If you walked through a city without looking up at any billboards, could advertisers yell at you? Could the owner of an iconic building shame you for “stealing” a beautiful view while weaseling them out of their livelihood? It sounds absurd, and you might remember a viral quote from Banksy (riffing on original writing from Sean Tejaratchi), tearing the idea apart.

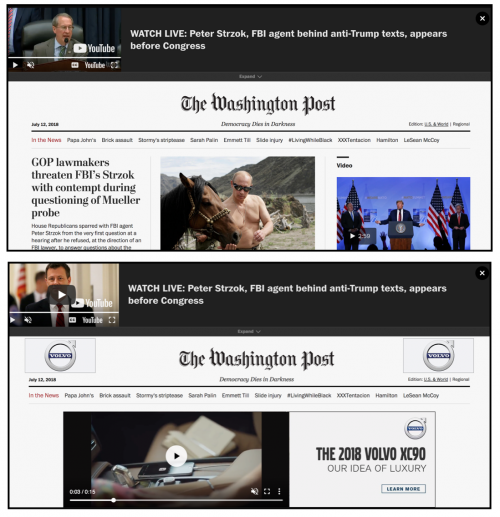

But what about digital advertising? The internet looks very different if you are using software to block advertisements. Use it for a long time you’ll forget how much junk a user has to slog through to read or watch anything.

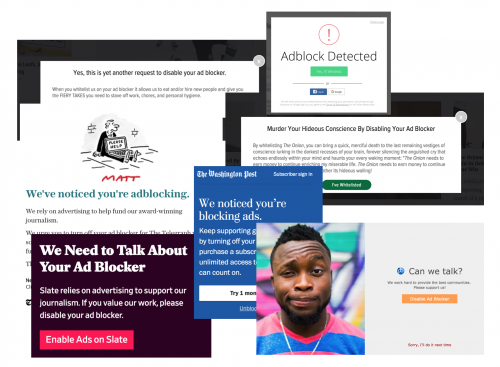

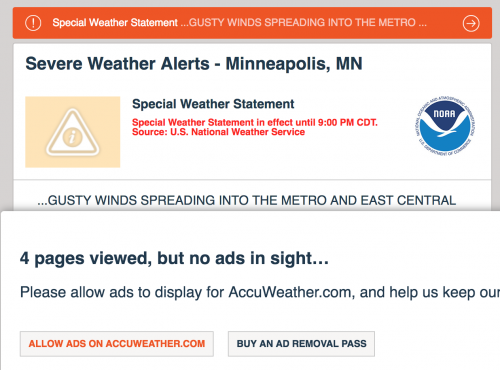

Of course, blocking ads cuts into the main source of support for online publications. Lately, many have taken up a new approach to discourage their users from blocking ads: good old fashioned shame and guilt.

We can have an important conversation about the ethics of paying for content online, but what strikes me the most about these pop-ups are some core sociological questions about the shaming tactic: why here, and why now?

For a long time, social scientists have seen a “digital divide” in how unequal access to the internet reinforces social inequality. Research also shows that the digital divide isn’t just about access; people learn to use the internet in different ways from these early access experiences. From the design side, sociologists Jenny Davis and James Chouinard have also written about affordance theory: the way technology requests, demands, allows, encourages, discourages, and refuses different kinds of behavior from users.

For some, the internet is about abundance and agency. Take as much time as you need to figure out your problems, and, if things don’t work out, bend the world to your will! Grab open source software or write a script to automate the boring stuff! Open your app of choice to hail a ride if the bus is delayed or the taxis are busy! For others, these choices aren’t as readily apparent. If you had to trek to the library and sign up for time-limited computer access, the internet can seem a lot less helpful and a lot less free, at least at first glance.

These ideas help us understand the biggest problem for ad-block shaming: “soft” barriers, delays, and emotional appeals are trying to change the behavior of people who already have the upper hand from learning to seek out and use blocking software to make the internet work better for them. David Banks’ writing on this over at Cyborgology in 2015 shows the power struggle at work:

The ad blocker should not be seen as a selfish technology. It is a socialist cudgel—something that forces otherwise lazy capitalists to find new and inventive ways to make their creations sustainable. Ad blockers are one of the few tools users have to fight against the need to monetize fast and big because it troubles the predictability of readily traceable attention.

Now, emotional appeals like guilt and shame are the next step after stronger power plays like rigid paywalls largely failed for publishing companies. The challenge is that guilt and shame require a larger sense of community obligation for people to feel their effects, and I am not sure a pop-up is ever going to be anything other than an obstacle to get around.

