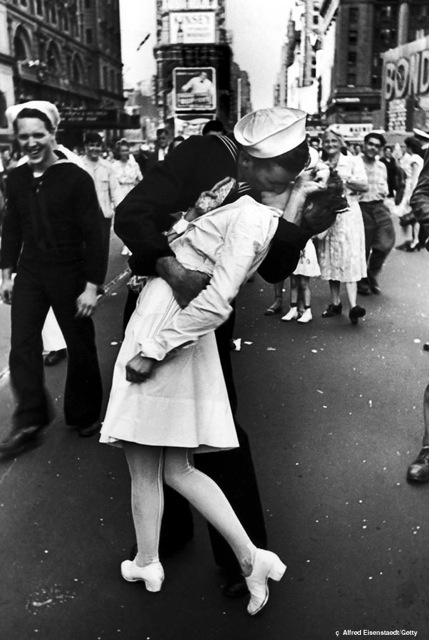

The photograph of a sailor kissing a woman on V-J Day in Times Square is an iconic one. Taken by photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt in Times Square on August 14, 1945, it is probably one of the most memorable images of WWII. As the Japanese surrender, the image seems to capture the jubilation at the end of a long war:

The image has become ubiquitous; you can buy it on posters and Valentine’s Day cards. Couples have re-enacted the famous image in Times Square. After the repeal of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell in 2012, the photograph was compared with one of a gay Marine kissing his boyfriend after returning from a tour.

Recently the people in the original photograph were identified. From their story, we now know that George Mendonsa was on a date with another woman when the Japanese surrendered. After a few drinks at a nearby bar, he went out on the street and grabbed Greta Zimmer Friedman for a kiss. According to the Mail Online,

“The excitement of the war being over, plus I had a few drinks,” he told CBS. “So when I saw the nurse, I grabbed her, and I kissed her.”

The article continues with an explanation of Friedman’s description of the experience:

“I did not see him approaching, and before I know it, I was in this vi[s]e grip.” Of course, that moment of wild elation, gratitude and passion was captured by LIFE photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt.

Later in the article, Friedman states,

That man was very strong. I wasn’t kissing him. He was kissing me.

Does a strong man grabbing a woman on the street in a “vise grip” and kissing her describe “wild elation, gratitude and passion”? Or does it describe a case of sexual assault? Feministing blogger Lori argues that the photograph does not capture the romantic moment that we believe it does. After reading her argument and studying the picture, I don’t think I could ever see it as anything other than the depiction of public sexual assault. As Lori argues,

A closer look at the image in question shows corroborating details that become stomach-turning when properly viewed: the smirks on the faces of the sailors in the background; the firm grasp around the physically smaller woman in his arms such that she could not escape if she tried; the woman’s clenched fist and limp body.

Knowing the context has changed the meaning of the photograph. What was once read as the depiction of spontaneous romance at the end of WWII can now be read as one of spontaneous sexual assault.

The context of war also matters here. During war women typically hold roles that are supportive to men — supporting the war effort or supporting men sexually during war. As Cynthia Enloe argues in Maneuvers: The International Politics of Militarizing Women’s Lives, militarization relies on constructions of masculinity and femininity that make women both victims who need protection and objects to be sexually oppressed. The sailor in the photograph is hyper-conforming to wartime masculinity. He grabs the nearest nurse and kisses her to celebrate the end of war.

It is an iconic image, just not for the reasons we always thought it was.

Comments 25

Leslee Bottomley Beldotti — October 5, 2012

I guess the next shot of her resoundly slapping him was discarded because it didn't fit the photographer's narrative?

Thomas Gokey — October 5, 2012

I had always suspected that they were strangers to each other. It's nice to finely get the story behind the image. Like you said, it's an image of war. This has always been part of what war is, it's part of the shame of war.

Karen Miller — October 5, 2012

There's a giant--GIANT--statue of this kiss near the San Diego harbor. It was titled "Unconditional Surrender." Here's a picture of it from the Quirky Travel Guy website: http://quirkytravelguy.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/kissing-sailor-statue.jpg

My grandmother was a teenager in NYC on V-Day, and she and her sister had to wait for two hours in a store on their way home from school because they were being grabbed right and left. It was not her favorite day.

R Hall — October 5, 2012

I've never liked this photo; the woman always seemed too powerless, puppet-like and contorted, and the fact that the 'embrace' is utterly one-sided and her left hand almost a fist ... When I later found out the provenance, it certainly fell in place.

I really liked the comparison someone did of this and the Gaeta-Snell kiss. How much sweeter love looks :)

Megan C. — October 5, 2012

I remember seeing a brief clip from an interview with this woman 5+ years ago on TV. The tone they portrayed from her was much different in that clip - much more "oh that's just what people were doing that day," in a sing-songy kind of way. I think that says something about the power journalism has in either influencing or challenging cultural tropes. It seems this time, a larger snapshot of her real experiences of the kiss made the final cut.

decius — October 6, 2012

What the picture represents is not what the picture is of. Just like the flag-raising photograph, among other propaganda of the time.

mimimur — October 6, 2012

It's really striking that this picture of sexual assault holds so many tropes of ideal romance in the way that the nurse is postioned. Tilted back is code for passion, a foot half lifted for femininity. Now we know that it's all due to powerlessness, being tilted back and losing her footing means that she can't just break free, because she'll fall to the ground of she does. Contrast the images shown of the consensual kisses here, where everyone (except the one meant to mimmick the photo) has a secure balance and noone uses that vice grip on their partner, because they'll get that kiss anyway. How interesting that it is the blatant power imbalance that is code for romantic, not two people approaching each other on equal terms and free will.

biff — October 6, 2012

Considering the photograph in isolation robs it of the richer context, which involved a spread of V-J pictures in the Aug 27, 1945 issue of _Life_ (it's available for viewing on Google books). In it, one can find the original caption for the Times Square photo, which says that the nurse "clutches her purse and skirt as an uninhibited sailor plants his lips squarely on hers" (p. 27).

