkey — November 15, 2022

Your content was really great. We follow your website with interest.

ishagarg — November 21, 2022

Hi companions ! If you have any desire to get the best assistance, then you can agree with it from our position, which our side gives the best help. Gives different sorts of administration.

Lukeasher345 — November 22, 2022

They are well-known for their coffee and breakfast items like doughnuts and muffins.

Visit My Post: telltimscaanada

Christy Peetoom — December 1, 2022

Jabodetabek private tutoring services with teachers traveling to the house. Above a huge selection of active tutors will be ready teach various skills and lessons for youngsters to adults ... click https://privat-sbmptn.vercel.app/les-privat-sbmptn-pejaten.html for further

Microsoft365.com/setup — December 3, 2022

Need a Microsoft Office Setup Guide Online? Go to microsoft365.com/setup you will receive Microsoft 365 subscription plans with Office apps to help you get things done. A Microsoft 365 account gives you access to the latest versions of Microsoft Office products. Before activating Microsoft 365, see the Office regulations below.

Visit Site - https://micro365setup.com/

Emmanuel Conkle — December 7, 2022

Jabodetabek private tutoring services with teachers going to the house. Above hundreds of active tutors will be ready teach various skills and lessons for children to adults ... click https://privat-matematika.vercel.app/les-privat-matematika-palmerah.html for more details

jackmaa21 — December 8, 2022

You'll need to Amex Login after you download and launch the app., the same way you would on a computer, enter your login and password. Amex Login

ij.start.canon — December 14, 2022

For multifunctional printers, you can easily get the setup directions at ij.start.canon If your query is about how to connect the Canon printer to Wi-Fi, this guide is for you. Get the instructions whether you require help with wireless setup or connect your printer model to Wi-Fi. Also, you explore ij.start.canon to get the driver for your particular Canon printer series.

https://ijstart.printerstartsetup.com/

niti — December 22, 2022

ثبت نام علامه طباطبایی چه تاریخی شروع میشه؟

jack maa — December 27, 2022

Once the account has been Coinbase Sign in. created at this exchange, you will then be able to the Blockchain.com login crypto funds with the help of The steps that will let you land you back into your account are as follows

Kingston321 — December 31, 2022

Customers of Marks & Spencer have good news: you can win £250 or €300 in cash. Share your Marks & Spencer Customer Survey

Visit My Post: www.makeyourmands.co.uk

mariya jones — January 7, 2023

MetaMask Wallet is a cryptocurrency wallet available as a browser extension for Chrome, Firefox, Opera and Brave. Thе wallet serves as a connection between your browser and the Ethereum blockchain.

Crypto.com Log in: The best place to buy Bitcoin, Ethereum, and 250+ altcoins *Terms and Conditions apply. Join 70M+ users buying and selling 250+ cryptocurrencies at true cost Spend with the Crypto.com Visa Card

Andrew Brian — January 17, 2023

Sincerely very satisfied to say, your submit is very exciting to examine. I never stop myself to mention some thing about it. You’re doing a remarkable process. The Best Jacket gives you best opportunity to avail up to 60% OFF on Fight Club Tyler Durden Jacket. Don't miss the sale.

Suede Leather Jacket for Men's

jack maa — January 25, 2023

you will then be able to function the activities relating to the crypto funds with the help of a Coinbase sign in. In order to begin the MetaMask journey, there is no signup process required. All you need Here is the guidance to create a Metamask Sign in

silhouette cameo 4 — January 25, 2023

Silhouette Cameo 4 is an ultimate DIY electronic cutting machine that lets you cut different materials in no time and provides endless possibilities to create projects. People are using this amazing machine all over the world. You can, too, take the benefit by installing and setting up your personalized Silhouette Cameo via its official website.

Silhouette Cameo 4

Gateway International — February 22, 2023

Gateway International is an organization with a vision of making every student study abroad for the last 15 years and shaping careers for all those deserving and enthusiastic aspirants of all ages who want to transform themselves into professionals in their fields.

Academic Assignments — March 14, 2023

Great blog. Absolutely well written.

It would be so great if you check out the Swot Analysis Assignment HelpIt is a structured method of planning od any organization, project, etc

Our team of specialists performs 100% analysis at a time for scrumptious quality.

