Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

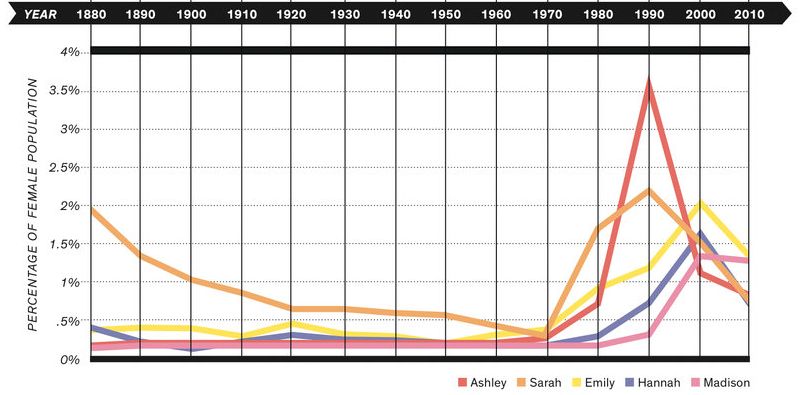

In Sunday’s Times, David Leonhardt, who usually patrols the economics beat, looks at fashions in baby names. His primary focus is the rapid decline in old-fashioned names for girls. The “nostalgia wave” of Emma, Grace, Ella, and other late-nineteenth-century names, he argues, is over.

Well, yes and no. Sarah and Emma may be in decline, but the big gainer among girls’ names is Sophia, an equally nostalgic name that was last popular at the turn of the twentieth century. Isabella, too, (third largest gain) follows the same trend line. Besides, the nostaligia for old names was selective. Emma and Grace may have come back, but many other old-fashioned names never became trendy. One hundred years ago and continuing through the 1920s, one of the most popular girls’ names in the US was Mildred. (You can trace the popularity baby names at the Census website.)

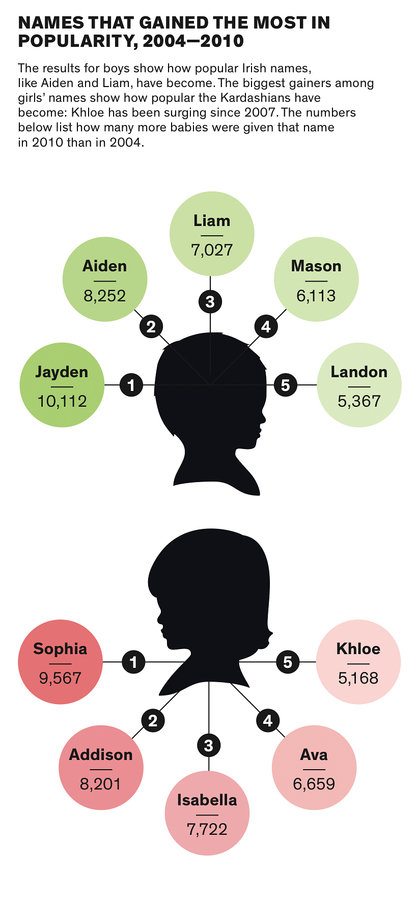

“The lack of recent Jane Austen movies has probably played a role,” says Leonhardt, though he’s probably joking. Not only is Emma still in the top five, but I suspect that films of that persuasion appealed more to the prejudices and sensibilities of post-childbearing women. But the media do have an impact. In Freakonomics, Levitt and Dubner showed how fashions in names often trickle down. The Sophias and Isabellas become stylish first among the upscale and educated; it may be several years, even decades, before they became more widely popular. But the media/celebrity channel can bypass that slow trickle. As Leonhardt says, how else to explain the boom in Khloe?

Similarly, Addison, the second biggest gainer, may have gotten a boost from the fictional doctor who rose from “Gray’s Anatomy” to her own “Private Practice.” In the first year of “Gray’s Anatomy, the name Addison zoomed from 106th place to 28th. The name is also just different enough from Madison, which had been in the top ten for nearly a decade. Its stylishness was fading fast among the fashion-conscious.

Madison herself owed her popularity to the media. She created a big “Splash” soon after the film came out. As Tom Hanks says in the scene below, “Madison’s not a name.” (Stop at the punchline at 3:23 — “Good thing we weren’t at 149th street.” Transcript after the jump).

At the time, the Hanks character was correct. Before “Splash” (1984) Madison was never in the top 1000. The next year, she was at 600. Now she has been in the top ten for nearly fifteen years, and at number two or three for half those years. (There have not yet been any Madisons in my classes. I suspect that will change soon.)

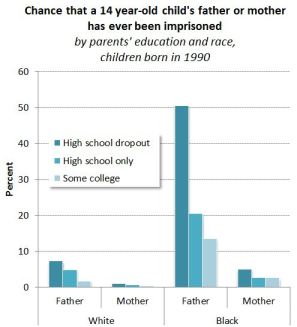

Boys’ names seem governed by somewhat different rules, with less overall variation, though recent trends are towards names with a final “n” (four out of the five big gainers in the chart above) and Biblical names.

In short, these recent changes in girls’ names aren’t about nostalgia. Name trends are like fashion trends, they come and go. And, like fashion, name trends can be media driven, especially now that media can short-circuit the slower class diffusion process.

Transcript of the Splash joke after the jump: