Much has occurred in the months following the initial media frenzy surrounding Trayvon Martin’s death. George Zimmerman, whose ethnicity was later re-classified as “Hispanic,” was eventually arrested for second-degree murder and is currently out on bond while awaiting trial. His wife has been charged with perjury for lying about their finances (and the over $200,000 sent to them for legal defense by sympathetic citizens) in a bail hearing. Discussions on “stand your ground” laws abound. And there’s even been a public backlash against Martin’s presumed innocence in his death, with numerous reports claiming that he was a juvenile delinquent. Others felt his “hoodied” look had made Martin appear threatening, and thus perhaps deserving of being profiled.

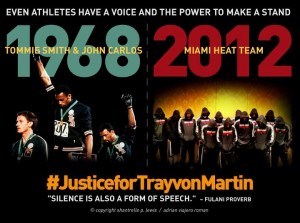

The “hoodie,” in particular, has become an important symbolic tool for those seeking justice for Trayvon Martin and his family, as well as others like him. Thousands of individuals, ranging from professional basketball players to white suburban youth, have sported hoodies in solidarity.

We called on a number of prominent social scientists to discuss the aftermath of Trayvon Martin’s death, examining the multiple narratives that have factored into media coverage and public responses. We started by asking our panelists why they thought Trayvon Martin’s death elicited such a large public response, especially among white, middle-class Americans.

Aldon Morris: The middle-class image of Trayvon Martin and the middle-class quality of the response by his parents are largely responsible for the extraordinary [public] response. The early images of Martin depicted him as a young, innocent, handsome, wholesome, gentle kid that all parents, friends, and relatives [would want to] embrace and protect… middle-class America [thought] “this kid looks and acts like my own son despite being a young black male.”

Trayvon’s mother and father also looked and acted like decent middle-class parents. They spoke good English, dressed in middle-class garb, and portrayed no threatening black militancy. Yet, though persistent and vociferous in their outrage, Trayvon’s parents spoke softly and movingly conveying a grief that tugged at the hearts of ordinary people… The Martins pulled off a near miracle in white America… they were able to subjugate their blackness to their humanity.Charles Gallagher: Trayvon Martin’s death has struck such dissimilar cords with black and white America because both groups see race relations, treatment by law enforcement and the ability to attain the American dream in starkly different terms. For much of white America, this is a case of cognitive dissonance; [they believe] race-based discrimination and institutional racism are actions of the past. While the nearly 200 million non-Hispanic whites in the United States are an extremely diverse lot, national polling data on their attitudes and perceptions concerning race, race relations, and the relative socio-economic mobility of blacks point generally in one direction: that the …nation has transcended the caste-like trappings of race and is now best defined by “colorblind egalitarianism.” This means most whites have come to view race as a benign social marker…. Most importantly in this “leveled playing field” perspective is that, just as blacks are no longer socially or economically disadvantaged in any systemic way… whites are no longer privileged by their whiteness.

[Still, though] there is no shortage of objective measures that demonstrate racism is still very much interwoven into the fabric of our social institutions. Who gets “stopped and frisked” or is targeted for predatory lending or must deal with the effects of environmental racism? It’s disproportionately minorities. The cognitive dissonance … is reflected in the stark racial differences in recent polling data concerning the death and treatment of Trayvon Martin.

Zenzele Isoke: The media’s fixation on “white middle America” is an example of one of the ways that the American media upholds white supremacy—a political and economic system that upholds the privileges of those who are white and/or enjoy white privilege. This needs to change. I think that too little of our discussion is centered upon the experiences and perspectives of people of color—especially poor and working-class people of color who are routine victims of racial profiling and other forms of government-endorsed racial terrorism. I believe that the media should be more concerned about how African Americans, Latinos, Pacific Islanders, and Native American people feel about Trayvon’s Martin’s murder. More of the conversation should be based on why there has been such a poignant and heart-wrenching response in these communities, especially in various African American communities—wealthy and poor, urban, rural, and suburban. Why has there been such a huge response in our communities?