Your data is safe from any unethical act.

original content with 0% plagiarism

jonny — March 15, 2023

چگونه جلسات آنلاین را مدیریت کنیم؟

silhouette cameo 4 — March 27, 2023

Silhouette Cameo simplifies that whole craft-making process. In today's day and age, a crafter doesn't need to get his hands dirty. The entire craft-making process can be done within a few minutes with a simple button push. All Silhouette machine uses the powerful Silhouette Studio software. You can use it to import your fonts and images or create a design from scratch.

Silhouette Setup — March 27, 2023

The Silhouette Cameo 4 is a cutting machine that works with your computer or mobile device (Windows, PC, Android, or Mac). It’s about the same size as a home printer. It also includes software that enables you to make anything. These designs can be cut out afterward on vinyl, fabric, paper, or heat transfer material. The machine is incredibly adaptable, allowing it to produce complicated projects of any scale, from little to enormous. The Cameo and the Portrait are two separate cutting machines offered by Silhouette. Silhouette Cameo software, on the other hand, is where the real magic happens. Upgrade the software to Silhouette Studio Design Edition to use the Silhouette Cameo 4 machine with a wider range of designs.

Silhouette Cameo 4

Silhouette Cameo

kahoot winner — April 1, 2023

Ser el ganador de Kahoot no es solo cuestión de responder preguntas correctamente. Requiere preparación, estrategia, conocimiento de las reglas del juego y la capacidad kahoot winner de adaptarse a diferentes modos de juego. Si sigues estos consejos y te diviertes mientras aprendes, ¡seguramente te convertirás en un ganador de Kahoot en poco tiempo!

gmail posteingang — April 3, 2023

Sie können viele Einstellungen in Gmail anpassen, um Ihre Erfahrung zu verbessern gmail posteingang einschließlich der Einstellungen für Benachrichtigungen, Labels und vielem mehr.

matka final ank — April 11, 2023

Hello, I found your website via Google while searching for related topics, your website came up, looks great. I have bookmarked it in my google bookmarks. Spanduk Jakarta Timur I can’t leave your site before saying that I really enjoy the standard information you provide to your visitors? Will be back often to check for new posts.

devgoyal — April 13, 2023

Insgesamt ist Burning Series eine beliebte Plattform für das Streamen von Serien. Es bietet eine große Auswahl an Inhalten und ist für viele Nutzer attraktiv, da es kostenlos ist. Allerdings sollten https://burningseries.pro/ Nutzer sich der möglichen Risiken und rechtlichen Konsequenzen bewusst sein, bevor sie die Plattform nutzen. Es ist immer empfehlenswert, legale Streaming-Dienste in Betracht zu ziehen, um sicherzustellen, dass man Serien auf sichere und legale Weise genießen kann.

mahii52 — May 16, 2023

Tin Mail è un servizio di posta elettronica che si contraddistingue per la sua attenzione alla sicurezza e alla privacy dei suoi utenti. Utilizza tin.it mail una crittografia end-to-end per proteggere i tuoi messaggi, garantendo che solo il mittente e il destinatario possano leggerli.

Dubai Safaris — May 17, 2023

It is great to see that some people still put in an effort into managing their websites. I'll be sure to check back again real soon. its really amazing

posteingang gmail öffnen — May 17, 2023

Sicherheit ist ein weiterer entscheidender Aspekt von

posteingang gmail öffnen Die Plattform implementiert fortschrittliche Sicherheitsmaßnahmen, um die Privatsphäre der Benutzer und ihre persönlichen Daten zu schützen. Dazu gehört eine Ende-zu-Ende-Verschlüsselung für Kommunikation sowie Spam-Filter, die das Postfach sauber und frei von unerwünschten Nachrichten halten.

mail3 — May 17, 2023

mail tim offre anche una capacità di archiviazione generosa, consentendo agli utenti di conservare un'ampia quantità di e-mail senza preoccuparsi di spazio insufficiente. Inoltre, la funzione di ricerca avanzata facilita la ricerca di messaggi specifici all'interno dell'account.

white monde — June 7, 2023

At white monde interior fitout company in Dubai, We believe that it's the little details that truly make a difference in the overall design.

wordlecat — June 12, 2023

wordlecat es un juego que requiere que los jugadores utilicen habilidades de pensamiento analítico para deducir la ubicación correcta de las letras.