It’s not that online advertising is inherently good or bad, and the problem of paying artists and writers in the digital age is a serious concern. But in addition to these considerations, looking directly at the way web design tries to shape our online interactions can better prepare us to see how the rules of the social world can be challenged and changed.

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, or on BlueSky.

Comments 31

NM — July 12, 2018

I turned off my adblocker the other day and it still wouldn't let me view the site. They wanted me to turn off my Firefox tracking protection too. That's a step too far.

a — July 12, 2018

Yep, NM, most of the time I'm requested to turn of Adblock Plus, I do and the site still won't work. Then I just leave without seeing anything!

Lanth — July 12, 2018

The real failure of adblock shaming is that, on the occasions where I've complied, I then rediscover why I use adblock -- and turn it back on immediately. Internet ads have only gotten worse and worse over the decades, to the point where they're no longer selling products, they're selling fear, self-loathing, and compulsive behavior.

Eddie — July 14, 2018

https://jspenguin2017.github.io/uBlockProtector/ bypass any lame anti ad block crap

Ernesto Terribile — July 15, 2018

If it was only for sustain sites ... we can discuss.

But when I have metered connection (like with mobiles) and I'm forced to download MB of crap for just some kB of real content, I am not happy with it.

Also, Ads slow down the time to open pages. Time that the user is wasting for nothing.

Just to point out, the newspaper USAToday for respecting EU GDPR made a version for Europe without all this crap. Result is that the site loads in less than a second and it requires just a few kB of data transferred.

Ads system is sick to the bone and, in my humble opinion, requires a complete redesign.

Fiona — July 15, 2018

For some of us, adblockers make the internet accessible. I am on the spectrum, and I simply cannot cope with the additional visual load of adverts all over the page, especially the flashing gifs or autoplay videos. Many sites are simply inaccessible to me because of this. I also don't watch television for the same reason, and have given up on pubs, cafes and restaurants that shove advertising screens in your line of site. Living rural I rarely use public transport, but on the rare occasion I do I now have to cope with the onslaught of screen advertising as well as everything else.

Advertising is destroying the ability of many of us to simply go quietly about our lives.

Robson — July 15, 2018

I am all for letting content owners finance themselves. However, here is the thing: I'm not for sale! I won't allow anyone to track me or to gather information that is private.

Here is a deal: if you want to use advertising, it's fine, as long as you don't track me. Display adverts that relate to the page content ONLY and that's fine with me. So, no Google ads for me.

dan — July 15, 2018

It's not advertising anymore. It's turned into behavior modification.

Simba — July 19, 2018

we use shame to discourage bad behavior, not good behavior. This is an in your face example of how you have allowed your society to set itself up for self-destruction by neglecting foundational principals.

The American Dream is not to cheat people until they give you all their money, and all of those who disagree should go straight to hell, without passing go.

rez — July 25, 2018

Social engineering... shaming... language policing... the Left is turning into a horror show. Amazing to have gone the full nine yards since the 60's big dream to end up in this cultural fascist ghetto presided over by liberal gestapo. No wonder Trump keeps holding at around 45% whatever he does.

emma wilcock — August 2, 2018

i have been blocking adverts on TV by my remote control mute button for well over a decade now. i despise Advertising and anything i can do to cut down on this brain assault is fine with me. The type of advertising that really disturbs me are those flashing lights around the a football pitch, they seem to be programmed to follow the action. One particular one thats penetrated my defences is a Dachshund that run along the edge of the pitch like speedy left winger,its horrible. The flashing adverts are so intrusive that i have the nagging suspicion that they could trigger a reaction with people with epilepsy or who are on that autistic spectrum.

Lucky Joestar — August 27, 2018

These Adblock shamers seem to forget that they don’t own our computers. We own them, so we have every right to block out all that malware they’re trying to put on our computers. They act like they’re entitled to put whatever garbage they please on our personal property. If their revenue from advertising is drying up, they need a new way to get revenue, such as through donations. Covering up the content with a popup whining about how we’re a bunch of Blue Meanies keeping them from getting paid isn’t going to earn our sympathy.

Liam — March 31, 2021

Three years later and this is still an issue. I have an adblocker because lots of these ads are scam ads that I am tired of seeing.