Enid Logan: Unlike many other parallel tragedies, I believe, this case elicited a large public response because it fit into a familiar and galvanizing narrative about what racism is and what a “good person” should do about it. In addition to there being a readily identifiable white racist in this narrative, there was also a pure, unblemished black victim in the person of Martin.

Participants went on to tell us they had wished for a more nuanced, critical media discussion about race, particularly in relation to violence committed against people of color.

Logan: This death should lead us to think more deeply about the racial implications of so-called “race-neutral” —like the “stand your ground” ordinance—[laws] throughout the country. A manifestation of the institutionalized and covert nature of modern racism, our “colorblind” legal system often functions in ways that discipline, punish, exclude, incarcerate, or justify the murder of non-whites in particular. Furthermore, so-called “black-on-black violence” has been wrongly declared out of bounds in this discussion (see, for example, Khalil Gibran Muhammad’s April 5 editorial in the New York Times). As George Yancey and others have written, it is very hard to “see” black male bodies in any way other than as suspicious, threatening, out of control, and in need of containment and discipline. If we really care about the untimely deaths of so many black youth, then we cannot limit the conversation only to cases involving so-called “white racists.”

Isoke: What has not been sufficiently covered is an overall mapping of the number of deaths committed by law enforcement officers, and in George Zimmerman’s case, “wannabe” police officers who racially profile, target, and kill African American and Latino youth. For instance, why haven’t the media and federal agencies compiled national statistics about the number of unarmed people of color—African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans—who have been killed by the police? George Zimmerman, in my opinion, represented the sentiment held by many working class white men, that young black people are a threat. This is why so many white people—specifically white men who work in law enforcement—spoke out in support of Zimmerman. And although I can’t prove it (no one can), I’m certain that those are the people who donated to his defense fund. I would bet on it, and I’m not a gambling woman!

[So] why doesn’t the media begin to think about these frequent killings—and in some cases, targeted assassinations—as forms of state sponsored terrorism instead of so-called “justifiable homicide?” Also, I feel like the media doesn’t give enough air time to organizations—social justice organizations—other than the NAACP, the Urban League, and the Congressional Black Caucus. There are organizations in cities and urban communities across America who take a lot of time to document and study racial profiling and other forms of police brutality that result in the maiming and killing of young black people. [These include] organizations like Communities United Against Police Brutality, the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, the Audre Lorde Project, Occupy the Hood, and so many others.

Morris: The reality that what happened to young Trayvon Martin is commonplace in America and not an anomaly [wasn’t] covered sufficiently. [It seemed as if his death was] a horrendous but isolated tragedy. During a town hall meeting in Sanford, Florida shortly after Trayvon’s murder, a distraught black mother cried out that her son had been murdered just a few months prior …but no outcry for justice took hold. It was the kind of story that should have made the …news. Yet, there was no coverage at all and certainly not a discussion regarding whether Martin’s death was a link in a long chain.

Many storylines were adopted by the media and the public in discussing the Trayvon Martin case. Initial reports focused on Trayvon Martin’s apparent innocence (as both the victim and a minor), George Zimmerman’s presumed guilt, and the shooter’s contested whiteness.

Morris: The initial media coverage focused … [on a] compelling storyline …that this promising, unarmed kid had been needlessly struck down by Zimmerman, a much older and armed white man. Details of Zimmerman’s background, family life, and character trickled out slowly in comparison to Trayvon’s, and even [months later] not a great deal of personal information is known about what kind of person Zimmerman is. This initial coverage helped foster a saint/devil scenario that is always good copy for the media; it helped trigger the enormous response.

But this storyline is not static. The media [later began] to suggest that maybe we have a false image of Trayvon–[maybe] Trayvon should be viewed as a pot smoking, poor performing, rebellious student prone to violence …maybe Trayvon was more like violent young black “thugs” than what we were led to believe. Images of Zimmerman, on the other hand, are beginning to suggest that maybe he faced a young violent black monster …intent on killing him. Thus, Trayvon represents the nightmare that many white Americans wish to avoid at all costs. These competing storylines will become even more important as this case is adjudicated.

