Identity is increasingly tied to the body. Advertisements for natural herbal supplements to improve body shape, scientific concoctions to increase libido, and surgical procedures guaranteed, if not required, to impress sexual partners fill email inboxes on a daily basis. The message is only slightly less overt in more public spaces. For instance, images of celebrities, models, and athletes displaying their chiseled airbrushed six-pack abs and cellulite free thighs guide customers down the checkout lane at the local big box grocery store. Large-font proclamations cover these bodies, suggesting your body and life could be the same, if you’d only buy the magazine and try the trendy new workout or diet explained inside.

While increased understanding of and ability to alter the body is cause for celebration for many, critical scholars including Bryan Turner and Susan Orbach have been quick to remind us that these advances have not always led to happiness and health. The ability to “conquer” flesh and bone continues to place more responsibility on individuals to maintain the proper aesthetic appearance. And, with the exponential growth in the number of “experts”—now including but not limited to medical scientists, nutritional experts, the beauty industry, yoga gurus, and spiritual counselors—the difficulty of making sense of the overwhelming and often contradictory amount of information about health and bodies only grows. While it would be rather crude to suggest that in a different time, or in a different place, there is or has been a natural body, Orbach’s claim that we have entered an era of increased body confusion seems particularly apt (2009).

On the one hand, sociologists have insisted that our relationship to our bodies and the pressure upon bodies to fit particular aesthetic ideals cannot be isolated from larger social and economic contexts. For instance, scholars Susan Bordo (1999) and Nick Crossley (2001) have examined how bodies have moved further and further away from being tools sculpted by manual labor to expressions of personal preference, cultural pressure, and the leisure time to devote to creating a “pleasing” body (whether that’s for yourself or onlookers). The body has become another object to be prepared for consumption.

Perhaps more important for more culturally oriented sociologists are the subjective and ideological dimensions of shifts in bodies that bring blame and shame or pride and plaudits. Often thought of as the most biological and personal aspect of social life, the body is always already shaped and defined—literally—through culture. In this chapter, we consider two recent talks with experts about framing and defining the proper body.

In the first conversation, Abigail Saguy discusses the dominant cultural frames that stigmatize and attach blame to fatness. Saguy helps us see how the experts we turn to and the language we use normalize and hide judgment damages others who may not possess the “appropriate” or “ideal” body type.

In the second conversation, Natalie Boero and C.J. Pascoe look more closely at the relationship between people’s experience of their bodies and medical ideas of “health.” The authors take us inside the online world of pro-anorexia communities, showing how the chat rooms create safe spaces in which individuals share knowledge, find support, and engage with and resist institutions condemning their bodies and communities.

The studies approach the cultural construction of the body on two very different scales and from two different methodological approaches. However, both turn to bodies to trouble our notions of propriety, health, and bodies—as well as how we see others bodies and self-presentation as illustrative of deeper aspects of the self, including moral fortitude and mental ability.

Saguy began by discussing the importance and difficulties of language about bodies:

There’s a lot of stigma and discrimination against people who are heavy and so, unsurprisingly, there’s confusion and disagreement about how to best talk about it. I avoid using the words “obese, obesity, overweight” unless I’m talking about how other people use those terms. The reason I do is because one of the main goals of this book is to problematize the common ways of talking about fatness as a medical problem and a public health crisis… all of these terms take for granted what I call a “medical frame” or a “public health crisis frame”. If you think about it, try to imagine someone who is obese and healthy. It’s inconceivable, it doesn’t make sense because the word ‘obesity’ already implies medical pathology. And so it makes certain things unthinkable, and these are precisely the things that I’m trying to get people to think about. Why do we medicalize and pathologize fatness? Is there another way of talking about it? Overweight? Over what weight? “Overweight” assumes that there’s a normative weight, a good weight and one can be over that weight and being over that weight is, again, a medical problem.I use the terms “fat” and “fatness.” And this is not a perfect solution either… but I’m taking a cue from the fat acceptance movement that has reclaimed fat and fatness as neutral descriptors. This is a common tactic of social movements, we saw this with the Black Power movement, reclaiming black as a neutral or even positive term, with queer, and we see also it with fat. I sometimes talk about “heavy” and “heavier.” Sometimes I use the word corpulence. Other words that people use I don’t use because they have argued and I agree that they’re euphemistic, which also implies that there’s something wrong with fat…

Saguy continued by reflecting on how discrimination against fatness is often overlooked:

We are in the midst of a burgeoning discourse on obesity and the obesity epidemic, and that this is a major public health crisis. And that discourse takes for granted, again, the idea that it is a problem, a medical problem [and] a social problem to be heavy and the solution is making fat people thin as opposed to, for instance, making thin people less prejudiced against fat.

