“Manspreading” is a relatively new term. According to Google Trends (below), the concept wasn’t really used before the end of 2014. But the idea it’s describing is not new at all. The notion that men occupy more space than women is one small piece of what Raewyn Connell refers to as the patriarchal dividend–the collection of accumulated advantages men collectively receive in androcentric patriarchal societies (e.g., wages, respect, authority, safety). Our bodies are differently disciplined to the systems of inequality in our societies depending upon our status within social hierarchies. And one seemingly small form of privilege from which many men benefit is the idea that men require (and are allowed) more space.

It’s not uncommon to see advertisements on all manner of public transportation today condemning the practice of occupying “too much” space while other around you “keep to themselves.” PSA’s like these are aimed at a very specific offender: some guy who’s sitting in a seat with his legs spread wide enough in a kind of V-shaped slump such that he is effectively occupying the seats around him as well.

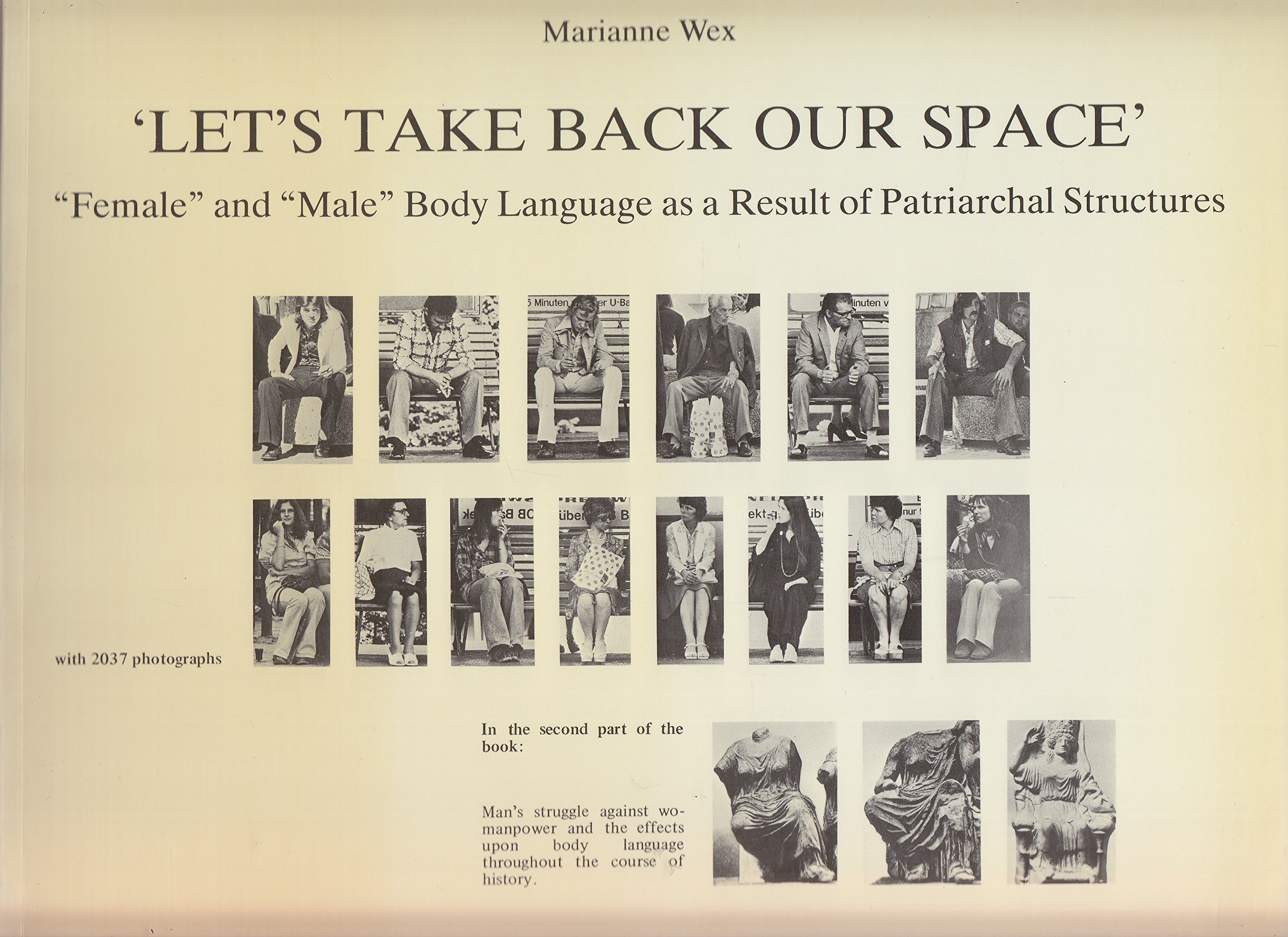

I recently discovered what has got to be one of the most exhaustive treatments of the practice ever produced. It’s not the work of a sociologist; it’s the work of a German feminist photographer, Marianne Wex. In Wex’s treatment of the topic, Let’s Take Back Our Space: Female and Male Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures (1984, translated from the German edition, published in 1979), she examines just shy of 5,000 photographs of men and women exhibiting body language that results from and plays a role in reproducing unequal gender relations.

The collection is organized by an laudable number of features of the various bodily positions. Interestingly, it was published in precisely the same year that Erving Goffman undertook a similar sociological study of what he referred to as “gender display” in his book, Gender Advertisements–though Goffman’s analysis utilized advertisements as the data under consideration.

Like Goffman, Wex examined the various details that made up bodily postures that seem to exude gender, addressing the ways our bodies are disciplined by society. Wex paired images according to the position of feet and legs, whether the body was situated to put weight on one or two legs, hand and arm positions, and much much more. And through this project, Wex also developed an astonishing vocabulary for body positions that she situates as the embodied manifestations of patriarchal social structures. The whole book organizes this incredible collection of (primarily) photographs she took between 1972 and 1977 by theme. On every page, men are depicted above women (as the above image illustrates)–a fact Wex saw as symbolizing the patriarchal structure of the society she sought to catalog so scrupulously. She even went so far as to examine bodily depiction throughout history as depicted in art to address the ways the patterns she discovered can be understood over time.

If you’re interested, you can watch the Youtube video of the entire book.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ScoOF2GDFrM

Tristan Bridges, PhD is a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is the co-editor of Exploring Masculinities: Identity, Inequality, Inequality, and Change with C.J. Pascoe and studies gender and sexual identity and inequality. You can follow him on Twitter here. Tristan also blogs regularly at Inequality by (Interior) Design.