Logan: Trayvon’s innocence was most powerfully established via the photographs that were circulated of him as a child and as a tween, wearing an earnest expression, and/or a football uniform, [even] though he was 17 at the time of his murder. He was carrying in his pockets only Skittles and iced tea, we were told, he’d gone to the store for his little brother, he was an honor-roll student, and his family was non-poor (i.e., either upper-working or lower-middle class). Thus the murder fit into a Civil Rights era narrative about white-on-black violence—a narrative about innocent black children being gunned down by white racists. Hence the parallels to Emmett Till and the four little girls killed in Birmingham.I make this point not to imply that Trayvon was “less than innocent,” and therefore in some way responsible for his own death. My argument, rather, is that Trayvon’s extreme innocence was a precondition for the recognition of his humanity. The body of 17-year-old Trayvon was supplanted by that of him as a child, because at puberty his body had lost even the plausibility of innocence (Beverly Tatum discusses this in her 2003 book Why are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?). The child Trayvon could be granted provisional whiteness: the presumption that he had a right to be in whitespace, that he may not have been up to no good, that he could have just been a boy walking home in the dark. By championing a black victim who had been wronged by racism, the liberal press could (as it had during Barack Obama’s presidential campaign) celebrate its “thoroughly confirmed” commitment to racial tolerance and justice.

But the almost romanticized notion of an ideal white racist/black victim began to fall apart as the starkly dichotomous framing of the case was complicated and as Trayvon [came to be] viewed as less than saintly. Consider the impact of the finding that he had been suspended from school at the time of his murder. As Trayvon’s father stated, the question should not be why was he on suspension, but why was he killed!

Isoke: These “storylines” are techniques the media uses to garner attention; [they] are contrived and help absolve the media of its own responsibility in presenting the truth, as well as the real life social consequences of its coverage.

The truth is that, yet again, an unarmed black man was killed by a white man for no other reason than the young black male was considered a threat. Zimmerman carried a live firearm to protect himself from those he feared. He acted on his fear in the most horrific way and shot Travyon dead. That is tragic. The political community, including the media, should recognize this simple injustice. When the media panders to both sides or both “storylines” … it makes a mockery of the political community. The media operates on the fiction that both sides are “equally valid,” when clearly they are not.

What about the “hoodie movement” and the eventual cooptation of the “hoodie” as an emblem of racial oppression and human agency?

Isoke: Every symbol of resistance and freedom struggle gets co-opted. That is no surprise. It can even be a good thing. I even wore a black hoodie in support of Trayvon, and I never wear hoodies! I was glad to see people of many races and economic backgrounds wearing the hoodie. I felt as if there was a part of people who recognized the injustice and the reality of race-based oppression in the United States. I saw Christians, Muslims, granola folks… everybody wearing the hoodie. It felt good. I hope that everyone who sported the hoodie… will take that sentiment and challenge racial profiling by citizens and law enforcement alike—then translate that into sound public policy. I hope that citizens begin to call for the prosecution of police officers who abuse and kill innocent civilians… of prosecutors who railroad poor black and brown people into prison.

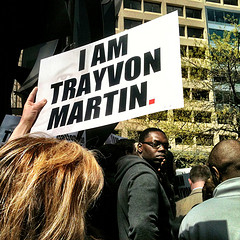

Logan: I would argue, rather than being an expression of colorblindness among whites, the “hoodie movement” was all about race. The “hoodie” today is a clearly identifiable trope of hip hop culture and urban black masculinity. Charles Gallagher writes about white youth… believing that through the consumption of racialized cultural artifacts (music, clothing, foods, etc.), they may experience what it is to be a person of color. Race is understood by whites as pertaining to culture, rather than mapping onto a privilege and power hierarchy from which they directly benefit. [So] yhe appropriation of the hoodie and claim to “be” Trayvon Martin was both an appropriation of black racial authenticity and an aspect of the consumption of blackness in the twenty-first century. Recall that most everyone standing in their hoodie was looking “mean” or “serious”—like the prototypical, pissed-off urban black male. Why was no one smiling? Why not emphasize the youthfulness of Trayvon? While white youth in the 1960s traveled to the Deep South to participate in the Freedom Rides and put their very lives at risk, there are no such costs associated with [today’s periodic] forms of anti-racist activism (i.e., “I am Trayvon Martin” and “Yes We Can!”).