Key to understanding the way fatness is treated by society is to examine the way it is framed. Saguy outlines the consequences of some various frames:

… [P]eople don’t even think they are using a frame when they say “obese, obesity, overweight.” They assume they are talking about a fact. ..,And what I try to do in the book is denaturalize that and say let’s take a step back and think about how and why we talk about fatness.

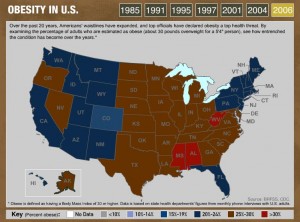

…So you can think about fatness as a medical problem, and that’s going to have implications: people need treatment, they need to change their bodies, maybe they need to take drugs or have surgery. You can think about; that that’s the medical frame. Or you can think that [fatness is] a public health crisis. That’s become very dominant since—but only since—about 2000. [In this frame], we need to have collective action, government action, to change population weight, to change behavior…

But fatness could also be portrayed as a civil rights issue, in which the problem is not that people, individuals, or the society as a whole, are too fat and therefore unhealthy. The problem is that there’s bigotry and discrimination on the basis of body size, and the solution is not to make fat people thinner, but to make the society at large more tolerant and even celebrate body size diversity.

[H]ow we frame this issue has very different implications for policy as well as for individual interactions and behaviors and for people’s lives. We’re all affected by this issue in different ways, those who are heavy, especially women, are most penalized by this; face discriminations, they are taunted, their dignity is denied on an everyday basis with strangers and intimate relationships with doctors. Those who are thinner, again especially women, thought this affects men, especially gay men, live in fear of becoming fat. And this can also be a real tyranny in their lives. These symbolic distinctions have huge material consequences.

What about the connections people make between fatness and moral failings?

…Peter Stearns, in his book Fat History, shows that at the end of the 19th century it was considered beautiful and desirable, especially for women, to be heavy. It’s about the turn of the century that it becomes cast as immoral… This history is somewhat contested, there’s a new book coming out, but it’s very clear at least that we start seeing a strong moral argument about fatness at the beginning of the 20th century. [It’s seen] as a sign of sloth and gluttony. This has not gone away. Now it’s combined with the medical and public health crisis frame. So, people take about people who are eating themselves to death: they are eating too much, they are gluttonous, they are slothful AND it has medical implications.

The moral judgment of fatness is often raced, classed, and gendered. It bears more than a passing similarity with the language used to decry welfare:

Weight is highly correlated with economic status; this is especially true for women. Once we consider, among people who take for granted that being fat is a medical problem, a public health crisis, who is blamed? Who is held responsible? I call these blame frames. The most dominant one in the U.S. context is that of personal responsibility. Here it’s the individual fat people who just can’t push away from the table. …[T]he discourse is very similar in terms of the “welfare queens,” and just poor people in general and their insatiable appetites. It’s very raced as well as classed, and politically it is used to say “well, should we be giving these people food stamps?” …It becomes a way of blaming the poor for their misfortune, for their health problems, as opposed to discussing the way, for instance, economic inequality or poverty leads to poor health outcomes.

The use of blame frames by media and public health outlets, Saguy tells TSP, only exacerbates the problem:

All this discussion on the obesity epidemic may be worsening stigma. And this is not just a social justice concern, but it’s also a health concern because we know that being the object of discrimination and stigma has negative effects on cortisol levels, on blood pressure, and ultimately on heart disease and life expectancy.

Many people, especially heavy women, perceive the doctor’s office as a hostile environment. They’re not treated with dignity. They are told that whatever health problems they are presenting have to be due to their weight (and… that it’s their fault). …This can be a life or death situation if a test could have discovered a [treatable] problem and instead the doctor says, “Come back when you’ve lost 50 pounds.”

…The fact that [New Jersey’s] Chris Christie could not be a serious candidate [for the U.S. presidency] unless he lost weight is very telling… “If he can’t control his weight, how can he run the country?” It’s definitely a moral judgment.

The way that he justifies health [as the] reason [for having a lap-band surgery] is very common. The socially accepted account of why people are losing weight [is that] they are losing weight to be healthy. But actually, a colleague of mine, Paul Campos… asked people if they could live longer, would they gain weight to add five years of their lives? They would not. But they were willing to give up years of life to lose weight. Again, it was not a random sample… But it suggests that losing weight for health reasons is what people think is acceptable, but it’s not the real motivation. …It’s interesting to ask now that we have our first black president, to ask, “Could we have a fat president?” Is the prejudice so great, still so great, that it would not be possible?