Butler — June 14, 2023

Great article! Your insights on this are thought-provoking and well-articulated. We also provide valuable resources on rebar estimating services . Keep up the excellent work!

bigtorrent.eu — June 20, 2023

A BigTorrent nem csak egy egyszerű letöltési platform, hanem egy közösség is, ahol az emberek megoszthatják az érdekes és izgalmas tartalmakat egymással. Ez a közösségi jelleg teszi igazán vonzóvá az oldalt. A felhasználók véleményeket oszthatnak meg, beszélgethetnek a kedvenc filmjeikről, zenékről vagy szoftverekről, és még új barátokra is szert tehetnek, akik hasonló érdeklődési körrel rendelkeznek.

bigtorrent.eu — June 20, 2023

A bigtorrent.eu nem csak egy egyszerű letöltési platform, hanem egy közösség is, ahol az emberek megoszthatják az érdekes és izgalmas tartalmakat egymással. Ez a közösségi jelleg teszi igazán vonzóvá az oldalt. A felhasználók véleményeket oszthatnak meg, beszélgethetnek a kedvenc filmjeikről, zenékről vagy szoftverekről, és még új barátokra is szert tehetnek, akik hasonló érdeklődési körrel rendelkeznek.

heardle 80s — June 23, 2023

Si adivinas correctamente, las letras de la canción se revelarán en las casillas correspondientes y podrás pasar a la siguiente canción. Si te equivocas, deberás intentar nuevamente con diferentes letras hasta agotar tus seis intentos.

heardle 80s — June 23, 2023

heardle 80s Si adivinas correctamente, las letras de la canción se revelarán en las casillas correspondientes y podrás pasar a la siguiente canción. Si te equivocas, deberás intentar nuevamente con diferentes letras hasta agotar tus seis intentos.

gmail posta — July 4, 2023

Gli utenti possono gmail posta inviare email fino a 25 megabyte di dimensione. Gmail ha un'interfaccia utente focalizzata sulla ricerca e una visualizzazione delle chat che ricorda un forum. Con circa 1,5 miliardi di utenti attivi in tutto il mondo, Google è attualmente il principale provider di servizi di posta elettronica a livello internazionale.

2023 — July 14, 2023

Las enormes colecciones en 2023 esta plataforma nunca aburren fácilmente a los usuarios, ya que están tan conectados con ella que se ha convertido en una necesidad diaria para la comunidad local.

silhouette.com/software — July 28, 2023

Silhouette Cameo is the choice of professional crafters who are in the business of making decorative crafts, stickers, and tattoos. If you are in search of an excellent cutting and crafting machine, the Silhouette Cameo is the only cutting machine that can put your search to an end. The Silhouette Cameo machine can be set up quickly with the procedure described below and used to make the designs on materials.

Robert Gandell — August 2, 2023

Native Assignment Help offers specialized Oracle Assignment Help services designed to cater to student's academic needs in the field of Oracle database management systems. Our team of Oracle experts possesses extensive knowledge and experience, ensuring that students receive well-crafted solutions to their Oracle assignments. From basic SQL queries to complex database designs, our experts provide comprehensive assistance to help students excel in their Oracle-related projects and secure top grades.

viperplay — August 7, 2023

La aplicación cuenta con viper play barcelona una interfaz intuitiva y fácil de usar, lo que te permitirá navegar sin complicaciones y acceder a toda la información de manera rápida y sencilla.

seriesflix — August 8, 2023

seriesflix gratis se ha ganado su lugar como un destino popular para el entretenimiento en streaming por una buena razón. Su variado contenido, interfaz fácil de usar y experiencia personalizada la convierten en una opción atractiva para los amantes de las series y el cine.

ios scarlet — August 8, 2023

ios scarlet também coloca grande ênfase na segurança de dados e privacidade do usuário. Através do uso de criptografia avançada e autenticação biométrica, o sistema operacional procura garantir que as informações pessoais permaneçam protegidas contra ameaças cibernéticas. Além disso, o ScarletiOS permite que os usuários controlem quais dados desejam compartilhar com aplicativos e serviços de terceiros.

pelisflix 2 — August 9, 2023

En la era digital actual pelisflix 2 en línea se ha convertido en una parte integral de nuestras vidas. Las plataformas de streaming han revolucionado la forma en que consumimos contenido audiovisual, y una de las opciones más destacadas en este ámbito es Pelisflix.

