Referring to the controversy over Pluto’s demotion, in this quick video C.G.P. Grey does a fun job of explaining why the icy rock is no longer a planet. He closes with a discussion of why properly categorizing objects in space with words like “planets” may always elude us. It’s a great example of social construction.

Referring to the controversy over Pluto’s demotion, in this quick video C.G.P. Grey does a fun job of explaining why the icy rock is no longer a planet. He closes with a discussion of why properly categorizing objects in space with words like “planets” may always elude us. It’s a great example of social construction.

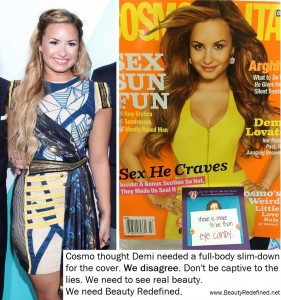

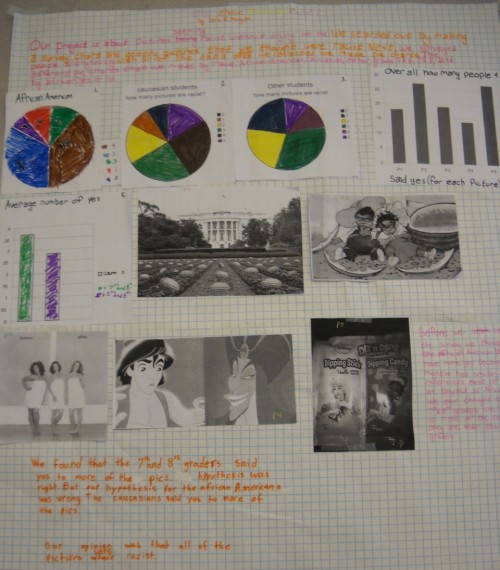

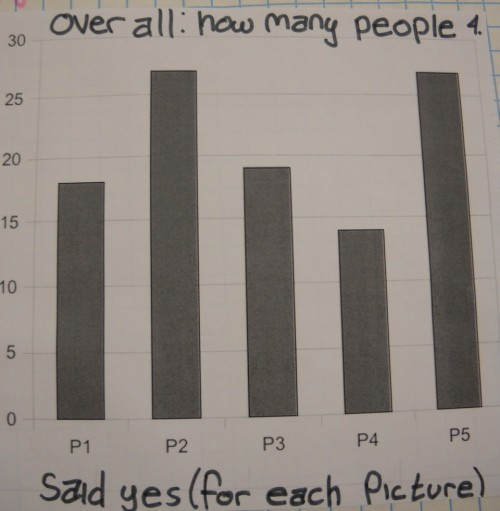

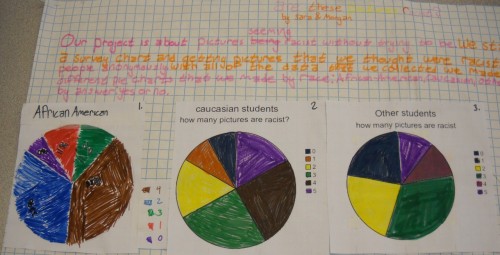

Via Blame it on the Voices. For lots more examples, see our Pinterest pages on the social construction of everything and the social construction of race.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.