To conclude, panelists reflected on what the events following Trayvon Martin’s death said about the current state of American race relations.

Gallagher: According to Gallup, a majority of white Americans (51%) believe that race did not play or played only a minor role in the initial confrontation or shooting of Trayvon Martin. By the second week of coverage… a near-majority of whites (43%) said there was too much coverage of Martin’s death. Perhaps these white responses reflect racial fatigue or the news overexposure of a topic given our 24/7 media cycle. It may, however, reflect the anxiety, misdirected anger, or even shock that, in the age of perceived colorblind egalitarianism, a young black man minding his own business in his dad’s development, “armed” with a can of ice tea and Skittles, could be forced into a deadly encounter because of his skin color.

Isoke: I think there is a critical mass of people—possibly even a majority—who understand that racism and racial violence (especially state sponsored racial violence) is an ugly smear on this country’s history and its reputation today. I think that the “activist” response was predictable, but I think that the widespread community response was a bit different. …There are so many Americans who are sick of the senseless killing of African Americans, especially African American men. America is more diverse and racially progressive than we are led to believe in the media—this is another symptom of white supremacy. I think that many Americans, regardless of race, are outraged at Zimmerman’s behavior, as well as the behavior of the Sanford Police Department and the so-called “Stand Your Ground” law. Many Americans are appalled and outraged that citizens are permitted to walk around with loaded pistols waiting for something bad to happen so they can pull out their weapon and shoot someone.

However, the media doesn’t cover this enough. It’s like the side that stands for peace, tolerance, and non-violence doesn’t get heard over those who advocate policy positions and attitudes based upon fear, intolerance, and ignorance about people who are poorer, less privileged, and less racist. Those who talk the loudest, who invoke the most fear, and who have the most money, get heard. This needs to change in our political community—and the media is clearly a vital part of this political community.

Logan: The Martin case, as presented by the liberal (i.e., not right-wing) media, was very much a case of “low-hanging” fruit. It did not represent a progressive or race-critical response to contemporary racial injustice. It involved an easy “boogeyman,” an identifiably “racist” individual who shot and killed a black youth due to his “clearly held” racial prejudice. Zimmerman viewed an innocent child as “suspicious” and threatening. He may have even “uttered a racial epithet.”The activist response among non-blacks and the liberal media, in my view, was largely about righting an individual wrong. It did not involve a broader recognition of the workings of white privilege, the ways that past injustices contribute to entrenched present-day inequities, or how certain places and institutions are seen to be “white spaces.” Note, in the ostensibly well-intentioned “hoodie” movement, the thousands of white activists proclaiming “I am Trayvon Martin” rather than “I am George Zimmerman.” The later statement would have implied a truer, more honest understanding of the relations of power, privilege, and economic and social violence that contribute to the devaluation of black life.

Morris: It is possible that the Trayvon Martin case will reinforce racial oppression in the United States… the typical middle-class person will conclude that we, as Americans, will not stand idly by when racial wrongs occur. There will be a sense that in post-racial America [Trayvon’s death was an aberration]… Martin Luther King’s dream is a reality. The problem is that the case will be treated as a terrible anomaly that is not deeply rooted in a reality in which black life in America is worth less than white life.

Comments 2

Letta Page — August 3, 2012

Enid Logan's quote about holding up "I am George Zimmerman" signs really leaps out at me here - if they ended with "...And I don't wanna be," I can totally see that becoming an interesting rallying cry. I can't stop thinking about it! Acknowledging privilege but in useful ways is definitely something that stymies me.

Friday Roundup: July 12, 2013 » The Editors' Desk — April 1, 2014

[…] “Thinking About Trayvon: Privileged Response and Media Discourse,” by Stephen Suh. A roundtable discussion from just months after Trayvon Martin’s death, this piece looks at media framing and public responses. […]