Prisoners who can maintain ties to people on the outside tend to do better — both while they’re incarcerated and after they’re released. A new Crime and Delinquency article by Joshua Cochran, Daniel Mears, and William Bales, however, shows relatively low rates of visitation.

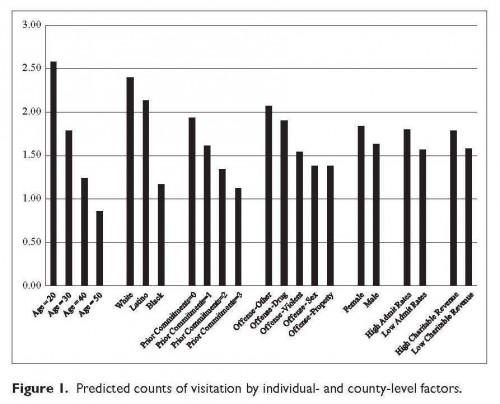

The study was based on a cohort of prisoners admitted into and released from Florida prisons from November 2000 to April 2002. On average, inmates only received 2.1 visits over the course of their entire incarceration period. Who got visitors? As the figure below shows, prisoners who are younger, white or Latino, and had been incarcerated less frequently tend to have more visits. Community factors also shaped visitation patterns: prisoners who come from high incarceration areas or communities with greater charitable activity also received more visits.

There are some pretty big barriers to improving visitation rates, including: (1) distance (most inmates are housed more than 100 miles from home); (2) lack of transportation; (3) costs associated with missed work; and, (4) child care. While these are difficult obstacles to overcome, the authors conclude that corrections systems can take steps to reduce these barriers, such as housing inmates closer to their homes, making facilities and visiting hours more child-friendly, and reaching out to prisoners’ families regarding the importance of visitation, both before and during incarceration.

Cross-posted at Public Criminology.

Chris Uggen is a professor of sociology at the University of Minnesota and the author of Locked Out: Felon Disenfranchisement and American Democracy, with Jeff Manza. You can follow him at his blog and on twitter.

Comments 9

Christine — September 13, 2014

I'd be interested to see these figures adjusted for length of sentence - I think the interpretation would change if we saw an average of 2 given a sentence of 2 weeks vs. 2 years.

Bill R — September 13, 2014

Wow, I have absolutely no reference in my own life to understand how a family member or close friend could be incarcerated and not be supported through regular visits. It's almost impossible to imagine the social environment such people exist in.

mn trautner — September 13, 2014

Last year, a group of graduate students and I visited Attica, and the prison guards told us roughly the same thing (though it was more along the lines of a small group of prisoners get a lot of visitors while most never get any visits at all). We wondered at the time if there were organizations that volunteered to visit with prisoners that don't get visitors, kind of like those orgs that arrange letters to be sent to random soldiers. The guards didn't see how something like this would be possible, though, due to requirements for names to be listed on prisoner contact lists, etc. We really liked the idea, though. Could something like this ever reasonably work? Or has someone already figured it out?

Shorties Untold – Bridget Magnus and the World as Seen from 4'11" — September 14, 2014

[…] du jour is puree of police violence and race issues with a hint of civil forfeiture, topped with prison visit data. Perhaps the lady would prefer our Cosmo-inspired salad with cranberry […]

WitnessLA.com » Blog Archive » Crime Decline Higher in States That Also Reduced Incarceration, California Foster System Behind on Investigating Mistreatment, Inmates Average Only Two Visits, and SCOTUS and Gay Marriage — July 20, 2015

[…] of Minnesota sociology professor and author, Chris Uggen, has more on the study for Sociological Images. Here’s a […]

Crime Decline Higher in States That Also Reduced Incarceration, California Foster System Behind on Investigating Mistreatment, Inmates Average Only Two Visits, and SCOTUS and Gay Marriage | wla — January 18, 2016

[…] of Minnesota sociology professor and author, Chris Uggen, has more on the study for Sociological Images. Here’s a […]