اخبار فناوری — August 12, 2023

Thank you for your good article

assignment assistance — August 23, 2023

We offer professional assignment assistance services to help students excel academically. Our team of skilled experts is experienced in various subjects and can provide expert guidance, proofreading, and editing services.

آموزش تعمیرات موبایل — August 24, 2023

توبیکس برگزار کننده ی بهترین و مجهزترین دوره آموزش تعمیرات موبایل در کشور

best leather jacket — August 28, 2023

We offer professional Leather Jacket services to help students excel academically. Our team of skilled experts is experienced in various subjects and can provide expert guidance, proofreading, and editing services.

Lily Smith — September 30, 2023

Great you have given valueable insights on social inequality and medical fears.

If you are facing problems with your assignment writing, Get Online Assignment Help from Instant Assignment Help.

Baker Forest — October 3, 2023

Visit www.disneyplus.com/begin on your machine or stream devices to discover more about the Disney Plus activation process. By signing up online on Disneyplus.com/begin you can watch the limitless variety of movies, sport event and TV series from anywhere at any time. Access to all of the platform's content is unlimited with a monthly subscription plan. For even more entertainment value, you may combine Disney+ with Hulu and ESPN+ using the bundle choices it offers.

wescherlem — October 4, 2023

If you're feeling anxious about your upcoming examinations, we'd like to introduce you to our esteemed take my exam online service. Our experienced team is dedicated to helping you excel in your online exams. Entrust us with your exam preparations to ensure you're well-rested. We are committed to delivering exceptional results; now is your opportunity to shine.

best nightclubs in Udaipur — October 6, 2023

Exploring the best nightclubs in Udaipur is a fantastic way to experience the city's lively nightlife and immerse yourself in its vibrant music and dance culture.

www.disneyplus.com/begin code — November 3, 2023

The user-friendly interface of disneyplus.com/begin makes it a joy to navigate and discover new content.

www.disneyplus.com/Begin — November 4, 2023

The documentaries on disneyplus.com/begin offer a fascinating behind-the-scenes look at the magic that goes into creating Disney's iconic stories.

James Parker — November 4, 2023

Assignment helper are instrumental in supporting students' educational success. They offer guidance and aid in tackling coursework, research, and homework assignments. By providing valuable insights, these helpers empower students to grasp challenging subjects and improve their academic performance. Their expertise is a valuable resource for those seeking academic excellence.

best nightclubs in Udaipur — November 15, 2023

Exploring the best nightclubs in Udaipur

Pet Lada — November 16, 2023

There is something so soothing about the sound of a cat's purr or the wag of a dog's tail. It's a language of comfort and contentment.

leatherback bearded dragon

study abroad — November 16, 2023

study in malaysia can be an exciting and enriching experience. Malaysia offers a unique blend of cultural diversity, natural beauty, and academic excellence.

Disneyplus.com/begin — November 21, 2023

Disneyplus.com Login/Begin

We provide you information about how to activate your tv channels Disneyplus.com/Begin

disneyplus.com login/begin tv — December 11, 2023

Watching disneyplus.com login/begin tv is not just a viewing experience; it's a journey through time, space, and the boundless imagination of the House of Mouse.

Disneyplus.com login/Begin — December 15, 2023

www.disneyplus.com login/begin 8 digit code tv turns ordinary evenings into extraordinary adventures, making every movie night a celebration of storytelling brilliance.

disneyplus.com/start — December 15, 2023

The variety on disneyplus.com/start is impressive. From animated classics to the latest Marvel and Star Wars releases, there's something for everyone in the family.

arsanet — December 19, 2023

یکی از بهترین سایت های خرید سنگ ساختمانی از محمود آباد اصفهان

https://isfahanstone.com/

سنگ محمود آباد — January 2, 2024

خرید سنگ ساختمانی در سایت بازاراستون

amidh — January 2, 2024

برای آشنایی بیشتر با پروفیل کناف کلیک کنید

خیام ثبت — January 2, 2024

ثبت شرکت با مسئولیت محدود در اصفهان

نرده سنگی — January 2, 2024

https://azarinstone.com/

Abroadstudying — January 11, 2024

Studying abroad in Cyprus can be an exciting opportunity. Cyprus is known for its beautiful Mediterranean climate, rich history, and vibrant culture.

