The Arab Spring, Greek riots. Protests in Wisconsin and Indignados in Spain. The Chilean education conflict, rural uprisings in China, and the Occupy Movement. 2011 was a year of social uprisings. As we leave their anniversaries behind, we asked some of the top social movements scholars to reflect on these events and what we can learn from them.

First, we wanted to know what these revolutions, protests and occupations had in common. Is it fair, we asked, to characterize them collectively as a “global uprising”? Our respondents pointed out the similarities between mobilization strategies, but were skeptical about common goals.

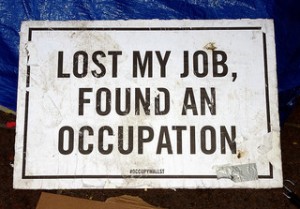

Francesca Polletta: All these actions combined the physical occupation of public spaces with a reliance on virtual strategies and identities. What would the Egyptian Revolution have been without Tahrir Square? What would the Occupy movement have been without the encampment first in Zucotti Park and then in cities as far flung as Sydney, Berlin, and Mexico City? Occupying physical spaces nonviolently, calling for goals of freedom, democracy, and economic equality—these all seem about as 20th century a repertoire of protest as you can get. Yet, the latest in digital media have been vital to the 2011 movements.

Certainly, activists around the globe have taken inspiration and ideas from the uprisings in the Middle East. Activists communicate with each other; they learn from each other; they are emboldened by one another. But it would be a mistake to see a global movement in the making. Global justice activists fought long and hard for just that. But insofar as ordinary people today are conscious of the costs of neoliberalism, it is much more as a result of their experience of how the global financial crisis has rendered precarious their own economic futures than it is of their awareness of what transnational actors like the World Bank or the IMF are doing elsewhere. Nation states are still the name of the game when it comes to much of the policy that matters. I think we will continue to see movements in solidarity with one another but still animated by national identities and targeting national actors.

Michael Kazin: There was clearly an uprising against existing authorities in 2011, but what they had in common is not so clear. In the Maghreb, it was a revolt against authoritarian rulers who had ruled over an economy, which did not deliver the goods to most of their citizens. In the U.S., it was a protest against those at the top (and not really “in charge”) of a financial order that threw the rest of the economy into recession. Democratically elected officials were viewed as abetting “Wall Street,” but the protest didn’t aim to overthrow them. The Wisconsin case is an exception here.

But it is clear that each major uprising helped inspire and, in some instances, even organize later ones. So what happened in Tahrir Square and Madison in February was emulated, at least tactically, by those in the plazas of Madrid, Barcelona, and other Spanish cities in May and June. And some indignados traveled to New York to teach the Occupiers-to-be how to hold “general assemblies” and organize tent encampments. The huge demonstrations in Tel Aviv last summer, unfortunately, don’t seem to have had this same impact—no doubt, because of the dim view most leftists have of Israel and Israelis.

James Jasper: Perhaps the greatest failing of intellectuals is to believe that they are living through a world historical moment, the culmination of this or that Hegelian trend. Some of these protests inspired others, and many were opposed to neoliberalization, but most had distinct roots, especially the Arab Spring and the Chinese protests. I suspect that a global civic culture, like cosmopolitanism, is the dream of a few globe-trotting intellectuals.

Mohammed Bamyeh underlined the common language used by different movements, signaling the birth of a “global culture of protest,” if not a global set of goals.

Bamyeh: One can identify first and foremost the power of example: all these movements are aware of each other, and the latter ones clearly draw inspiration from earlier ones, even though the specific local grievances may not be the same, and even as the nature of the political system confronted by each of these movements differ greatly. To see Arabs as example for anything positive in the contemporary age is itself a remarkable development. But it shows that the perceived essential differences, “clashes of civilization” and so on, have been more than ever discredited as we see the emergence of a new global culture of protest.