Albert G. Wiggins — November 25, 2021

After developing a distinctive kind of the innovation, you can deal with each sort of the errand. Innovation is stating that the assignment which you think about is unimaginable, presently it is conceivable and also they can visit essay help site for quality work. I comprehend that the DVD can't show the picture yet it is currently conceivable.

paper assistance — January 26, 2022

Combine Things That Don’t Go Together

This creates curiosity. Add in a buildup before you reveal the secret and you create anticipation. For example, I once wrote an article about a Thomas Jefferson persuasion tactic in the Declaration of Independence.

pianomongoose — April 6, 2022

google

bdjscresult2018.com — May 19, 2023

According to the Ministry of Primary and Mass Education (MOPME), the Bangladesh Education Board DPE successfully conducted the class eighth grade terminal examination tests for all eligible JSC/JDC students for the academic year from November 1st to 15th at all centres in division-wise. There are 9 education bdjscresult2018.com boards working under the Primary and Maas education ministry, and information indicates that 18,778 school students from all division education boards in the nation are participating in the exam. Students who pass the JSC/JDC exams will receive stipends from the Bangladeshi government, allowing them to easily continue their higher classes.

samibaceri — June 19, 2023

How sites don't like that no one wants to donate, and no one wants to watch ads either. There's so much quality software, out-of-the-box solutions, and online tools out there now, and I don't understand why so many business owners still have some problems. For example, I use a lot of Pandadoc products, and the templates I recently found on this site have saved me from having to create documents from scratch every time.

betjee — November 30, 2023

Adblockers are really an option for users. To shame though is a different level. We cannot be purist in all forms. It is part of the industry. It always fair to hear both sides of the story. I guess that's what free market is all about.

conradmurray — November 30, 2023

People can always use adblockers. It is their option. I agree with https://betjee.com/ it is best to weigh opinions if you have two sides, otherwise, it is a monopoly of ideas.

payandeh — November 30, 2023

ah you mean betjee

Shirley Aguirre — March 26, 2025

Interesting article on adblock shaming! It's a complex issue. Users are often bombarded with intrusive ads, pushing them to block. Perhaps a focus on less disruptive formats, like flappy bird's simple monetization, could be a solution? Instead of invasive pop-ups, offer optional,less annoying interactions.

emma nuelrippin — March 26, 2025

Exploring ad blocking reveals a fascinating power dynamic. Users now adept at shaping their online experience resemble players mastering Infinite Craft, building their ideal internet. Guilt trips and shame tactics feel like clumsy attempts to restrict that freedom, especially after paywalls failed. It's not about demonizing ads, but understanding how web design influences our choices and empowers us to redefine the internet's rules. Sustainable models are the key.

alvismarvin — March 27, 2025

Imagine navigating the digital jungle without ad blockers. It's like managing a chaotic Monkey Mart, bombarded with distractions at every turn. Suddenly, the serene experience of browsing vanishes, replaced by a barrage of unwanted noise. Remember, a clean online space is as essential as a well-stocked Monkey Mart for happy customers.

Snow Rider 3D — March 28, 2025

Digital advertising plays a crucial role in sustaining online platforms, but the rise of ad-blocking has sparked debates about its impact. While some users prefer an ad-free experience, websites must balance user satisfaction and revenue generation. This raises important questions about ethics, like the "adblock shaming" trend. A relatable escape from these complexities is diving into games like Snow Rider 3d, offering pure fun and a break from digital dilemmas.

sophia — April 5, 2025

The growing use of guilt and shame tactics to discourage ad-blocking highlights a complex tension between monetizing online content and respecting user autonomy, raising important questions Stimulation Clicker about digital ethics, power dynamics, and the evolving design of online spaces.

kevin — April 25, 2025

What's the success rate of the adblock shaming? Maybe an indepth analysis will pinpoint the why's. That's the reason I take my mind off from the arguments. I don't want to be stressed. Right now, I'm looking for biggest food trade show for a research.

Thomas Franks — May 12, 2025

Among Us Online is a clear example of how a graphically simple game can still create global waves. Thanks to the social element and the ability to create situations with players, the game is always new every time you log in. No one can predict what will happen. That is why Among Us has become a phenomenon in the online gaming community.

Patrick — May 14, 2025

I use Incredibox not because I’m stingy, but because I value my time and my sanity. There are too many annoying, scammy, malicious ads – I can’t handle them all. If sites really want me to contribute, they should provide valuable content and give me the option to donate voluntarily. The ‘compassion appeal’ of pop-ups just makes me feel more annoyed and cold.

David — June 27, 2025

Ragdoll hit is an epic ragdoll action game featuring intense battles and unique ragdoll physics

Milton — July 23, 2025

You’ve clearly put a lot of effort into creating helpful content. Thank you for this amazing post—it’s made a big impact. circ02