On the prior page, however, one sees another impromptu coupling in Miami, in which "a longing, determined sailor grabs a willing light-o’-love and hoists her into position for a prolonged, determined kiss." The caption says "willing," but as she has been swept off her feet and we can’t see her expression, it’s hard to say.

Above the Miami image, in contrast, are photos from celebrations in Washington and Kansas City, where the embraces look to be more consensual. The latter caption, in fact, says that the GI in question is "just passing through Kansas City, [and] gets well bussed." That picture is open to interpretation, but one could easily conclude from their positioning and body language that the implication in the caption is on target: she is asserting herself, rather than the other way around.

After all these years, the Times Square kiss has become separated from its sibling images. The other photographs in the montage might not change feelings about the famous shot, but they do offer a wider perspective for assessing it. I'd be curious to see if viewing them all together makes any difference for others.

Donald Frazier — October 6, 2012

True that. But it works both ways. Relatives who were in wartime situations, men and women, say that everyone had a free pass for as much sex as possible and many things like this were expected, forgiven, and often reciprocated. My aunt in law in Alsace says she spent the night in a US serviceman's tent and the next morning saw half the girls in the village emerge from the others. In The Warriors, J. Glenn Gray says it is a primal drive in wartime to regenerate the species. James Jones books good on this too, as were the stories of my grandmother who worked in a factory making bomb casings.

fork — October 6, 2012

You write: "From their story, we now know that George Mendonsa was on a date with another woman when the Japanese surrendered. After a few drinks at a nearby bar, he went out on the street and grabbed Greta Zimmer Friedman for a kiss."

The Mail Online writes: "Mendonsa and his date, who would become his future wife, rushed to a nearby bar where the sailor admits he ‘popped quite a few drinks.’

As they set on their way, Mendonsa spotted a woman in a nurse’s uniform - he left Petry and rushed to grab her."

"He went out on the street" rather than "They went out on the street" sort of leaves the impression that Petry was not by his side, and that, in the excitement, he grabbed the nearest woman. But if the Mail account is correct, his date was right there, available for assault. He was not so excited that he spontaneously grabbed a victim. He actually made a selection there.

And about the excitement. I'd always thought that what happened was people heard the war was over, there was jubilation in the streets, and the guy grabbed the woman when he heard the news. But he had time for "quite a few" drinks in between hearing the war was over and assaulting someone. What an opportunistic creep.

And the Mail saying that they've never once reenacted the kiss? I think I need to take a shower.

Sila Mahmud — October 7, 2012

wow.. Fantastic steps.. I really like it. keep up :-)

Gilbert Pinfold — October 8, 2012

Maybe for the first time on this blog, I find myself swimming with the mainstream here... Lost for words.

Wednesday, October 10 – Reading Round-up - Feminish — October 10, 2012

[...] The Kissing Sailor Photograph: An Iconic Image of War, Not Romance: I, personally, grew up well-aware of this iconic photograph, seeing it everywhere from restaurants to textbooks, but never knew the real story behind it, and the severity of its circumstances. [...]

Mädchenmannschaft » Blog Archive » Das legendäre “Kissing Sailor”-Foto bildet Gewalt ab, keine Romanze — October 12, 2012

[...] weitere Einordnung der Ikonographie gibt es bei Sociological [...]

Guest — October 15, 2012

A confession- I did have this poster on my dorm room wall. Taking this post into account, I do see cause for concern.

So, for those of you (like myself) who no longer feel comfortable with the Times Square photograph but retain a liking for romantic black and white images I want to share my replacement!

As an alternative I chose a poster of one of my favorite sculptures: Rodin's The Kiss

http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/103439.htmlhttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Kiss_%28Rodin_sculpture%29

Rodin's sculptures really allow and benefit from extended observation and I feel that this image is great- positive, beautiful, and romantic.

I like how her arm curves around his neck- how obviously into each other they both are.

Their bodies are both relaxed and engaged; to me it is a beautiful image of a private moment.

For the architecture nerds out there, Louis Kahn proposed to his wife in front of this statue in Philadelphia.

tralalalalalala37 — January 4, 2013

This type of kissing isn't sexual. What tripe.

Fotografija mornara koji ljubi medicinsku sestru: ikonska fotografija rata, ne romanse » Centar za društveno-humanistička istraživanja — February 28, 2013

[...] http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2012/10/05/the-kissing-sailor-photograph-an-iconic-image-of-war... Autorica: Wendy Christensen Prevela: Petra [...]

Sociopress.cz » Fotografie líbajícího námořníka: ikonický obraz války, ne romance — March 18, 2015

[…] Zdroj překladu: The Kissing Sailor Photograph: An Iconic Image of War, Not Romance […]

Fotografie líbajícího námořníka: ikonický obraz války, ne romance | Sociopress.cz — October 4, 2015

[…] Zdroj překladu: The Kissing Sailor Photograph: An Iconic Image of War, Not Romance […]

The Iconic, Yet Ironic, V-J Day Photo – Cultural History of the Internet — October 29, 2021

[…] Posted by mminter6 The Iconic V-J Day Photo. Images Taken by LIFE Magazine. […]