Beyond the power of example, one can note some astonishing similarity in slogans. In particular, six common themes define the language of all these movements: first, they see themselves as movements against corruption. The system, whether democratic or not, is regarded increasingly as answerable in the final analysis to special, if not secretive, interests, rather than to a popular will. Second, and related to that, there is the notion that the little person is less and less represented in the system, even in a democracy. Third, there is the notion that the protest addresses the interests of “the people” as a whole, or at least 99% or some super-majority, rather than the interests of a specific class (say the working class). Fourth, these movements seem to be suspicious of parties and organizations in the traditional sense, with a clear preference for loose structures, informal networks and resistance to precise or detailed ideologies, as well as to leaders. Fifth, basic to all these movements is a rejection of the “no alternative” claims of ruling elites, who in recent years have appeared to provide populace with only minor variations on the same basic socio-economic blueprint, thus making democracy itself less meaningful as the arena for the production of genuine alternatives. Finally, there is a certain enticing vagueness as to specific demands. This vagueness, while it may make the movements appear less focused, it also makes them more attractive for the purpose of expressing indignation at the system as a whole. This vagueness is tolerated, it seems, partially because it provides these movements with a sense of experimental youthfulness.

[On the other hand] one should [also] be careful here. It would simply be preposterous to compare the Libyan Revolution, with a death toll of probably 60,000, to anything that happens on Wall Street. The same could be said of Syria, where it took almost a year for an originally peaceful to assume features of armed resistance, after confronting relentless and appalling regime violence. The real risk to their very life taken by protesters in Egypt, Yemen, or Bahrain are not easily comparable to anything we see elsewhere.

After probing for commonalities across locations, we asked after commonalities across history. Did our respondents think social uprisings of 2011 would hold world historical-importance comparable to, say, the student movements of 1968 or the European revolutions of 1848? All were cautious.

Kazin: As any historian will tell you, it’s far too soon to tell.

Jasper: Like Michael, I know better than to make predictions like that.

Polletta: The revolutions in the Arab world will undoubtedly transform those societies, albeit in hard to anticipate ways. At the same time, European anti-austerity demonstrations, the Occupy movement, Chilean education protests, and other protests centered on economic inequality will be seen as expressions of discontent wrought by the global economic crisis. The question, to which I honestly don’t know the answer, is whether the latter mobilizations will also result in substantial government reforms.

Bamyeh agreed that time would tell, but retained hope for the power of creativity inherent in social uprisings.

Bamyeh: If they aren’t, we are in for a long period of hopelessness, which is likely to be expressed in the political culture by increasing demagoguery and symbolic posturing, and in the culture at large by nihilistic tendencies. But there are reasons for optimism. In the final analysis, what provides a movement with a world historical importance is its world historical creativity. This is what makes it referenced by later generations as an influence to be reckoned with, or as a legend even when it had failed. The failure of the Paris Commune in 1871, for example, did not it diminish its significance for revolutionaries throughout the world for generations afterwards, and many of its own reforms were eventually integrated into the French educational system itself. But in that case, what we call “creativity” occasioned what participants felt as their license to alter social and political relations in ways that had been inconceivable from the point of view of their immediate prehistory. Are we at this stage? Do we feel entitled to such a radical license?

While we were on the subject of creativity, we asked about the mobilization techniques that made the protests of 2011 so visible. Polletta and Jasper drew attention to the role of new communication technologies in these movements.

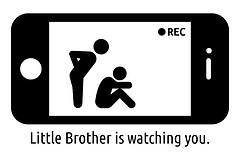

Polletta: Activists are using new media to do old things, like coordinating demonstrations and communicating with allies, but also to do new things. In places with state controlled media, activists have used digital media to breach the state’s censorship and to build support both within and outside the country. In China, a new industry of online news outlets has served as a forum for citizens’ exposes of local corruption. As Christoph Steinhardt shows, local protests have forced party officials to discipline provincial authorities, lest the protests spread to the center. In places with a free press but where protest activities usually fly under the radar of news outfits, activists have used cell phone footage of police brutalizing protesters to gain national and international attention for their cause. Interestingly, mainstream media have been eager disseminators of citizen-generated news.