Where there are powerful frames, there are often opportunities for resistance to those frames. Saguy explains some efforts to offer alternative, more positive framing options for fatness:

…We have a strong tradition in the U.S. of talking about group-based discrimination, [but] there’s very little discussion of weight-based discrimination, and I think this is largely because the frames of medical problem and public health crisis frame are so dominant. The assumption… is that we have to make fat people thin [rather than accept them at their size]. The other two frames I talk about are the beauty frame in which, this comes from the idea of “Rubenesque”: …fat is beautiful… some are trying to reclaim that… [and] the health at every size frame. This is something that is very increasingly important among clinicians. And we see it among those who work with eating disorders as well as nutritionists and doctors. The idea that it’s not unhealthy to be fat, that you can be healthy at any size. We don’t want to treat the fatness, we want to, for instance, get people more active and tell them they can be active at any size. When we try to get people to exercise or change their diet to lose weight it’s usually unsuccessful… we’d do better to just focus on improving health.

While Boero and Pascoe also have an interest in the way weight, fat, and the body is framed, they take a different approach by examining web-based pro-anorexia communities:

Pro-anorexia communities are, in general, an online phenomena. They have migrated from email lists to individual websites and discussion groups, and they’ve cycled through various social networks, of different social networks, just like everything else has. They’re some sort of group, an interactive group, where members coalesce around an identity as being pro-anorexic. They identify as being eating disordered, having an eating disorder, but they generally see it as more of a lifestyle. They are generally not involved in any sort of treatment; many of them have never undergone any sort of treatment. They are looking for mutual support in crafting a pro-anorexia lifestyle and building a community.Because of the ephemeral qualities of the site and the migration of members from site to site so quickly, it’s next to impossible to get any sort of accurate count on how many people participate. But if you plug-in “pro-anorexia” or “pro-ana” into any sort of Google search, you will find hundreds if not thousands of sites.

Perhaps, not surprisingly, the sites have been a source of negative response and controversy.

It comes from politicians, parents, sufferers of eating disorders. For instance, in France there have been a lot of discussions about getting laws passed that make it illegal to encourage extreme weight loss in online communities. In the United States we haven’t seen laws passed per se, but Tumblr just came out with a statement with their goal of taking down these sorts of pro-eating disorder websites, or microblogs, on their site. You see online service providers also trying to sort of get rid of these sites, even if they’re not technically against the law. This is not new. Yahoo! was pressured to take down these sites 10 or 12 years ago. And interestingly, it’s also feminists who have very much had a negative response to these sites.

And, while the sites are not without fault, according to Boero and Pascoe, much of the criticism focuses on the most extreme aspects of the pro-anorexia communities:

I think overwhelmingly the media has whipped up sort of a moral panic around these [websites]. I don’t mean to sound glib here; eating disorders are a serious issue. [But the media has] sort of taken the most sensational aspects of these sites and put them out there as the Ground Zero for how people develop eating disorders these days. There’s been a very sensational reaction that has focused largely on the supposed desire of “veteran” members wanting to recruit… As these being breeding grounds for anorexia and bulimia and other disorders… as very predatory. [It’s] a very decontextualized moral panic—which is probably the definition of a moral panic. But really, [pro-ana sites have] largely been taken out of context, and the more sensational aspects have been focused on.

In contrast, to these popular accounts, Boero and Pascoe seek a deeper understanding of the sites in their research:

The year and half [we spent] looking at these sites really gave us a chance to look at the nuances…

We are absolutely guilty of looking at these sites and thinking, “Oh my goodness this is horrific! This is awful!” It did take us time—a lot of time, in fact—and I think if we had rushed and tried to get an article out as fast as possible, we would have been guilty of some of the things the mainstream media is in terms of not seeing things in context. I think that one of the things that [makes our research sound is how we became] so familiar with the conversations, the images, and the ideas posted on these sites over time, getting past the initial shock value… to see how a lot of the discussion mirrors more mainstream ideas about weight and weight loss and obesity. And that, to a certain extent, to understand the moral panic around pro-anorexia groups outside of the moral panic of obesity would be a missed opportunity because, if you look on these sites, once you get past some of the more extreme examples, what they’re telling each other to do is exactly what [mainstream society is] telling fat people to do. [Take] what we see as problematic in these communities, cut-and-paste it into a Weight Watchers website and it’s seen as legitimate practice around legitimate weight loss.

Boero and Pascoe explain that it is important for members of pro-anorexia communities to establish authenticity, but it’s complicated by the disembodied nature of a site about bodies.

Rituals are important, but some of the more concrete ways people [assert their legitimacy in these forums] is by displaying their knowledge about the disorders. Talking about their weight and statistics, talking about various side effects that they are experiencing from these disorders that would be characteristic of “real” anorexia. It’s a lot of constant reiteration of talking about their bodies, sharing images of their bodies, and using diagnostic categories to frame their bodies online and challenging other peoples characterizations of their bodies as well.

