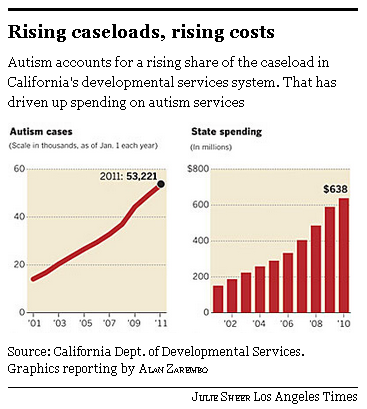

Autism appears to be on the rise. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that there are 20 times more cases of autism today than there were in the 1980s. This figure, from the Los Angeles Times, shows a 200% increase in California:

The rise in cases of autism led scientists to ask whether there was an actual increase in incidence or if we were just getting better at identifying it. The evidence seems to suggest that it’s (at least mostly) the latter. Said anthropologist Roy Richard Grinker: “Once we are primed to see something, we see it and wonder how we could have never seen it before.”

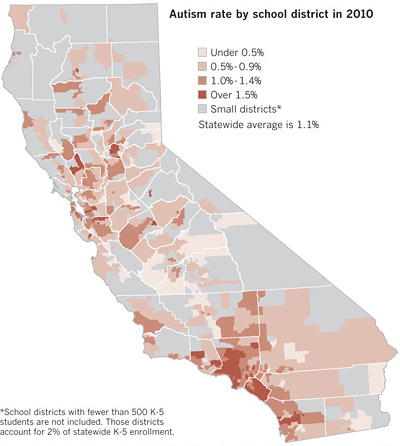

But how to explain disparities like this?

Often regional differences in health and mental health can be traced to heavier environmental toxin loads. In most of those cases, though, clusters of illness occur in poor and often disproportionately non-white neighborhoods. Autism clusters were happening in class-privileged places.

Sociologist Peter Bearman discovered that these clusters were the result of conversation. Class-privileged parents had the resources to get their child diagnosed, then they talked to other parents. Some of these parents would recognize the symptoms and take their child to the doctor and… voila… a cluster. “Living within 250 meters [of a child diagnosed with autism], reports the Los Angeles Times, boosted the chances by 42%, compared to living between 500 and 1,000 meters away.”

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 28

Andrew — March 21, 2012

It makes you wonder if autism is even a legitimate diagnosis or just an upper class, 1st world, problem that we invented because we have the time to navel gaze.

We already did that with "ADD/ADHD". Obviously that can't be the only instance.

Mits — March 21, 2012

There's another major factor at play here that you haven't considered. In 1994 American Psychological Association released the DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual) which changed the classification of a number of mental disorders. In this edition, autism was changed from a specific disorder to a spectrum disorder, effectively increasing the number of people who are diagnosed with ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder). Those who wouldn't have been diagnosed with autism prior to 1994 now might fall under the ASD umbrella. Broaden the criteria, increase the number of cases.

For more info, you can read this study:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/117/4/1028.abstract

Anonymous — March 21, 2012

Most scientists attribute the rise in autism to diagnostic substitution as the medical literature has refined the definition of autism greatly in the recent decades. Furthermore, physicians have expanded the spectrum of autism. Relatively mild cases are now diagnosed as autism. In other words, physicians are diagnosing autism whereas in the past they would have previously diagnosed a child with another learning disability or mental retardation. See for example Shattuck's paper in Pediatrics:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/117/4/1028.full

The neighbor stories aren't particularly surprising. Mild cases of autism are often thought of as the kid is just "weird" or "a bit slow." If a parent is exposed to another child who is similar, they make seek a doctor who may make a diagnosis - which explains the neighbor correlation.

The socioeconomic distribution of autism is more complicated. One thing he know is that autism tends to be correlated with age of the parents (though we don't know enough to say if it plays a causal role). Poor and minorities often have children at younger ages, possibly making them less vulnerable. It's been a while but I recall a study from the 1990s that suggest a person's race or socioeconomic status bias diagnostic assessment. If a kid was poor or minority a non-trivial proportion of doctors were inclined to think a kid was just stupid rather than developmentally delayed or suffering from a learning disability, even though the sample cases fit the diagnostic criterion. A similar phenomena certainly seems plausible in the case of autism. By far the most common hypothesis is that wealthier and more educated people simple know more about the symptoms and have better access, making them more prone to discuss it with their doctor.

C W — March 21, 2012

"The rise in cases of autism led scientists to ask whether there was an actual increase in incidence or if we were just getting better at identifying it"

We're not exactly "getting better at identifying it" so much as we identified it as MANY other things entirely in the past.

Anonymous — March 21, 2012

Does "better at diagnosing autism" include skill at diagnosing autism regardless of its presence?

I think a significantly higher proportion of people diagnosed with autism instead exhibit symptoms which superficially resemble those of ASDs, but do not share the same proximate cause. I base that conclusion on a fair number of people I know who have been professionally diagnosed and later professionally told that diagnosis was in error.

Anonymous — March 21, 2012

I work for an agency that provides residential, habilitation and respite services to individuals with severe to profound developmental disabilities, including autism. Virtually all of the individuals I work with have received diagnoses of autism in addition to other developmental disability or mental health diagnoses such as MR or social anxiety disorder or schizophrenia. Many staff, including myself, have wondered about the autism diagnoses of some of our individuals in the past, as many of them appear to primarily exhibit behaviors that could better be explained by their other conditions. The response I have heard repeatedly from administrators, psych staff and others who have been with the agency for a long time is that there had been an agency wide push in the past few decades to get autism diagnoses for everyone who we provide service to because the diagnosis would open up new and different funding streams for our programs. Since our agency is relatively small and underfunded, it seems plausible that this could have happened. Combine this with the broadening scope of the definitions of autism, and I think this illustrates how diagnosis can be strongly influenced by external factors.

Anonymous — March 21, 2012

The "living nearer to another child with autism has higher rates of autism" may also be a different side of the "we're better at diagnosing it" coin. I know quite a few people who grew to adulthood with milder forms of autism and just never knew, and had never really heard of their situation having a name until then. I know people who flat out don't believe that people with autism can speak, let alone hold jobs and have adult social lives. If a parent has always believed that autism means that, why would they think a kid with a more mild form of autism wasn't just "sort of different" or "more difficult to handle than other children?" But if the family next door has a kid with a milder form of autism, and they know it, it might come up in conversation.

Ben Zvan — March 22, 2012

I recently read that prenatal vitamins have been shown to reduce the risk of autism. I wonder how many poor women take prenatal vitamins.

Caragh — March 22, 2012

Partly medicalization, partly environmental (Columbia recently found in a study that there was a significant correlation between it and inflammation. This is true for cancer, as well, although that was not a part of that specific study).

Emeraldislejen — December 11, 2012

Isn't California being pushed to have more cities add fluoride to their water? What has been the increase, in adding fluoride, in the last decade? Can you compare a map of CA cities with fluoride to the map of autism rates?