On this historic day, the US Supreme Court’s ruling on health care is being hailed as “a victory for all Americans” – but will all Americans benefit equally from the new health care law signed into law by President Barack Obama? No, not those, like Obama, who are male.

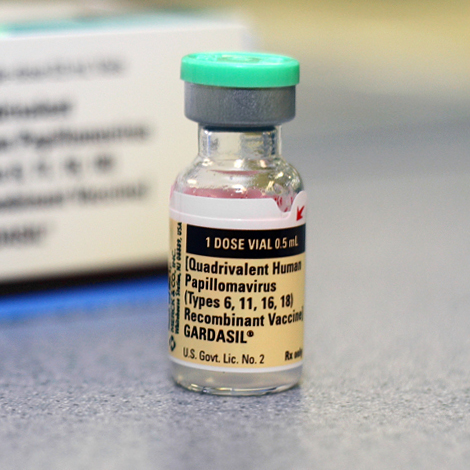

The ACA’s list of “Covered Preventive Services for Adults” includes screenings for only two sexually transmitted infections (STIs): “HIV screening for all adults at higher risk” and “Syphilis screening for all adults at higher risk.” They do include “Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI) prevention counseling for adults at higher risk,” and “Immunization” for the STIs Hepatitis B, Herpes and Human Papillomavirus (HPV). All sexually active boys and men are potentially at risk for contracting a wide range of STIs, including HIV: the interpretation of “higher risk” could keep many from receiving necessary care.

If you scroll down this page, you’ll find the longer list of “Covered Preventive Services for Women” which includes additional sexual and reproductive health care screenings related to breast cancer, cervical cancer, chlamydia, contraception, gonorrhea, plus extra screenings HIV and HPV. This laudable list is capped off by “Well-woman visits” described as, “preventive care visit annually for adult women to obtain the recommended preventive services that are age and developmentally appropriate….” Why would a man not benefit from these types of services?

A google search for “well-man visits” turns up nothing on U.S. government websites and only one company’s description of their “Well Man Examination” policy: it includes only “Digital rectal exam; and Screening PSA test (age 40 or older).” Younger men could benefit from an examination for testicular cancer, “the most common cancer in American males between the ages of 15 and 34.” None of these tests are mandated under the ACA.

Looking again at government resources, the inequity jarring. In addition to having a website devoted to National Women’s Health Week in May, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services also sponsors an Office on Women’s Health website. If you’re on the homepage of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and search for “men’s health” you will not find a men’s health website. However, their Office on Women’s Health website (somewhat ironically) features the U.S. government’s only resource webpage for men’s health, including a link to men’s sexual health. On this page, it focuses more on aging and sexual dysfunction, with only one small link to sexually transmitted infections. This “sexual health” page seems to patronize and condescend to men, doubting their abilities to care about and seek sexual health care:

“Sexual health is a source of concern for many men. Yet some men are not comfortable talking to their doctors about sex.” And, later on, “Remember that problems with sexual health are medical problems, and your doctor can help.”

If you live in King County, WA, then you might be in luck: their Public Health website features a fairly detailed description of “physical examinations for men.” If you don’t feel comfortable seeking these examinations from your regular doctor, then check out Planned Parenthood: a national organization that provides men’s sexual health exams. While I’m not sure how many U.S. teen boys and men would think of Planned Parenthood clinics as their home base for sexual health care, U.S. health policymakers should look to them for guidance. Depending on the specific PP clinic, their services might include:

- checkups for reproductive or sexual health problems

- colon cancer screening

- erectile dysfunction services, including education, exams, treatment, and referral

- jock itch exam and treatment

- male infertility screening and referral

- premature ejaculation services, including education, exams, treatment, and referral

- routine physical exams

- testicular cancer screenings

- prostate cancer screenings

- urinary tract infections testing and treatment

- vasectomy

U.S. men, where is your outrage? Where are the protests demanding equality in sexual and reproductive health services? Why is there no U.S. Office on Men’s Health? A little digging online unearthed the failed “Men’s Health Act of 2001” which articulated the need for an Office of Men’s Health. If this act is not a priority for today’s politicians, then I encourage you to do your part to raise awareness about the need for accessible, affordable and comprehensive men’s sexual and reproductive health care. All of us — men, women and children — will benefit from better men’s sexual health.

There’s

There’s