It's crucial to research specific universities, programs, and the application process thoroughly.

https://edysor.in/other-speaking-countries/study-in-cyprus

classdoerr — January 29, 2024

Our team offers top-notch service 24/7, providing the best outcomes for every student. Challenges are no problem for you, as all users of Classdoer will reap the rewards of take my math class for me.

classdoerr — January 29, 2024

In addition to providing online tuition, I am also available to assist with assignments and projects. My skills and knowledge make me capable of providing appropriate advice. If you need any help don't hesitate to get in touch with me, Pay someone to do my online class! Availability and reliability are my top priorities. If you need help simplifying your life and saving time, I am confident I can help you. Contact me now to get started!

amiestanleys — February 5, 2024

There are many diet pills on the market that claim to help people kick start the fitspresso weight loss process. Another oil that is a very healthy oil that can really help you burn your fat faster is coconut oil. One main reason of getting natural supplements is that they are not prone to causing side effects. Until then, they still carry a high risk of side effects. https://fitspresso.fitmdblog.com/

Exchange Savvy — February 13, 2024

While Microsoft Exchange and Microsoft 365 are distinct in their primary functions, they complement each other seamlessly to create a powerful communication and productivity ecosystem. https://www.exchangesavvy.com/

More Tranz — February 19, 2024

DTF transfer sheets offer several advantages, including vibrant color reproduction, high-resolution printing capabilities, and the ability to transfer intricate designs onto various materials. They are commonly used in the production of custom apparel, promotional items, and personalized goods.

Nisa Fitri — February 27, 2024

Dive into the dynamic realm of whatsapp mod APKs with our comprehensive article that explores the enhanced messaging experience these modified versions offer.

jamesh leo — March 12, 2024

Assignment Help Pro stands out as a beacon of excellence in Malaysia's academic landscape, offering unparalleled assignment writing services. With a dedicated team of seasoned writers, they prioritize quality, originality, and punctuality in every project they undertake. Their commitment to thorough research ensures that each thesis is meticulously crafted to meet academic standards and exceed expectations. Furthermore, their track record of timely delivery underscores their reliability and dedication to customer satisfaction. As a result, Assignment Help Pro rightfully claims the title of the best assignment help in Malaysia . For students seeking academic excellence and peace of mind, entrusting their assignments to Assignment Help Pro guarantees not only top-notch quality but also the assurance of achieving their academic goals.

Skin Aholics — March 19, 2024

It's important to note that while blue light therapy is generally safe and well-tolerated, some individuals may experience mild side effects such as temporary redness or dryness of the face masks skin. It's essential to consult with a healthcare professional or dermatologist before starting blue light therapy to determine if it's suitable for your specific needs and to receive personalized treatment recommendations.

nicomrboen — March 23, 2024

Thanks for the Information

latin cary — April 2, 2024

Writing strong Good Hooks For Essay is important to successfully capture readers' attention. The goal is to leave a lasting impression, whether that's achieved by starting with a provocative question or adding memorable images, stories, statistics, or quotes. Make sure your hook does a good job of attracting the reader and introducing the key points of your work. An engaging hook encourages readers to keep reading by engaging with them and piquing their curiosity. Therefore, focus on creating hooks that will enthrall and captivate readers so that they will read your essay till the end.

CTTIP Danışmanlık — April 4, 2024

Çinden ithalat yapan türk firmaları arasında uzman ekibe sahip CTTIP ile ihracat ve çinde yatırım yapma konularında hizmet ve danışmanlık alın.

Fauxjacket — April 7, 2024

The best faux leather jackets are the ones that make you happy. And our effort is to provide you with petite faux leather jacket. So visit our site now.

everex — April 15, 2024

طراحی سایت در قزوین

سئو در قزوین

Claire Miller — April 20, 2024

Your tips for scoring high in Holmes exams have completely transformed my approach to studying! I've always struggled with standardized tests, but your blog post has given me hope and confidence like never before. What resonates with me most is the emphasis on critical thinking skills and effective time management – two areas where I've often fallen short. Your practical advice is like a roadmap guiding me through the complexities of Holmes exams with clarity and precision. I've already started implementing your strategies, and I can feel a newfound sense of purpose and determination. Read about Top 10 Tips to Score High in Holmes.