Jasper: The media have made a lot of Facebook’s role in Egypt and elsewhere. It seems the latest in a long series of steps that have made communication, and thus mobilization, easier. But opponents usually find ways to counter every innovation, such as shutting down the phone network. The strategic initiative goes back and forth.

Polletta: One thing I learned is that, in some ways, virtual collective identity—the kind created online—may be more effective in mobilizing than the collective identity forged in church basements and college dorm lounges by people holding hands and singing “We Shall Overcome.” We tend to assume that people develop a stronger bond when they see, hear, and feel one another. Yet, social psychological research has shown that when it comes to some identities, such as nationality, people are more likely to feel a common bond with people they can’t see. Why? Because the less anonymous the people with whom they you are interacting, the more likely you are to be distracted by other things about them, things that make them not like you. So a collective identify forged online may be mobilizing precisely insofar is it is virtual, and therefore partial and even ambiguous. Digital media may make possible an imagined community that is in some ways closer to what supporters want it to be than what it really is.

But for Bamyeh, the highlight of last year’s tactics was the almost old-fashioned occupation of public space, as this tactic offers both time and space for participation and deliberation.

Bamyeh: Clearly important are the loose structures, the role of social networks, and declining role of parties, old organizations, and leaders.

Occupying public places for an extended and sometimes indefinite period has become symbolically significant, and there appears to be less stress on marches and demonstrations. The occupation tactic gives you a more conversational revolution, one whose aims are discovered in the debating process itself rather than arrived at beforehand. Ordinary participants learn in this case what the revolution should be about, and a range of new concepts quickly become relevant in the street: without prior schooling, for example, one may learn about liberalism, socialism, representation, or more significantly, how such abstractions may be interpreted in terms of one’s own life history and social experience.

For his part, Kazin emphasized continuity over rupture or innovation:

Kazin: Obviously, the uprisings of 2011 used “social” cybermedia more than any previous, comparable insurgencies. But I am not (yet) convinced that such forms of communication have rendered obsolete what Charles Tilly called the “repertoire” of protest initiated two centuries ago. Big street demonstrations, stirring rhetoric (even if transmitted via mobile phone), and demands agreed to by assemblies of activists—these go back to the beginnings of modern social movements and continue to be necessary for mobilizing large numbers of people today.

As academics work furiously to write papers and commentary on the protests, we wondered how social scientists hoped to meet the challenge of interpretation. Jasper contended that the protests confirmed and advanced theory production “already under way.”

Jasper: Scholars have mostly responded emotionally. These protests make us feel good, excited, and optimistic. If they advance our theories, I would guess that it will be by encouraging trends already under way: more focus on individuals, such as Bouazizi; better understanding of how violent repression can sometimes stimulate protest rather than always dampening it; and generally more attention to the micro-level mechanisms (emotions, decisions, interactions) that comprise politics.

Bamyeh saw a bigger challenge to theory production, especially in its capacity to account for the spontaneous and the unexpected:

Bamyeh: In the middle of the revolution in Cairo, I felt that a lot of social science was anti-human, driven by an impulse to substitute all humanity with mechanical models that stand in for it. The problem is that much of social science is dominated by an orientation to structures and determinations, and sees no point in exploring dimensions of human creativity and agency that cannot be easily contained in such structures. It sees no humans facing complex choices and experimenting with creative spontaneous solutions. But it is precisely these dimensions of creativity that give us the greatest movements in history, producing innovation precisely where it was least expected. The best social science, I think, is one that enjoys surprises, including failures of prediction. So I learned to appreciate the complexity of ordinary humans, and now find it imperative to describe as best as I could the details of this story, and in doing so think about it at both the micro and macro levels simultaneously, without privileging one or the other, and explore local and global facets, again without assuming that one is more important than the other.

I do not think that we should be too quick to theorize about these movements without paying attention to what they actually say, nor assume that we can just easily “translate” their common slogans into some abstraction that we like them to be against. Rather, theorizing should focus on taking seriously the concrete distress and felt insults that move people into the streets by the millions.