Some of the groups we observed required that their participants post or have pictures of themselves as their avatar picture or on their site to ensure authenticity. But a lower percentage actually posted pictures of themselves on the discussion groups, because a minority of group members actually posted on the discussion groups themselves [the others tend to read the sites and message boards without contributing]. That’s true across the board; there are more people who are members of discussion groups than actually post on them. [Still], if someone challenged your claim to bodily authenticity, you needed to produce a picture. And that didn’t even necessarily mean you needed to be successful. Someone could post a picture of themselves at a weight that they weren’t happy with, as long as they then did the interactional work of saying, “I’m fat and I want to be skinny.” It was more about participating in the discourse than proving you were actually skinny. You had to say you wanted to be skinny… or prove you are skinny.

[Surprisingly, these sites revealed] incredibly high levels of aggression. They were constantly policing the boundaries, and that’s where the “wanna-orexic” comes in. But they were also very intent on giving each other support in a kind way, in a sometimes humorous way and sometimes in a mildly aggressive way. If one participated in the discourse correctly, one could elicit all sorts of support. If one didn’t participant in the discourse correctly, that’s when you could get called out for being “wanna-orexic,” or not really anorexic.

Once a member has established authenticity, Boero and Pascoe explain, the pro-anorexia communities offer a non-judgmental space and a wide-range of resources for people who want to change their bodies. They report website members sharing dieting tips and ways to hide your eating disorder, how to handle your relationships, and what to do when another member doubted their commitment to body modification or sought help for their disordered eating.

A lot of times this support wasn’t just support in developing and maintain anorexia. But a lot of it had to do with managing symptoms, what to eat, what not to eat, dealing with family members and friends who were concerned about your eating habits.

We would usually see support for whatever people wanted support for. If someone was going into an in-patient program, people would say, “Good luck, I hope you get better.” But if people’s parents were forcing them to go into an in-patient program, they would say, “We’re so sorry you’re going through this, parents don’t understand, nobody understands this.” If a person had established themselves as authentically eating disordered, not just looking for a diet, they generally received support for whatever they asked for support for.

Participants also used the space to share medical knowledge and critique the popular framing of anorexia as a disorder.

Any one of [the active members of the pro-ana forums] could calculate a BMI for you and any one of them could tell exactly what vitamins and minerals you need to survive and how you could avoid certain side effects. I think the Internet has brought the democratization of medical information in a broad sense, and I think that these participants have certainly been taking advantage of that. And they know in a way what they’re dealing with. Obviously this is not to say that people can “manage” their eating disorders or that there are no harmful effects—sometimes the medical advice seems to be wrong or the poster is challenged on it, but they certainly employ a lot of medical language.We actually see that the participants on these sites have a variety of dispositions about their disorders. Some participants are very open saying that this is a disorder and they want to recover from it; others are very assertive in saying they see this as a lifestyle choice, that there’s nothing to recover from, that it’s not a disease. We seem the same participant, the same person, posting along both of these lines, really teasing out the ambivalence…

That is again one of those findings that took time, that sort of came to us later in the process. We were sort of frustrated that it’s not all “pro-ana, pro-ana, pro-ana”! It’s actually some fairly complex feelings and thoughts and analysis being shared out there about eating disorders. If some of the goals our research is to really think about how we can address eating disorders as a social problem, then understanding that we aren’t dealing with a very cut-and-dried [issue]… is very important.

Boero and Pascoe closed by underscoring that there is no one-size-fits-all model of anorexia, nor is there a one-size-fits-all model for preventing and healing disordered eating. Anorexia as a disease does not, in other words, need to be dropped as a medical or media frame, but the public, the media, the medical community, and individuals need a greater appreciation of nuance and competing expectations about acceptable, desirable body types.

I think it is important to think about the population we are studying. We are studying a largely non-clinical population, which is, in part, what makes this study unique. Among eating disorders, most research has been done amongst clinical populations. I think that what it simply means is that you can’t use earlier characterizations of anorexics based on in-patient studies to characterize pro-ana anorexics. You can’t simply graft on one to the other. It’s a lot more complex.

We have a certain understanding of the person who becomes anorexic, but the communities we’ve been studying who engage in these practices (mostly women) were a lot more varied than these characterizations—primarily of clinical populations—would indicate.

Obviously, we are a society that has a fraught relationship around bodies and food. …We [also] live in a society that ends to individualize. We tend to look for eating disorders in individuals or very small groups or we focus in and blame one structure, like the media. Both have been part and parcel of how we’ve thought about anorexia, bulimia, and other eating disorders, and both approaches really miss the larger social context.

Comments