Our roundtable would not be complete without asking for predictions about the future, including prospects for the protests and suppression of dissent. Jasper emphasized how new technologies and techniques empower both the protestors and the police.

Jasper: American police have learned techniques for corralling participants into uncomfortable spots, but these have not spread globally. On the other hand, protestors have learned to videotape unpleasant encounters with the police. The more of these you make, the more likely you are to capture an instance that will make the news—the best example being the University of California Davis policeman pepper spraying protestors.

Kazin maintained that the “fate” of the protests still depended on national power structures.

Kazin: Despite all the talk about a globalized market, media, and politics, the fate of each of these uprisings depends, and is likely to continue to depend, on the particularities of the political culture and history of each nation-state in which a particular uprising occurred. Compare, for example, the democratic triumph of Islamist parties in Egypt with the fragmentation of the Occupy movement in the United States (and, perhaps, in Britain too). The Islamists worked for decades under dictatorship to prepare for their day in the sun; but most Occupiers were fairly new to activism, and they live in a nation with a long, uninterrupted history of democratic elections, however cynical they might be about the limits of the policies that elected officials enact.

While Polletta remarked that suppression could travel as much as protest does, Bamyeh closed by reminding us of the possibility of co-optation.

Polletta: All the things that students of revolution have seen as important in accounting for revolutionary trajectories—the configuration and strength of opposition groups, who controls the military, the independence of the judiciary, the role of foreign allies—surely will play a role in how the uprisings play out in those countries. More generally, we know that challengers’ innovations are studied and responded to by authorities in a kind of battle of tactical innovation. Today we see authorities in one country responding to events in other countries, trying to prevent the spread of revolutionary fervor. The Chinese government imprisoned scores of activists and shut down Internet access. Zimbabwe arrested six activists for watching video footage of the Arab protests. The Russian media bombarded its citizenry with messages about the chaos created by the Arab revolts—with the clear implication that anti-Putin protests in Russia would wreak the same havoc. Activists in Israel and Iran were suppressed. The result, according to the most recent Freedom House report, is that by the end of 2011 more countries registered declines in political liberties than the year before. Are these the defensive reactions of authoritarian regimes in jeopardy? Or do they signal further repression? It’s unclear. I’m also wary of calling this an organized global reaction to the global uprising. Just as protesters in Boston drew inspiration and ideas from protesters in Madrid, Santiago, and Cairo, so authorities are undoubtedly paying attention to what works and what doesn’t in quelling protest in other cities and countries.

Bamyeh: It is to be expected that ruling interests seek whenever they can to co-opt revolutions and all protest movements. In those Arab countries where the revolutionary situation was less developed, we saw the beginning of unprecedented (though hardly radical) reform process from the top. In the U.S., the Occupy Movement’s general aims are claimed as well by various prominent politicians. Yet, there is not yet a vigorous global counter-revolution or counter-reaction, except perhaps in the case of Russia, whose government has sought to undermine the Arab spring and where there is a real battle concerning the future of Putin and, along with him, the Russian experiment with democracy as a whole. Elsewhere governments face the problem of dealing with either a widespread perception of a deep-seated politico-economic corruption, as in the U.S., or absence of choice about austerity and related policies, as in Europe, and the insufficiently representative nature of political systems nearly everywhere. The latter will only become more acute given the global and thus impersonal nature of various large crises, which could only be tolerated if we have a global democracy. But we do not. So if these protests finally encourage us to reflect seriously on the most glaring absence in the world, namely the absence of a global democracy, then they would have already ushered in a world-historical project.

Sinan Erensu, Kyle Green, Sarah Lageson, and Stephen Suh are sociology graduate students at the University of Minnesota. They are all members of The Society Pages’ graduate editorial board.

For further information, our readers might turn to the interdisciplinary website Mobilizing Ideas, based in the The Center for the Study of Social Movements at the University of Notre Dame.

Comments